Hatey?

« previous post | next post »

Because of the awful disaster in Haiti, that country's name has been in the news, and this prompted reader RH to wonder about its English pronunciation.

I am currently watching the CNN coverage of the earthquake in Haiti, and without exception the name of the country is pronounced "hatey". Surely "Hayiti", or even "Ayiti" would be better, and just as easy for the reporters to learn?

In IPA, the observation would be that American English speakers generally say [ˈɦeɪ.ɾi], whereas a closer imitation of French (or Haitian) pronunciation would be something like [ɐ.iˈti].

But the conventional English version of foreign names is often — even usually — quite far away from the native's version. Italy is not very close to the way that Italians pronounce Italia; Russia is similarly distant, in stress pattern and vowel quality, from Россия; and in cases like Germany for Deutschland or Finland for Suomi, there isn't even a morphological connection.

In fact, there are relatively few countries whose conventional English name is the closest possible English approximation to the native pronunciation. (And this is complicated by the existence of many countries with more than one official language, and thus more than one official name, like die Schweiz / la Suisse / la Svizzera / la Svizra, none of which are optimally approximated phonologically by "Switzerland".)

I haven't been able to determine when the current English pronunciation of Haiti became conventionalized, but I imagine that it goes back as far as the name does. I guess that this would be the early 19th century — the name was adopted in 1804 at the time Haitian independence from France, from "one of the indigenous Taino names for the island".

[While you're thinking about it, why not donate generously to Haitian disaster relief? Some information for Americans about how to do this can be found here. For example, if you text "HAITI" to 90999, a donation of $10 will go to the Red Cross for relief efforts, charged to your cell phone bill. I'm sure that the rest of you can easily find your local alternatives.]

Peter Taylor said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:11 am

Oxford gives ˈheɪti.

bulbul said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:12 am

and in cases like Germany for Deutschland or Finland for Suomi, there isn't even a morphological connection.

Yes, but there is a historical one – some names of countries, like "Germany", "Lithuania" or "Norway", were not adopted from names used in languages spoken in those countries, but rather from Latin. Same goes probably for Finland, although there it was the Swedish name rather than the Finnish one that is the ultimate source. Couldn't Haiti have been brought to English via the same route?

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:20 am

It's understandable why foreign (to Americans) names would not necessarily be pronounced the way the locals do, but that's true even of names within the US that have idiosyncratic pronunciations. In my home state of Georgia, the area around the town of Vidalia produces well-known onions, but few outside of Georgia pronounce the name the way the locals do. It's the same way with Vienna, Ga, in which the locals give the "i" and the "e" a longish sound. I also suspect that many Americans who do not live in or near Nevada pronounce that state differently from people who live there. An Indian student I knew at Georgia Tech pronounced Georgia something like "Jaw-jaw." He said it was so he could remember how the locals said it.

kip said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:30 am

@Mark P: Another one, here in Concord, NC, it is pronounced "con cord" (rhymes with "board"). But non-locals usually pronounce it like "conquered", the way they say it in Concord, NH and Concord, MA (and presumably any other Concords in the nation).

Edith Maxwell said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:36 am

Mark P: Now you must tell us how Vidalia natives pronounce it!

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:45 am

@Edith Maxwell: Unfortunately I am not familiar with the way linguists define pronunciations unambiguously, so I can only give a rough guide. Vidalia natives make the first "i" and "a" long, and the accent is on the second syllable. There is what I would say is a secondary emphasis on the first syllable. Once they are done pronouncing the first two syllables, they are so tired that the rest of the name sort of trails off until they get to "onions."

[(myl) The usual outsiders' pronunciation would be [vɪˈdeɪl.jə], I think — that's how I would say it, anyhow. If I understand what Mark P. is saying, the main difference for the locals is that the first syllable has a secondary stress and an associated vowel shift, so that it's pronunced like the word vie. I believe taht the local pronunciation of the vowel in the lexical set involving vie, pie, my, etc., would not have the high front offglide that we northerners would use, so the first syllable would become something like [ˌvɐ]. The nucleus of the second syllable might be somewhat lower and more central as well… but at this point I'm speculating well beyond my knowledge of this locality, so I'll see if I can get an opinion from Bill Kretzschmar, who may very well be able to provide us with an audio clip from the place itself.]

John said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:49 am

We shouldn't confuse regional accents or unusual/unexpected local pronunciations with country names in various languages/cultures. The capital of SD is pronounced "Peer" in the upper mid-west, but we in the NE don't call it "Dakota City" vel sim.

Some names are clearly anglicized pronunciations (France), some are anglicized spellings (Italy), some are historically frozen (Florence, which is), some are historically based, but applied independently of what the country is called internally (Germany, also anglicized), and surely there are other types as well.

William Safire had an article on this some years back, in which he argued that we shouldn't go around changing the English name of a country, just because the people who live there have changed it. His example was Burma/Myanmar, IIRC, and obviously there are some political aspects to that as well. (Ah, here it is: http://www.nytimes.com/1989/10/22/magazine/on-language-bring-back-upper-volta.html )

My favorite recent example is Ivory Coast, which I have been told to call Côte d'Ivoire, which seems to me an absurdity.

[(myl) There's some discussion of Burma/Myanmar here; and of Persian/Farsi here.]

language hat said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:12 am

I find this idea that English-speakers should approximate the pronunciations of other languages tiresome and invidious. Geographical names are words like any other; they are part of the language and conform to its rules and habits, and there is no reason to change them because someone thinks it's insulting to French-speakers not to pronounce a French name à la française. If Ah-ee-TEE, why not Pah-REE? With a uvular r?

And yes, the idea of bowing to the wishes of a murderous ruling junta and calling Burma "Myanmar" at their behest is repugnant.

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:18 am

@John said: There are two cases, as you say. In one case, the English name is different, not just pronounced differently. But the other case is more relevant to Haiti. In that case, American English speakers simply pronounce the name the way it would commonly be pronounced if it were an English name. That is the case both for Vidalia and for Haiti.

davek said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:49 am

I'm intrigued by the case of Holland, which as I'm sure everyone knows is a province of the Netherlands, not the name of the whole country. And the language they speak is Dutch, which derives from the name of a dialect spoken in parts of the region in Medieval times.

J. W. Brewer said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:53 am

In 19th century English-language texts, the name of the country seems to have been commonly (not confident whether 50%+ of the time) spelled "Hayti," which seems further confirmation of the usual AmE pronunciation, at least as to the first syllable. There are apparently various places around the U.S. named Hayti, some of which are mentioned at the wikipedia disambiguation page. However, wikipedia claims that Hayti, Missouri is pronounced "hay-tie," which is presumably intended to be distinct from "hay-tee."

If "Haiti" were really an indigenous English name would its spelling really have been standardized with the -aiti spelling, or even -ayti, as opposed to by analogy to either "matey" or "Katie"? Or "Katy" for that matter. I think the spelling itself suggests foreignness and thus to some degree signals the possibility of a non-intuitive pronunciation. Put another way, the intuitive pronunciation is not obvious because of the departure from usual spelling conventions. What's the basis for an intuition that the final "i" is more likely to be like "Brandi" or "Suzi" (both non-standard spellings, fwiw) than like "Jedi" or "Lodi"? That's apparently not the intuition (see above) they have in Mo.

Marion Crane said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:58 am

This is a fun topic, but muddled, since there are so many ways in which country names have originated, especially if you consider not just English but other languages as well. Using examples already mentioned, Haiti, Burma, and Ivory Coast:

Haiti we just pronounce the way we would had it been a Dutch word, coming close to RH's first suggestions. And why not? It's a different language, with different rules on pronounciation. How would a random Dutchman know how Haitians pronounce the name of their own country? You just go by what you know. Especially if the country's language has sounds your own language does not possess. (I certainly don't demand from anyone who speaks English to be able to pronounce 'ij' or 'ei' correctly.)

As for Burma and Ivory Coast, we're even moving away from pronounciation and into cultural and historical trends vs recent political movements.

