Framing a poll

« previous post | next post »

Back in 2005, when George Lakoff's ideas about "framing" in political discourse were a hot media topic, the common journalistic mistake was to see the issue in terms of words rather than concepts. Now the whole issue seems to have fallen out of fashion — at least, an interesting study, published about a month ago in Psychological Science and featured in the Random Samples section of Science Magazine, hasn't (as far as i can tell) generated a single MSM news story or even blog post.

The paper is Mark Landau, Daniel Sullivan, and Jeff Greenberg, "Evidence That Self-Relevant Motives and Metaphoric Framing Interact to Influence Political and Social Attitudes", Psychological Science 20(7): 1421-1427, November 2009. The abstract:

We propose that metaphor is a mechanism by which motivational states in one conceptual domain can influence attitudes in a superficially unrelated domain. Two studies tested whether activating motives related to the self-concept influences attitudes toward social topics when the topics' metaphoric association to the motives is made salient through linguistic framing. In Study 1, heightened motivation to protect one's own body from contamination led to harsher attitudes toward immigrants entering the United States when the country was framed in body-metaphoric, rather than literal, terms. In Study 2, a self-esteem threat led to more positive attitudes toward binge drinking of alcohol when drinking was metaphorically framed as physical self-destruction, compared with when it was framed literally or metaphorically as competitive other-destruction.

Their simple and clever technique involved three experimental steps, which I'll describe in detail for their first experiment. 69 Arizona undergraduates participated in what was billed as a study about media preferences. In the first step, subjects read an article about airborne bacteria:

[P]articipants in the contamination-threat condition read an article, ostensibly retrieved from a popular science magazine, describing airborne bacteria as ubiquitous and deleterious to health. Participants in the no-threat condition read a parallel article describing airborne bacteria as ubiquitous but harmless.

In the second step, subjects read one of two articles about U.S. domestic issues other than immigration. One of these articles contained a number of "country = body" metaphorical expressions, while the other one didn't:

In the body-metaphoric-framing condition, the essay contained language subtly relating the United States to a body (e.g., "After the Civil War, the United States experienced an unprecedented growth spurt, and is scurrying to create new laws that will give it a chance to digest the millions of innovations"). In the literal-framing condition, the same domestic issues and opinions were discussed using literal paraphrases of the metaphors ("After the Civil War, the United States experienced an unprecedented period of innovation, and efforts are now underway to create new laws to control the millions of innovations").

In the third step,

[P]articipants completed two questionnaires, counterbalanced in order, assessing their agreement with six statements each about immigration and the minimum wage. The immigration items included "It's important to increase restrictions on who can enter into the United States" and "An open immigration policy would have a negative impact on the nation." The minimum-wage measure included statements like "It's important to increase the minimum wage in the United States." Responses were made on 9-point scales (1 =strongly disagree, 9 =strongly agree) and were averaged to form composite scores for anti-immigration attitudes (α= .87) and agreement with increasing the minimum wage (α= .88). Preliminary analyses revealed no significant effects involving presentation order, so we omitted this factor from subsequent analyses.

As a final check, they asked participants "To what extent did the article on airborne bacteria make you more concerned about what substances your body is exposed to?" and "To what extent did the article on airborne bacteria increase your desire to protect your body from harmful substances?". As expected, the subjects in the contamination-threat group were slightly more concerned about exposure to harmful substances than subjects in the no-threat group (mean response 5.64 vs. 4.48 on a 9-point scale, SDs 2.18) and 2.20). Similarly for concern about protecting their bodies from harmful substances (M= 5.60, SD= 2.14 vs. M= 4.70, SD= 2.15).

Our primary prediction was that a bodily-contamination threat would lead to more negative immigration attitudes when the United States was framed in body-metaphoric terms than when it was framed in literal terms, whereas minimum-wage attitudes would be unaffected by this manipulation.

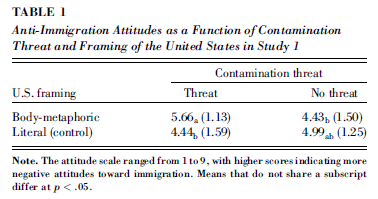

And this is indeed how it came out. Their Table 1 shows the size of the effect on the answers to the immigration question:

The answers to the minimum-wage question were not significantly affected.