Burma we write Birma, by the way, but it's obviously pronounced similarly and probably borrowed from the English name anyway. Officially we're supposed to call it Myanmar as well, but personally I keep forgetting. I know what is meant by Birma; I have to do a mental backflip when I see or hear Myanmar.

Ivory Coast is Ivoorkust, basically a literal translation into Dutch. The request to use Cote d'Ivoire instead has pretty much fallen on deaf ears, over here.

The thing is, I don't see Germany pleading for Deutschland in international use any time soon, because everyone's used to it. Likewise I don't care if foreigners say the Netherlands, Holland or Les Pays Bas (as long as they don't confuse us with Denmark, please). Burma, however, has the whole colonial history that probably gives the English name a bad taste to the natives, so I see why they would want to get rid of it – it was forced upon them in the first place.

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:59 am

@MYL: I think you are pretty much right on the Vidalia pronunciation (if I understand what you're saying). I think you have the first "i" right; the long i is a southern long i, not a northern long i. I used Vidalia as an example because I have heard the name used on network television a number of times in reference to the Vidalia onion. On one occasion (maybe the Today Show) even with some coaching from a local, they never got it quite right.

Ben said,

January 14, 2010 @ 12:00 pm

I've been struck by the pronunciation (on NPR and BBC radio) of 'Port-au-Prince', with 'Prince' being pronounced straightforwardly like the English word 'prince' for royalty. I think 'Port-au-Prince' might be pronounced differently (in English) in Canada or at least in French-speaking parts of Canada. There's an asymmetry here with the French pronunciation of the name of the artist who was, and perhaps still is, known as 'Prince': it's pronounced more like the English 'prince' for royalty than like the French 'prince' for royalty. (I suck at phonetics. I won't even try to describe these pronunciations. Sorry.)

mollymooly said,

January 14, 2010 @ 12:03 pm

Wells' LPD gives /ˈheɪ ti/ first, but also /ˈhaɪ ti/, /haɪ ˈiː ti/, and /hɑː ˈiː ti/

French "aï" is often an approximation to English /aɪ/; running in reverse, "Haïti" would be /haɪti/, rhyming with "nightie".

The closest analogue to "Haïti" I can think of is "Zaïre", which rhymes with "spy ear" for me, and "spa ear" for others.

I think when a previously unfamiliar foreign name comes to the notice of anglophones, they make their best effort at approximating it, which may be close or not. Once it is recognised as to some extent an English word, its pronunciation will evolve in the manner of all English words. Meanwhile, the native pronunciation will be evolving differently. The fact that more recently recognised names are closer in English to the original than those imported centuries ago is thus natural, and not a moral reflection for good or ill on today's or yesterday's speakers.

Having said which, Lippincott's pronouncing gazetteer of 1856 gives /ˈheɪti/ for English and /(h)ɐ.iˈti/ for French. What were the 19th-&18th- Century French&creole pronunciations?

mollymooly said,

January 14, 2010 @ 12:19 pm

There is the converse example of "Ireland", which you can get away with calling "Republic of Ireland", but must never call "Éire" in English.

Lane said,

January 14, 2010 @ 12:40 pm

I think the first syllable in "Vidalia" would vary a bit by class in the south. To put it bluntly, a redneck (my father's family's native dialect) would say "vie"-dalia, with a glide. A more upper-class southerner would be more likely to say "vah"-dalia. Just my instincts here, but I do come from Etlanna, Jawja.

Chris said,

January 14, 2010 @ 12:49 pm

The tendency to Anglicize foreign names is an old one. I've been told that in the mid-16th century, when England still had a toehold in what is now France, Calais was routinely referred to by the English as "Callus" and Le Havre was "Newhaven."

[(myl) An elderly British friend, who had been raised by a French governess and was essentially bilingual in English and French, once offered me (in English) what I heard as "a little dew bunny". It took me a few seconds to realize that he was offering the aperitif Dubonnet. This style of extreme anglicization of French words when speaking English was apparently typical of Englishmen of his class and generation, even those with an excellent command of French.]

Coby Lubliner said,

January 14, 2010 @ 1:00 pm

Visalia (California) is pronounced /vɪˈseɪljə/ according to Wikipedia, though I've also heard /vaɪˈseɪljə/. How is Visalia (Kentucky) pronounced? Both town names are supposedly derived from that of a family named Vise, presumably pronounded /vaɪs/.

Stephen Jones said,

January 14, 2010 @ 1:13 pm

My view is that if the different name of the country is one that the English used because they couldn't or couldn't be 'arsed to use the native name (Seville, Florence, and Cairo spring to mind) then we should accept it.

But where the English name was one that colonialists enforced as an official name (as is the case with Bombay or Madras) then we should accept and use the new official name the government decides to give it.

Stephen Seidman said,

January 14, 2010 @ 1:14 pm

Naming places and countries in other languages is a confusing topic. History and phonology come into play in different ways. Here are a few examples:

The German names for the Baltic states are Litauen (Lithuania) and Lettland (Latvia). Different patterns are used for countries in the same region.

Spanish phonology frowns on initial consonant clusters beginning with 's'; hence "Escocia" for Scotland.

In Italian, "Paris" becomes "Parigi"; at least it gets the final vowel correctly. Do other European languages indicate that the final 's' in Paris is not pronounced? Both German and Spanish pronounce the 's'.

Jackie said,

January 14, 2010 @ 1:17 pm

When I was young (I'm 67) Haiti was not pronounced Haytee in the UK; Each vowel was pronounced separately. So the change is more recent than the 19th century. I was interested this evening to hear Gordon Brown pronounce the vowels separately at the beginning of his announcement on aid for "Ha-iti", but his next mention of the name was with the modern pronounciation Haytee.

I notice how the French in particular always pronounce foreign names as they would be pronounced if they were French. For example Handel has no H in France and Mozart is Moh-zzar without the German ts pronounciation in the middle and without the t at the end. The English manage to pronounce the name as it would be pronounced in Germany just as we manage to say Bate-hoven rather than beet as in beetroot.

Sven said,

January 14, 2010 @ 1:32 pm

I think there is a little overgeneralization in this thread, and that conventions for anglicizing foreign proper nouns vary by the type of entity denoted by the noun. On one end of the spectrum are country names, which have been consistently anglicized, while on the other end are names of persons, where it is normally consider polite to ask them how they pronounce their own name and try to replicate it as close as possible. (Closeness is not always possible, as few native English speakers can pronounce "van Gogh" or "Brkljačić".)

I find the nuances of these conventions (and exceptions from them) quite interesting, both within a language and across languages: different cultures have quite different approaches to pronunciation of foreign names.

Mr Fnortner said,

January 14, 2010 @ 2:34 pm

Mark P and Lane, vie-DALE-yuh is a close to the pronunciation as I can come. Just don't make too much of the L as you say it (like, keep your tongue off the roof of your mouth) and you'll be OK. For a real southern accent, the vie part could be closer to vah. But if you strain, you'll sound affected or fake.

Simon Cauchi said,

January 14, 2010 @ 2:35 pm

@Chris: "I've been told that in the mid-16th century, when England still had a toehold in what is now France, Calais was routinely referred to by the English as "Callus" and Le Havre was "Newhaven."

I've seen Calais rendered in 16th-cent. English as "Callice". Also Montreuil as "Muttrell", Bordeaux as "Burdells", Montpellier as "Montpelleer", and Pavia as "Pavy".

Simon Cauchi said,

January 14, 2010 @ 2:38 pm

And I shocked my English sister when I once pronounced "Renault" in the New Zealand manner, with the stress on the first syllable and all the consonants sounded.

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 2:59 pm

Mr Fortner, if I read you correctly, that is pretty close to the way I know it. Pronunciation of the southern "i" is not uniform, even within Georgia. In some places it is close to "ah" but that's not true in all parts of the state, including my home in northwest Georgia. I'm afraid we have a flat, fairly unattractive accent.

The type of southern accent you mention, which I believe is less rhotic than where I live, seemed to be more common in southeast Georgia, somewhat south of where I used to work in Augusta. My work often took me into the boondocks south of Augusta, and I noticed a distinct difference in accent there. Vidalia is south of Augusta, so the natives may well pronounce the long "i" closer to "ah."

Mark P said,

January 14, 2010 @ 2:59 pm

Sorry – "Mr Fnortner"

Alan Gunn said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:05 pm

We lawyers have a similar issue about pronouncing Latin and Law French terms. Traditionally, we pronounced them as if they were English words, with a few exceptions ("Cy Pres" was pronounced as if it were "sigh pray," which Frenchifies the "Pres" but not the "Cy." So, for example, we'd pronounce the last word in "pro hac vice" just like the English word "vice." Over the last twenty years or so, though, I've heard a lot of lawyers trying to pronounce these terms as they think Latin would have been pronounced (does anyone really know?). That this tendency has accompanied or perhaps followed a decline in the number of people actually taking Latin in school seems odd.

Chris said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:05 pm

In the case of Germany vs. Deutschland, the difference actually comes from Proto-Indoeuropean and Proto-German. In German, the group of people that originally split and formed many of the peoples of modern-day Europe were called the "Germanen" and were referred to that way until the Franks and other tribes split off. It was much later that the "Germanen" (which had subsequently moved into modern-day Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Poland) began calling themselves "Deutsch." Thus, the origin of English's "Germany" is simply that English never evolved to reflect the change in the way early German people's addressed each other and their own country.

Nathan Myers said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:15 pm

My favorite is "Leg-horn" for Livorno. I fantasize a historical gutteral "gh", but wonder the true derivation.

[(myl) The OED says, mysteriously,

[Use of the place-name Leghorn, ad. It. Legorno (16-17th c.), now replaced by Livorno, repr. the classical L. name Liburnus.]

No explanation, so far, of where the /g/ came from, nor why it went away in Italian, nor whether the 'h' was just a quirk of spelling or part of a folk etymology.]

Richard said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:18 pm

Ben: I was also struck by the way Port-au-Prince is pronounced. One of the CNN weathermen, whose name was Guillermo (I guess that's a big hint) used the French pronounciation, but still went with "Hatey" for the country name. And interestingly everyone gets "oh" for the "-au-" in the city name.

James said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:28 pm

Like Jackie, I distinctly remember always hearing 'Haiti' pronounced with three syllables here in Britain – and I'm in my twenties, so it can't be a longstanding shift. In fact, I was taken aback for a moment when I heard the 'anglicized version' on the BBC this morning. I'd only ever heard Americans say it that way before.

Simon Cauchi said,

January 14, 2010 @ 3:41 pm

@Jackie: Handel is properly Händel, and is so pronounced by Germans. As I heard when watching a TV programme about him.

Jesse Tseng said,

January 14, 2010 @ 4:25 pm

Ben@12:00 pm, Richard@3:18 pm:

Are people saying "Port-au-Prince" with or without the [t]? (And no, I don't mean the [t] in [pɹɪnʦ].)

Richard said,

January 14, 2010 @ 4:26 pm

Jesse: with

Mr Punch said,

January 14, 2010 @ 4:43 pm

The strangest case, to me, is that the Canadian province known as "Nova Scotia" in English (!) is "Nouvelle Ecosse" in French.

Also, aren't Myanmar/Burma and Mumbai/Bombay, etc., basically pronunciation or transliteration issues? That is, aren't the latter names English takes on the former ones, rather than different names?

[(myl) Yes. See here for details wrt Burma.]

David Eddyshaw said,

January 14, 2010 @ 4:43 pm

@Alan Gunn:

In fact a great deal is known about how Latin was actually pronounced:

"Vox Latina: A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin" W Sidney Allen

is a good guide to what we know and how we come to know it.

The traditional pronunciation of Latin in English ultimately goes back to before the changes in English which made our spelling so interestingly different from the pronunciation; in a nutshell, Latin as spoken by English speakers underwent the same sound shifts as were affecting contemporary English. It often works out nowadays the same as pronouncing the words as if they were English, but actually has a tradition of its own (which Allen's book also goes into.)

Mark F said,

January 14, 2010 @ 4:57 pm

Mark P's comment that the first 'i' in Vidalia is a "southern long I" raises the question in my mind of what it means for two pronunciations to be the same. Assuming you want to pronounce it "the way the natives do", do you want to do it phonemically or phonetically? My vote is for phonemically, so that you'd be saying it "right" as long as you're using whatever counts as a "long i" in your dialect.

Ed said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:00 pm

Almost as good as the Leghorn example is the city of Buffalo, which apparently is how the later English speaking settlers understood the name, Beau Fleuve, which was given to it by French explorers. Contrawise, there are many French named places in the American Midwest which have retained their original spellings but have been given unusual pronounciations by the people who now live there.

Russell said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:06 pm

I remember reading that one difference between North and South Korean (could just be prescriptive or present in dictionaries, etc, not on the ground) is in names of countries. South Korean names tend to follow English, while North Korean tends to be closer to the native term. E.g., SK meksikho vs NK mehikho for Mexico. Wikipedia seems to corroborate this, but I think Sohn's grammar (Cambridge U Press) mentions this as well, but I haven't seen mention of how many items differ in this way.

Cameron said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:13 pm

Mumbai/Bombay isn't just a transliteration issue. Nor is Bombay a name imposed by British colonizers. Bombay was (and remains) a transliteration of the name of the city as spoken in Hindi/Urdu. Mumbai is a transliteration of the name of the city in the Marathi language. The powers that be in Maharashtra demanded that the city's English name be changed to match the pronunciation in the official language of that state.

Marion Crane said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:28 pm

@davek: Actually, there is no province called Holland, not any more. Since 1840 it's been divided into Zuid-Holland and Noord-Holland.

But yeah, to refer to the Netherlands as Holland does stem from the time when Holland was still a whole province, and that was a time when that province was pretty internationally active, in politics and trade, and so the part came to be known as a name for the whole (the Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden, which wasn't precisely the same as the Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, but close enough on a global scale).

Most Dutchmen don't really object to the name Holland (though Hollanders as a name for our people is considered slightly derogatory).

The UK has the same phenomenon, of course.

The explanation for Dutch probably follows along the lines of Chris's explanation of Germany – the dialect was Diets, but we stopped using that word for our language and use Nederlands instead, but English hung on to their version of the old term.

Joe Fineman said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:30 pm

Some other whimsies:

Our name "Milan" for the city called "Milano" by its inhabitants is always (AFAIK) stressed on the second syllable, but that must represent a shift, because in _The Tempest_ the meter consistently requires MILan. Why did we change it? To make it sound a little bit foreign, short of calling it Milano?

Likewise, a lot of English-speakers pronounce the third syllable of "Copenhagen" like "hah" instead of "hay". That does not make it anything like the Danish (which would be a trial for most of us), but it does happen to be a fair approximation to the German name — which (I have been told) Danes of a certain age would rather not be reminded of.

George Amis said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:41 pm

@Joe Fineman and others

Milan, NH is pronounced MY-lan. Calais, ME is Callus. Both presumably reflect the older BE pronunciations. (My impression is that the French Calais is now, at least by some classes of BE speakers, pronounced Cally with the stress on the first syllable. A bit like dew bunny for Dubonnet, I suppose.)

Hades or Bust « Trung Chatter said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:49 pm

[…] a germane posting on the Language Log, "conventional English version of foreign names is often — even usually […]

Alan Gunn said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:57 pm

A nice local pronunciation: The Purgatoire River in Colorado was once called the "Picketwire" by the locals, who could hardly have been expected to pronounce it the way the explorers who named it did. Whether this is still the case, I don't know. The river (both spelled and called "Picketwire") features in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence," though it has been moved south to a place where cactus grows. Bret Favre doesn't pronounce his last name like his ancestors in France did either, and who can blame him?

H.L. Menken points out in "The American Language" that the name of my former employer, a university that used to play big-time football, is pronounced "Noter Dame," unlike the Cathedral in Paris.