I wouldn't have been confident of seeing this doubly-indirect framing effect. Reading an article about the dangers of airborne bacteria influenced answers about immigration — but only if a second article, on a separate topic like innovation, used body-metaphoric language in referring to the United States.

The most surprising thing is that reading about bacterial contamination didn't influence answers to questions immigration attitudes when the intermediate article didn't use "country = body" expressions. The underlying metaphor in that case is so ubiquitous that you'd think it would always be activated to some extent.

The second most surprising thing is the media silence. I guess the cause is some combination of fashion (framing is old news), distraction (the study wasn't about health care, climate change, or Sarah Palin), and complication (this line of research doesn't give political operatives any clear marching orders).

Jerry Friedman said,

December 20, 2009 @ 10:04 am

That's really amazing.

I wonder what would have happened if the researchers had skipped the essay on innovation and given the participants questionnaires on immigration, one that used country-as-body metaphors and another that didn't.

And as I often do when there's an advance in psychology, I expect this to be misused before it's used beneficially (if it ever is). When anti-immigration pundits and bloggers find out about it, I'll bet they'll start playing up stories about bodily contamination and using more country-as-body metaphors—or maybe they already have. Other propagandists will do the same, if they see opportunities.

On a linguistic note, maybe it's just because it's earlier than I usually get up (I'm doing a Christmas Bird Count today), but I had a lot of trouble parsing this sentence:

"Two studies tested whether activating motives related to the self-concept influences attitudes toward social topics when the topics' metaphoric association to the motives is made salient through linguistic framing." I was on motives of the activating type and influences related to the self-concept.

Franz Bebop said,

December 20, 2009 @ 11:24 am

These results don't surprise me. This effect is obvious.

Republicans have been using framing as a political tool for as long as I can remember.

[(myl) With respect, I think you might not be paying attention. The experiment was NOT about how the survey question (e.g. about immigration) was phrased. Nor was it about how an issue (e.g. immigration) was presented. Rather, it was a three-way interaction among (1) whether or not an article about environmental bacteria depicts them as dangerous; (2) whether or not an article about an irrelevant topic uses routine body metaphors in describing national actions and states; (3) how subjects responded to a neutrally-phrased question on immigration.

I haven't seen any evidence that political operatives have been thinking or working at this double level of abstraction: "let's start a hand-washing campaign, and let's use lots of phrases about America sitting or standing or reaching, because if we do those two things, without ever mentioning the question of illegal immigration, the power of metaphorical transfer will make people more worried about that issue…" (I'm not sure this would work, either; but anyhow, the effect described in this paper is anything but obvious.)]

An even more interesting question is the meta-question: Why is it that some observers can perceive the effects of framing while others can't? How come this isn't obvious to everyone?

I don't agree that the topic has fallen out of fashion. Framing as a political and rhetorical tool is being used right now to defeat health care reform in the US. But the media silence does not surprise me. Many people expressly do not agree with Lakoff's views. The media don't comment on Lakoff because they don't realize that he is right.

http://integral-options.blogspot.com/2008/08/who-framed-george-lakoff.html

fev said,

December 20, 2009 @ 1:03 pm

"Many people expressly do not agree with Lakoff's views. The media don't comment on Lakoff because they don't realize that he is right."

Well — kinda-sorta-maybe. Commenting on Lakoff isn't the same as reporting on Lakoff, and broad speculation about what "the media" are up to tends to see conspiracies in a lot of stuff that (imho) is better attributed to news routines and cultural practices. There was quite a bit of reporting on the "death panel" frame (which underscores Mark's suggestion that the best way to get a bit of framing research onto the news agenda would be to allow editors to run pictures of Sarah Palin with it).

Lots of good quantitative research has found framing effects from, say, news values or valence. Why it doesn't show up in general news accounts is anyone's guess. No doubt it's partly because it hasn't shown up on a talk show to support the Men And Women: We're Still Different! idea (though Grabe & Kamhawi's "Hard wired for negative news? Gender differences in processing broadcast news" would be a great test case). Maybe someone's article about Harry Potter and the Survey Class at a Major Midwestern University got the university news bureau's attention that day.