Coby Lubliner said,

January 14, 2010 @ 5:58 pm

Is "Milan" stressed on the second syllable by Britons? How about the pronunciation of AC Milan (/'milan/ in Italian)? I'll have to listen carefully to the pronunciation by British sportscasters in the upcoming Champions League playoffs.

Ginger Yellow said,

January 14, 2010 @ 6:09 pm

For a long time I thought Haiti was pronounced "hay-shee" in English. No idea why I thought that, but it's not a word you hear spoken much in the UK. I was only disabused of this notion when watching The PJs, which features a character called The Haiti Lady.

"Is "Milan" stressed on the second syllable by Britons?

Yes.

Coby Lubliner said,

January 14, 2010 @ 6:09 pm

By the way, the English names of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Moscow, Warsaw and other places in Northern Europe are probably based on Low German, the official language of the Hanseatic League, which in the Middle Ages controlled most of the region's commerce.

Skullturf Q. Beavispants said,

January 14, 2010 @ 6:33 pm

Mark F's question at 4:57 pm is a great one. My vote is for phonemically as well.

In other words, when I as a Canadian want to know how to correctly pronounce Wokingham or Cairns, I'm not required to mimic the accent of somebody from southeastern England or Queensland — it should suffice to answer questions like "is that the vowel from 'poke'" or "is that the vowel from 'fair'"?

Adrian Bailey (UK) said,

January 14, 2010 @ 6:52 pm

I've always pronounced Haiti as three syllables, and I'm not sure I'm going to change to two just because the BBC has changed its policy.

2. I notice that whilst Britain is quite quick to adopt name-changes requested by other nations, some other countries ignore them. I hope Hungarians don't stop using the word Elefántcsontpart. :)

Ben said,

January 14, 2010 @ 8:25 pm

The question about 'Milan' reminds me of the question of what to call the city that hosted the 2006 winter games.

Rolig said,

January 14, 2010 @ 8:32 pm

Checking the Russian Wikipedia page, I see that the Country Formerly Known As Ivory Coast is no longer called in Russian Берег Слоновой Кости (Bereg Slonovoy Kosti, or literally, "Coast of the Elephant Bone", i.e. "Ivory Coast"), but is now officially Кот–д'Ивуар, which transliterates as Kot–d'Ivuar. Not only has the name become opaque to Russians who do not speak French (the great majority), but the country appears to have become a tomcat (the usual meaning of "кот") named d'Ivuar.

Coby Lubliner said,

January 14, 2010 @ 8:41 pm

Italians who speak English, in my experience, say Turin, Venice, Rome etc., just as English-speaking Mexicans (but not Chicanos!) usually say Meksiko and not Mehiko, French people say Marseilles (with the final z sound), and so on. That is, people all over the world seem to respect the fact that the names of their countries and cities are not called the same as in their own language. In the course of the radio and TV coverage of the Haitian earthquake I have heard English-speaking Haitians generally say "hatey" and Port-au-Prince with the English pronunciation of "prince". The only ones that I've heard say Port-au-Prance have been Canadian radio journalists.

Terry Collmann said,

January 14, 2010 @ 8:45 pm

Chris: but "Dutch" in English meant what we would call "German", until the middle of the 16th century, as the OED's first definition of the word "Dutch" in English makes clear:

"Of or pertaining to the people of Germany; German; Teutonic."

Of "German" the OED says:

In English use the word does not occur until the 16th c., the n. appearing in our quots. earlier than the adj. The older designations were ALMAIN and DUTCH (DUTCHMAN); the latter, however, was wider in meaning.

Quite why the change occured, and "German" came in, I don't know: perhaps we needed to distinguish more clearly the "Netherlanders" or "Low Dutch" from the "High Dutch".

Panjomin said,

January 14, 2010 @ 9:59 pm

OK, someone had to be the one to ask, so here goes. Why is it Marseille in French and Marseilles in English? That's what a quick Web check tells me, but no explanation for the difference. Apologies if y'all solved this one ages ago.

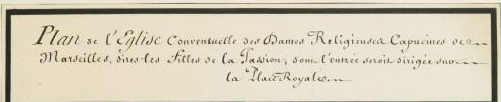

[(myl) In English, it's sometimes one and sometimes the other. In the past 30 days, the NYT has printed 3 "Marseille" and 4 "Marseilles", for example. Though I don't know the history, perhaps in the past, French usage was also varied — thus this caption from 1788

("Plan de l'église conventuelle des Dames Religieuses Capucines de Marseilles [sic], dites les Filles de la Passion … ")

is one of 416 results for a search for "Marseilles" at gallica.bnf.fr. Some of the hits are English works, but many (most?) are not. Of course, there are more than 26,000 hits for "Marseille"… ]

Paul said,

January 14, 2010 @ 10:12 pm

Wandering a little further down this garden path: Does anyone know how Greece/Hellas came to be Yunanistan in Turkish? It's been bugging me for years now.

James Kabala said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:13 pm

Paul: Maybe it is derived from Ionia? The ancient Hebrew name was Javan (or at least it is in English Bibles; presumably in Hebrew itself it is something like Yavan). This is also derived from Ionia, I believe, and it seems possible that the Hebrew could have influenced the Arabic and the Arabic in turn could have influenced the Turkish.

James Kabala said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:16 pm

Oddly, the name Ionia itself in modern English refers to a part of modern-day Turkey, but I believe in Classical times the name was also used to describe the Aegean islands and even parts of the mainland such as Attica (the Athens area).

James Kabala said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:18 pm

Ionia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ionia

Javan: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Javan (The article notes, "The Greek race has been known by cognate names throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond—even in Sanskrit (yavana).")

Charles said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:25 pm

@Russell (5:06): It is true that some South Korean renderings have tended to follow (American) English renderings, but this is not always true, and I think it is changing even more now. All the news reports are pronouncing Haiti in a close approximation of the French fashion, and are printing it as 아이티 (a-i-ti).

As for other place names, Tokyo is a good example of a difference between AE and SK pronunciation. As far as I know, it used to be pronounced as three syllables in AE (I don't know if it still is), but it has always been pronounced as two syllables in Korean.

In a lot of cases, SK renderings have been based more on the way the word is *spelled* in English rather than the way it is *pronounced*, and I think "Tokyo" is an example of that. Until recently, the last syllable of the name of the English football club Tottenham was pronounaced with the "h" sound, but then it was changed to sound more like "um." (The same went for the pronunciation of Binghamton, where I went to school–I don't know if they've changed that one yet.)

It's all very confusing, to be honest, and not quite as clear cut as you might think. I can say that the trend these days seems to be moving toward native pronunciations, although place names that have long been in circulation (like 미국 (mi-guk) for the U.S.) will probably not change.

Drew Ward said,

January 14, 2010 @ 11:43 pm

Along similar lines I've often wondered why so much of the US seems set on referring to Louisiana as Looziana or Loozianer when this pronunciation is almost entirely limited to Texas transplants within the state. Even Popeye's, a New Orleans based fast-food restaurant has chosen "Looziana…Fast" as its motto for its current national advertising campaign.

John Cowan said,

January 15, 2010 @ 12:04 am

Mr. Punch: What's so odd about calling a region by its Latin name in English and by its French name in French, meaning "New Scotland" in either case?

Nathan Myers, myl: I can't find specific authority for this, but it seems clear that there is a connection between the form Legorno and the province of Liguria. Livorno is just south and east of the province, and the region of the Mediterranean that washes both is the Ligurian Sea. This could either be a genuine regional variant or a matter of folk etymology, I can't tell which.

In particular, the American chicken breed called leghorns — for which Foghorn Leghorn is named — were formerly known in America as Italians, and are said to have been imported from various ports of the Ligurian Sea, not necessarily Livorno itself. According to Wikipedia, the traditional pronunciation of Leghorn is reduced: /ˈlɛɡərn/, but not so for the chickens.

Jonathan Gress said,

January 15, 2010 @ 12:06 am

From Wikipedia:

The name Mumbai is an eponym, etymologically derived from Mumba or Maha-Amba—the name of the Koli goddess Mumbadevi—and Aai, "mother" in Marathi. The former name Bombay had its origins in the 16th century when the Portuguese arrived in the area and called it by various names, which finally took the written form Bombaim, still common in current Portuguese use. After the British gained possession of the city in the 17th century, it was believed to be anglicised to Bombay from the Portuguese Bombaim. The city was known as Mumbai or Mambai to Marathi and Gujarati-speakers, and as Bambai in Hindi, Persian, and Urdu. It is sometimes still referred to by its older names, such as Kakamuchee and Galajunkja. The name was officially changed to its Marathi pronunciation of Mumbai in November 1995. This came at the insistence of the Hindu nationalist Shiv Sena party, that had just won the Maharashtra state elections and mirrored similar name changes across the country. However, the city is still commonly referred to as Bombay by many of its residents.

A widespread explanation of the origin of the traditional English name Bombay holds that it was derived from a Portuguese name meaning "good bay". This is based on the fact that bom (masc.) is Portuguese for "good" whereas the English word "bay" is similar to the Portuguese baía (fem., bahia in old spelling). The normal Portuguese rendering of "good bay" would have been boa bahia rather than the grammatically incorrect bom bahia. However, it is possible to find the form baim (masc.) for "little bay" in 16th-century Portuguese. Portuguese scholar José Pedro Machado in his Dicionário Onomástico Etimológico da Língua Portuguesa (Portuguese Dictionary of Onomastics and Etymology), seems to reject the "Bom Bahia" hypothesis, asserting that Portuguese records mentioning the presence of a bay at the place led the English to assume that the noun (bahia, "bay") was an integral part of the Portuguese toponym, hence the English version Bombay, adapted from Portuguese.

Mirat-i-Ahmedi referred to the city as Manbai in 1507. The earliest Portuguese writer to refer to the city as Bombaim was Gaspar Correia in 1508, as recorded in his Lendas da Índia ("Legends of India"). Portuguese explorer Duarte Barbosa mentions a reference to the city in a complex form, as Tana-Maiambu or Benamajambu in 1516.Tana appears to refer to the name of the adjoining town of Thane, and Maiambu seems to refer to Mumba-Devi, the Hindu goddess after which the place is named in Marathi. Other variations of the name recorded in the 16th and the 17th centuries are, Mombayn (1525), Bombay (1538), Bombain (1552), Bombaym (1552), Monbaym (1554), Mombaim (1563), Mombaym (1644), Bambaye (1666), Bombaiim (1666), Bombeye (1676), and Boon Bay (1690).

Jonathan Gress said,

January 15, 2010 @ 12:19 am

Regarding Haiti, I guess what's curious is that [heiti] is only partly a spelling pronunciation. Sure, the digraph in English is usually pronounced [ei], but a final pre-pausal is more likely to be pronounced [ai], the so-called 'long i', than as 'short' [i] (think of all those 'learned' Latinizing plurals in [ai], like 'alumni'). However, as final 'short' [i] is so common in the English lexicon and in English morphology (though usually written ), it is not surprising that English speakers would pick [i] over [ai], perhaps unconsciously interpreting the second syllable as a derivational morpheme.

Regarding the first vowel, [ai] and [ei] seem to be equally plausible, at least if English speakers are interpreting it as the vowel of the root morpheme. The choice of [ei] has to rest with the spelling; French [a.i.ti] is obviously vastly more likely to be heard by English speakers as [aiti] then [eiti], and the initial [h] of the English pronunciation is the dead ringer, since it doesn't even exist in the French pronunciation, but only in the spelling.

Jonathan Gress said,

January 15, 2010 @ 12:20 am

Oops i confused by idioms. I meant dead giveaway, not dead ringer.

Panjomin said,

January 15, 2010 @ 1:08 am

Thanks for the info on Marseille(s)!

Might it be that the French original was plural (based on a mis-parsing of the Greek Massilia as plural?) and went over to English that way? Then the French retro-corrected to a singular without telling their neighbors. (I'm making this up and await correction.)

Re Yunanistan: The Turkish doubtless originates from (or from the same source as) the Arabic al-Yunan, which originates from (or from the same source as) Hebrew Yavan. All of these go back to "Ionia," though why folks in the East picked that region to name the whole country after, I don't know.

Joe Smith said,

January 15, 2010 @ 2:16 am

Can I nail this pronunciation of Cote d'Ivoire down once and for all!!

This is the official name of that country, and the government explicitly title's the country Cote d'Ivoire, that's why it's not correct to use Ivory Coast.

Otherwise it would be like calling Pierre, Peter if you're speaking English

[(myl) It's true that Côte d'Ivoire is the official name. But it's similarly true that thousands of others countries, regions and cities have official names that are quite different from the standard English names — and similarly true, in the other direction, that the press in non-English-speaking countries uses translated or transliterated versions of English-language place names that are quite different from the English versions.

The only difference is that (for example) Finland, whose name in Finnish is Suomen Tasavalta, is happy enough to be called in English the Republic of Finland, whereas the Ivorian government actively discourages the use of English, Russian and other non-French versions, and wants to insist on being called things like the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire (with the accent circonflex, s'il vous plaît). Some comply (e.g. the Economist, National Geographic) and some don't (BBC, NYT).]

Craig Russell said,

January 15, 2010 @ 2:55 am

@James Kabala

Geographically, the Greeks used "Ionia" to describe the same part of the Western coast of Turkey you mention.

Ethnically and linguistically, the Greeks singled out a group of people and the dialect they spoke as "Ionian". This group included the Athenians and the Athenian (Attic) dialect of Greek, which is part of the Ionic group of ancient Greek dialects. Many of those people colonized Ionia (western Turkey), which is where the name came from.

This migration had already happened by the beginning of the period for which we have written history. The 5th century BC Greek historian Herodotus discusses their migration and the Ionians in general in many places, e.g. 1.142 ff:

http://old.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126&layout=&loc=1.142

Craig Russell said,

January 15, 2010 @ 3:12 am

And, to get back somewhat to the topic, it's fascinating to look at how ancient Greek proper names are Anglicized. Up until around a hundred years ago, it was almost universal practice to Latinize the name, and then Anglicize the Latinized name. This leads to the familiar Achilles, Ajax, Socrates, Oedipus, Alexander. (Also, up until the nineteenth century, Greek gods in Greek contexts were generally called by their Roman counterparts–Zeus was Jupiter, Aphrodite was Venus, etc.)

But there has been a big move in Classical scholarship toward using transliterated versions of the original Greek spellings of these names–leading, for example, to Akhilleus for Achilles, Aias for Ajax, Sokrates for Socrates, Oidipous for Oedipus, Alexandros for Alexander.

I'm not a big fan of this trend–I find it visually unpleasant as well as potentially confusing for students new to the material who might find the same character's name spelled several different ways in several different texts. And it's oddly inconsistent–there are several names that, for whatever reason, are always left in the old form (e.g. you never see Athenai for Athens, Helene for Helen, Platon for Plato, Aristoteles for Aristotle, and Corinth sometimes becomes Korinth, but not what it should, by this rule, become: Korinthos).

Mark Anderson said,

January 15, 2010 @ 3:38 am

Louis has different pronunciations. BrE speakers tend to say Loo-ee.

In England the National Motor Museum is located at Beaulieu, pronounced Bi-oo-li

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaulieu,_Hampshire

Trix said,

January 15, 2010 @ 4:06 am

@Simon Cauchi – don't know where you're from in NZ, but my family and all the Aucklanders I knew pronounced the car make as REN-oh.

The one I'm still not sure of is Subaru. "Soo-ba-roo" in the modern (US?)parlance, or "Soo-BAH-roo", which is what I was brought up with.

As for the country under discussion, it's /haɪ ˈiː ti/ for people I know in both NZ and Australia.

Peter Taylor said,

January 15, 2010 @ 4:50 am

Charles wrote that in South Korea:

I presume that's with three syllables? As long as I can remember I've pronounced it with two: /'tɑːt nʌm/.

Richard M Buck said,

January 15, 2010 @ 4:54 am

Native UK speaker: I've only ever heard one English speaker pronounce the 's' on Marseilles (ma:'seilz, if you'll forgive the lack of proper IPA – and yes, he is a non-rhotic speaker); he did it, I think, as a deliberate archaism, although he claimed it was merely for consistency's sake, since he pronounced the 's' in 'Paris'. Of course, he also pronounced Lyons just like the animals or the coffee house…

And I still think Haiti has 3 syllables, /haɪ ˈiː ti/ — pace Gordon Brown.

John Walden said,

January 15, 2010 @ 5:01 am

"Ivory Coast" is a special case because "ivory" and "coast" are both English words, just like "united" and "states" are. Would we insist that the Spanish for the US be "Los United States" and not "Los Estados Unidos"? It's what the words mean.

As far as "abroad" is concerned, there is clearly no consistency. It does seem to me that the longer English has been mapping a country or a city, especially by sea?, the more likely we are to have an English name for it. And when the English name predates standardised spelling both in the original language and English, it's pretty much how the dice fell at the time, or later when standard spelling arrived: some British sailor may have shouted to a fisherman "What's the name of this place?" and written down on a map very roughly what he thought he heard, "Majorca" or "Machorcka or whatever, at a time when Spanish was spelling it eight different ways anyway (That's just an example, I don't know what really happened). Since then we've been asked to call it Mallorca and we pronounce it no more accurately as a result.

In general, I don't like being told what to do with my own language by anyone, or telling anybody else what to do with theirs. Why does everything have to be tied down and squared away anyway? English is a great big heaving anarchic lovely mess, it can't be reduced to "Don't wear white shoes before Labor Day"-like dictates. So it's Peking for me but you can say Beijing if you like. It's a free country (!).

And it's not as if it's a particularly English trait. Dover in French is Douvres and The Hague, which isn't even its official name, is whatever it is in lots of different languages: The Hague, La Haye, La Haya and so on.

I won't say Cote d'Ivoire and its inhabitants won't stop saying Grande-Bretagne when they speak French, just on somebody's say-so. And especially not then, in my case.

stormboy said,

January 15, 2010 @ 6:05 am

@James: "

Like Jackie, I distinctly remember always hearing 'Haiti' pronounced with three syllables here in Britain – and I'm in my twenties, so it can't be a longstanding shift. In fact, I was taken aback for a moment when I heard the 'anglicized version' on the BBC this morning. I'd only ever heard Americans say it that way before."

I'm from London (UK), in my 30s and was also sure that Haiti used to be pronounced here as James describes. I was beginning to wonder if I'd imagined it!

Regarding 'Port-au-Prince', there seems to be varying usage on the BBC. A few days ago I was hearing 'Port' as in English, 'au' like English 'oh' and 'Prince' close to the French but without the uvular 'r'. Listening to the BBC World Service this morning, it seems that newsreaders are pronouncing 'Prince' as in English. And this very second I've just heard a newsreader refer to 'Ivory Coast'.

Waffles said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:03 am

Another thing that can happen is that the understanding of how to pronounce certain things can change; the "x" in "Mexico" originally represented a "sh" sound; Meshico. I don't know if anybody pronounces it that way anymore, though. I guess both Americans and Spanish speakers pronounce it like we would any other kind of X in our given language.

Ben Hemmens said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:04 am

Yes, but many of the versions of foreign placenames (not just in English) were fixed in the days when practically nobody got to hear someone from the foreign country speaking. I think there's something to be said for gently approximating how we pronounce (and spell) them a bit closer to the originals.

Especially here in Europe, now that we have a Union, and spend most of our time doing business transnationally, we could do each other that courtesy. The same goes for orthography and foreign diacritics, especially in people's names; handling these properly is mostly a matter of software.

Ben Hemmens said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:09 am

@ John Cowan:

I guess Leghorn is a classic eggcorn.

Ben Hemmens said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:22 am

@LanguageHat:

"I find this idea that English-speakers should approximate the pronunciations of other languages tiresome and invidious. Geographical names are words like any other; they are part of the language and conform to its rules and habits,"

ahh… which, as we know, are not immutable. Just to be clear: I'm not proposing this should be enforced by law. I'm just saying that in an age when more people have been there, seen and heard it on the tv, etc. than ever before, it seems natural to shift a bit towards how the respective natives spell and pronounce the names.

And also because we native-speakers now have only a small minority stake in the language. It's the price we pay for it being understood just about everywhere we go.

David Eddyshaw said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:30 am

@stormboy, James

I (aged Brit) have always said Ha-ee-tee, and have always thought "Haytee" was an Americanism (on the lines of "Eye-rack").

It seems (as so often) that the facts may be more complicated.

One thing that occurs to me is that Americans almost certainly have cause to *refer* to Haiti a lot more often than Brits, which in itself would make it more likely that the name would end up domesticated, as it were.

Steve said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:39 am

On older (British) English pronunciations, some literary evidence:

There was an Old Man of Marseilles,

Whose daughters wore bottle-green veils;

They caught several fish,

Which they put in a dish,

And sent to their Pa at Marseilles.

(Edward Lear)

—-

"Shortly after this the cruel Queen [Mary] died and a post-mortem examination revealed the word 'CALLOUS' engraved on her heart."

(Sellar & Yeatman, 1066 And All That, Chapter 32, page 65 — After losing Calais to the French, Mary is reported to have said "When I am dead," she said, "you will find 'Calais' graven on my heart.")

mollymooly said,

January 15, 2010 @ 8:02 am

The change from "Persia" to "Iran" was done by the Shāh; though he wasn't as awful as the Myanmar junta, he was hardly a model of propriety.

Peter Taylor said,

January 15, 2010 @ 8:31 am

Waffles wrote

According to the Real Academia Española, a Spanish x which is followed by a vowel is usually pronounced /ks/ or /gs/ but is /j/ in México, Oaxaca, …

I understand that the phonetic spelling Méjico is considered derogatory by many Mexicans.

stormboy said,

January 15, 2010 @ 8:51 am

@Waffles: "the "x" in "Mexico" originally represented a "sh" sound; Meshico. I don't know if anybody pronounces it that way anymore, though."

Portuguese speakers do.

Ellen K. said,

January 15, 2010 @ 8:55 am

Basically, in Mexican words derived from Mexican Indian terms, X is pronounced like a J usually is in Spanish, which can vary from like an English H to something like the end sound in loch. Not like the IPA /j/.

dwmacg said,

January 15, 2010 @ 9:52 am

The letter X usually represents the sound we write in English as "sh" in Iberian languages (Portuguese, Basque, Catalan, etc.; that's why you get all those "tx"s in Basque that represent the affricate that in English and Spanish is spelled "ch") and that used to be true for Castillian, before the fricative migrated toward the back of the vocal tract. So Mexico was originally pronounced something like "Meshico". (And I remember reading once that the city we know as "Oaxaca" was spelled "Washaca" or perhaps "Wachaca" in French, but now I can't find a source for that.)

When I'm speaking Spanish I do my best to use the Spainish version of place names, but I find it impossible to make myself say "Nueva York".

Peter Taylor said,

January 15, 2010 @ 9:59 am

Sorry, I translated from the DRAE without checking whether it was using IPA.

John said,

January 15, 2010 @ 10:43 am

Latin was routinely pronounced in European languages as if it were the native language. Now the restored pronunciation is creeping in.

Classicists (I am one) nearly always apologize in their forwards for inconsistent Greek-name spellings in their books.

MI-lan is the soccer team in Italy, even though the city is Mi-LA-no. I don't know why, but that's the way they do it. (Lots of Italian city-names are very old in English and reflect many of the various things talked about in this post & comments.)

A side note, the Byzantines called themselves "Romaioi" as heirs to the Roman empire, and there was some debate upon the founding of modern Greece whether to continue with this name. They didn't and went old-school with Hellenes. Nevertheless we continue to call them what the Romans did – mistakenly because the Graeci were but one tribe/ethnicity within the larger Hellenic grouping.

dwmacg said,

January 15, 2010 @ 10:58 am

Like a lot of football teams, A.C. Milan was founded by English expats, so that probably explains the use of the English form of the name. My own favorite team is Athletic de Bilbao; during the Franco years they and their daughter team in Madrid were forced to change to Atlético, but after his death in a strange reflex of linguistic nationalism the team in Bilbao switched back to the English form while the Madrid team kept the Spanish form.

language hat said,

January 15, 2010 @ 11:05 am

the Ivorian government actively discourages the use of English, Russian and other non-French versions, and wants to insist on being called things like the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire

And it is pathetic that so many people leap to do the bidding of foreign governments that don't even have the power to punish them for noncompliance (as their own government does).

[(myl) Well, in some cases people just use foreign names, independent of any official intervention. But it's certainly ironic that the government in question continues to use the standard French calques for the names of other countries, e.g. "États-Unis" for "United States".]

MI-lan is the soccer team in Italy, even though the city is Mi-LA-no. I don't know why, but that's the way they do it.

It's ultimately because soccer/football was an English import, and everything to do with it was imbued with Englishness. The official name of the club, when it was founded in 1899 by six Englishmen, was the Milan Cricket and Football Club. The rest of the name has been Italianized to Associazione Calcio Milan, but the foreign "Milan" remains; I presume the initial stress is a signal of foreignness, but I'd be curious to hear from someone who knows more.

Słowosław said,

January 15, 2010 @ 11:24 am

Ivory Coast/Côte d'Ivoire reminds me of how "Crna Gora" ("black mountain" in Serbian) becomes "Montenegro" ("black mountain in Italian) for the English name of the country. Are there other calques like this in English names of countries (or other places)?

dwmacg said,

January 15, 2010 @ 11:49 am

I'd agree to refer to the Ivory Coast as "Côte d'Ivoire" iff the government of that country will agree to always refer to every other country in the official form that is used in that country, using whatever the local script is in written documents (with all appropriate diacritics, of course). (In cases where there are different official names in different languages, as in Switzerland, I'd expect them to use all the different forms.)

Coby Lubliner said,

January 15, 2010 @ 11:54 am

@myl: The only difference is that (for example) Finland, whose name in Finnish is Suomen Tasavalta, is happy enough to be called in English the Republic of Finland. Yes, but Republiken Finland (in Swedish) is also official, which is why the country identifier on Finnish cars is SF.

@mollymooly: Both the shah of Persia and the junta of Burma claimed to have changed their countries' names in the name of ethnic diversity, in that there are Iranians who are not Persians (Kurds, Azeris etc.) and there are Myanmarese who are not Burmese (Shan, Karen etc.).

@Słowosław: Italian for "black mountain" is monte nero. The form with the G is probably Venetian.

Jesse Tseng said,

January 15, 2010 @ 12:33 pm

Coming soon: "In a world where threaded comments are an unsupported functionality, veteran Mark Liberman struggles in the aftermath of another overly successful linguistic's blog post, as he eats a second breakfast…"

[(myl) I wish our antique WordPress installation supported threaded comments! There was (is?) a plugin for that, which I once tried and failed to get to work. Trying again is on my list of Things To Do, down below upgrading the basic WordPress version to something vaguely current.]

About Marseilles (see Panjomin, January 14 @ 9:59 pm):

The -s found in many French city names can have several origins, the most common of which are root consonant (Paris, Naples, …) and oblique plural ending (usually referring to the members of some tribe: Chartres, Angers, Tours, …) There are probably also cases where it's a nominative singular ending (as in the personal name Charles). But Marseilles doesn't fall into any of these categories (nor, as far as I know, do Londres, Gênes, Lyons, …) But I think that the number of names with an etymological -s was so large that this ending came to be reinterpreted as a typical suffix for city names, and then extended to other members of the class. In the same way, the etymological -s of plus, moins, dans, etc., spread by analogy to words like alors, sans, and doncques — just to make them look more like adverbs. In both cases ("city-name s" and adverbial s), sometimes the new ending stuck, and sometimes it didn't.

English mismatches like Marseilles and Lyons could then be explained as borrowings from French from the relevant period. The OED suggests that this happened as late as the 18th century, but it seems to me that the names of these cities must have been familiar to English speakers long before that.

CIngram said,

January 15, 2010 @ 1:07 pm

My resistance to adopting new names, spellings or pronunciations for places- not only foreign places- is in direct proportion to the amount of apparent political manipularion involved. Manifest absurdity also comes into it, as is the case with (the) Ivory Coast.

@Peter Taylor

I understand that the phonetic spelling Méjico is considered derogatory by many Mexicans.

Derogatory is perhaps a bit strong, but there is a strong sense in Mexico that the 'x' is part of their identity. Where I live there is a 20ft statue presented to us by the Mexican Academy, known as the Aztec Quijote, and supposedly representing that rather confused gentleman, but in fact it is simply the letter 'X'.

For some reason the adjective 'mejicano' is always spelt with a 'j'.

@dwmacg

¡Aupa Athletic!

By the way, before the war, didn't we speak of 'the Argentine'?

Simon Cauchi said,

January 15, 2010 @ 1:44 pm

@Trix – No doubt the New Zealanders I've heard pronouncing "Renault" in an anglicized way had never learned French. Your friends in Auckland presumably have.

Kate G said,

January 15, 2010 @ 1:50 pm

Canadian Governor General Michaelle Jean is originally from Haiti and has lived in Canada for 40 years or so. In this moving video http://www.thestar.com/videozone/750401 she says "Haitian" at the beginning (it seemed to be between one and two syllables for the HAI part), and "Haiti" at about the two minute mark which seemed to clerly use only one syllable for the HAI part. She also speaks some Creole and I would be interested to know if she says Haiti the same in the Creole section as in her English translation of it.

Stephen Jones said,

January 15, 2010 @ 3:44 pm

Except of course the language of Mallorca wasn't Spanish but Catalan.

Carlos said,

January 15, 2010 @ 3:44 pm

I would assume the pronunciation has just been americanized.

Today (formerly todaie) is still pronouced with an ai in Austrailia.

Tokay still in Britain prononce it to-kai; I've heard it locally as to kei,

Hayti probably has the same roots as being pronounced with an hai originally, and currently in places that haven't monophthongised the /ai/ into more of an /e:/.

Aviatrix said,

January 15, 2010 @ 7:28 pm

I say "hatey" for the country but "ha-ee-shun" for a person. And I would giggle if I heard Port-au-Prince pronounced as the English "prince." Its being embedded in a French phrase kind of precludes that. (Mind you, I'm the one who got laughed at for her intention to clear customs at Meen-O, ND. I never would have guessed Minot was pronounced My-not).

Bob Ladd said,

January 16, 2010 @ 4:14 am

A lot of the issues about what we "should" call foreign places were discussed a couple of years ago, shortly after LL began accepting comments. That discussion is relevant to this thread as well.

Jane Shevtsov said,

January 16, 2010 @ 9:44 pm

Germany is the most puzzling to me. In Russian, Germany is Germania (with a hard G), but German (for the language or as an adjective) is Nemetzkiy. Does anyone know how this came about?

V Antonelli said,

January 16, 2010 @ 11:31 pm

English took "Marseilles" from French when it was spelled that way. English kept the spelling, French changed it.

[(myl) Do you have any evidence for this view? I checked in the Gallica archive, with the results reported briefly here, which was that in pre-1789 french texts, the version with final 's' does occur occasionally, but still as a small minority of cases.

For example, in works published before 1700, Gallica has 1 instance of Marseilles (from 1688), and 98 instances of Marseille (from 1572 onwards).

So when was it that "'Marsellies' … was spelled that way" in French? And how do you know?]

V Antonelli said,

January 16, 2010 @ 11:45 pm

not very germane, but: Greeks have lived on the shores of the Black Sea since something like 1000 BCE. some are still there (in Turkey, Ukaine …), though many (~300,000) were exterminated, along with even more Armenians and Assyrians, during the "population exchange" following WW1.

V Antonelli said,

January 16, 2010 @ 11:49 pm

re Marseille(s): i don't have any kind of original sources at my disposal. this is what several french teachers have told me over the years. maybe they're wrong. a couple of them were actually *from* France, so i assumed they knew what they were talking about.

V Antonelli said,

January 17, 2010 @ 12:38 am

more Marseille(s): here's someone who seems to know something about it, though he doesn't name sources either:

http://www.linguism.co.uk/index.php?s=lyon

(half way down the page)

Panjomin said,

January 17, 2010 @ 1:20 am

@ V Antonelli 12:38

Thanks for the very informative place-names link!

Hans said,

January 17, 2010 @ 5:27 am

@ Coby Lubliner: Yes, but Republiken Finland (in Swedish) is also official, which is why the country identifier on Finnish cars is SF. The country identifier was changed in 1993 to FIN.

Mark Heyne said,

January 17, 2010 @ 8:18 am

I lived in Qatar for a few years and was irritated at news-readers and foreigners in general calling it 'catarrh' rather than 'cutter' which approximates better to the Arab pronunciation. It helps, mind you, to have a bit of catarrh to get it sounding right!

mollymooly said,

January 17, 2010 @ 9:08 pm

@Mark Heyne

"Qatar" is nowadays pronounced more Arabic-like in the UK, since Qatar Airways is a prominent sponsor of TV and sport.

dw said,

January 17, 2010 @ 10:43 pm

@Sven:

Actually "van Gogh" is usually pronounced in Britain as /væn ˈɡɒx/ or /væŋˈɡɒx/, which isn't that remote from the Dutch pronunciation (according to Wikipedia, is [faŋˈxɔx])

I was quite surprised when I came to the US and heard it pronounced /væn ˈɡoʊ/ !

Sven said,

January 18, 2010 @ 1:06 am

@ Jane Shevtsov: In Russian, Germany is Germania (with a hard G), but German (for the language or as an adjective) is Nemetzkiy. Does anyone know how this came about?

In Russian, "mute" is немой and "German" is немец; in Polish, niemy and Niemiec (and the country Niemcy); in Czech, němý and Němec (and Německo); in Croatian, nijem and Nijemac (and Njemačka); in Serbian, nem and Nemac (Nemačka); and so on.

AFAIK, the probable origin is that the Slavs viewed their Germanic neighbors, whose language was not mutually intelligible with old Slavic, as "mutes". However, I cannot guarantee that this is not just a case of folk etymology.

Kragen Javier Sitaker said,

January 18, 2010 @ 10:57 pm

[ɦ], really? What dialect of English is that from?

Kenny Easwaran said,

January 18, 2010 @ 10:58 pm

And Hungarian has "német" for "German". I assume this is borrowed from Slavic, like "Csütörtök" for "Thursday", but it seems odd to have borrowed a Slavic name for the language of the ruling emperor of most of the last few centuries.

dwmacg said,

January 19, 2010 @ 5:04 pm

Wikipedia mentions the tribal name Nemetes as another possible source for the Slavic term. That sounds more plausible, and is parallel to other source names for the Germans, although the Nemetes were located fairly far west to serve as a source for the Slavs.

Alex said,

January 19, 2010 @ 11:49 pm

"I wish our antique WordPress installation supported threaded comments!"

Do you need help upgrading?

Andii said,

January 24, 2010 @ 4:09 am

Liike David Eddyshaw, I was brought up saying 'Ha ee tee'. I think that I picked that up from the BBC and it would have been the 70s. I was beginning to wonder whether I'd pciked up some idiosyncracy. However, for most of my life 'Haytee' has been the 'American' pronunciation.

Andrew F said,

January 26, 2010 @ 12:14 pm

Somewhat late I know, but a member of the BBC Pronunciation Unit has provided an article explaining its choice.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/magazinemonitor/2010/01/how_to_say_haiti_and_portaupri.shtml

Jongseong Park said,

January 27, 2010 @ 10:30 am

In response to Russell's comment, there are indeed significant differences in the names used for countries and major cities in North and South Korea, at least officially. Some are systematic transcription differences. In South Korea, unvoiced plosives /k/, /p/, and /t/ in languages that only have voiced-unvoiced distinctions are uniformly mapped to the aspirated series in Korean, while North Koreans make the effort to map the unaspirated plosives in languages like Spanish and Russian to the 'tense' series in Korean. So Paris is 'Phari' in the South and 'Ppari' in the North (apologies for the ad hoc romanizations I will be using throughout). The sound /v/ is always mapped to the plosive /b/ in South Korea, but North Koreans sometimes map this to /w/. For example, Warsaw is approximately 'Barshaba' in the South but 'Warshawa' in the North. It is hard to tell whether this is a systematic rule or if it's just based on some Russian pronunciations where the phoneme /v/ is pronounced [w].

The difference you alluded to, however, goes beyond transcription differences and comes down to the question of traditional names versus locally used names. 'Traditional', of course, is relative here; the traditional Korean names for China and Japan, 'Jungguk' and 'Ilbon', continue to be used in both Koreas. But for place names introduced in modern times, North Korea has been more willing to officially mandate names based on the locally used ones instead of the more established forms based on auxiliary languages (English, Japanese, Russian).

South Korea has a fairly sophisticated system of transcribing proper names in dozens of foreign languages, and there too the principle is to base Korean transcriptions on locally used names. But exceptions are made for established forms, and country names fall under this category. Sweden and Romania are called 'Sweden' and 'Rumania' preserving the traditional English-based forms, although the rules on transcription of these languages would yield 'Sberiye' (Sverige) and 'Romŭnia' (România). Country names have been introduced mainly through English in the South. A similar thing happened historically with Russian in the North; it's just that the Northerners then decided to overhaul these established forms in favour of locally used forms.

Note, however, that this is just a comparison of officially prescribed usage. In South Korea, you still commonly hear officially deprecated forms of country names, and I imagine it may be similar in North Korea. If you only study place names as they appear on North Korean gazetteers, you may come away with an impression that North Koreans are much stricter about using local forms for foreign place names, when these prescribed forms (which were introduced fairly recently, as I recall) may not yet be in general everyday usage.

In response to Charles, as far as I know, Haiti has always been rendered 'Aiti' in Korean. French names have been pronounced in the French way for a long, long time in Korea. 'Tokyo' is rendered 'Dokyo' in Korean (the initial /d/ in Korean is unvoiced), and it is directly based on Japanese pronunciation. If it were based on the English spelling, it would have been rendered 'Tokyo' with a strongly aspirated /t/. As for Tottenham, it is merely that ad hoc transcriptions by those unaware of English transcription rules nor the actual English pronunciation included the /h/; the official spellings of similar '-ham' names of the UK such as Buckingham have never included the /h/. They never changed the official transcription of Tottenham; it's only that they began to enforce it belatedly.

The problem is that most Koreans never learn the rules and then make up ad hoc transcriptions when they encounter the names through English sources, leading to a proliferation of nonstandard and incorrect transcriptions. And then they complain about the confusion.

John V said,

January 28, 2010 @ 10:52 am

Cole Porter wrote a song called "Katie Went to Haiti" in 1939.

Jongseong Park said,

January 29, 2010 @ 6:00 am

To add to my previous comment, in South Korea the prescripted name for the Moldovan capital is Khishinŏu (after the Moldovan/Romanian Chişinău) while in North Korea I believe it is Kkishünyop (after the Russian Кишинёв Kishinyov). So here is an example where the South Korean form follows the local form more closely while the North Korean form just uses the Russian form (although I do understand Moldova has a significant Russian-speaking minority). In fact, if we examine North Korean names for regions under past Russian/Soviet influence, I think we'll see them generally preferring Russian names over current local ones.