But framing research does risk running headlong into news practice. I'd say most journalists "realize" that Lakoff is right, in that "death panel," "death tax" and the like tend to stack the cognitive deck. (Why do you suppose Fox News changes "suicide bomber" to "homicide bomber" in AP texts?) The trouble is that choices seen as central to news judgment and independent, "objective" decision-making (whether a story is a "conflict" or a "pocketbook" issue, to point to Claes de Vreese's cool framing work) have the same sort of outcomes. The issue isn't realizing that loaded language is loaded; it's acknowledging that "objective" language is loaded too.

[(myl) What's interesting about this research is that it's not about any sort of issue-language ("objective" or "loaded") at all. It's about how irrelevant emotionally-loaded concerns (e.g. contamination by environmental bacteria) can allegedly be transferred by activation of irrelevant ordinary-language metaphors (e.g. nation as embodied individual) into a fairly large (d ~ 0.8-1.1) effect on opinion in a domain not mentioned in either of the first two steps.]

Keith M Ellis said,

December 20, 2009 @ 1:16 pm

Because only a small minority of people are meta-critical. (Maybe that's not the best way of describing it, but that's what comes to mind at the moment.)

I don't think that most people think at all about how they think about things. But the people that do take a habitual meta-critical stance are very aware of these sorts of biases. That doesn't make them immune from it, just much more aware of it.

This may be a trivial observation, but I've long believed that the overwhelming majority of beliefs are not in almost any way the product of organized, rational thought but rather are conformational/intuitive unreflective positions that are ex post facto rationalized in a very weak and opportunistic fashion. Furthermore, and importantly, most people are truly unaware of this and tend to be somewhat idealistic about their beliefs, tending to assume that they are coherent, well-intentioned, and rational while, simultaneously, they tend to assume the opposite about the beliefs of those they deem their opponents. Thus the majority of civic discourse is posturing and ungenerous.

Kevin said,

December 20, 2009 @ 2:47 pm

Has anyone done any research on how persistent the effects of framing are?

uberVU - social comments said,

December 20, 2009 @ 3:00 pm

Social comments and analytics for this post…

This post was mentioned on Twitter by languagelog: Framing a poll: Back in 2005, when George Lakoff's ideas about "framing" in political discourse were a hot media to… http://bit.ly/4s0XJa…

Ankush said,

December 20, 2009 @ 5:35 pm

The parameters of the study look at an immediate response. I agree with the comment by Kevin that the effects of a few questionnaires will be different than being bombarded by the talking points repeated by multiple sources and generating fear not only through metaphor and "framing" but innuendo as well.

CBK said,

December 20, 2009 @ 5:43 pm

Study 1 reminds me of Gick and Holyoak's 1983 study on analogical reasoning. This used metaphors of war and disease—and found little transfer. (The idea was to see if students would use the strategy suggested in one scenario about a general trying to attack a fortress to solve a problem described in a second scenario about using "rays" of unspecified type to destroy a tumor.) Gick and Holyoak's study differs in many ways from Landau et al.'s Study 1, but one difference that Study 1 suggests is viewpoint. (Technically this might be "person deixis" but I am no expert on this.)

In the two parts of Landau et al., it appears that the subject's viewpoint is similar: "your body" and—presumably—"your country." In Gick and Holyoak's study, the subject first reads about a general who wishes to capture a fortress, then reads in the second part "You are a doctor."

fev said,

December 20, 2009 @ 6:04 pm

"Has anyone done any research on how persistent the effects of framing are?"

(Confident that our genial host will step in if I'm wrong) It depends a bit on what you think frames are, where they live, and how they and their effects are or should be measured.

[(myl) Exactly. And in addition to the explicitly political or media-related research that fev cites, there's an enormous psychological literature on "priming", "frequency", and "recency" effects, among other things, some of which might count as "framing".]

On the persistence of a framing effect like the one described above, I don't know of much. De Vreese (2003) found that the effect of strategy (+/- "horse race") framing on political cynicism was significant in an immediate posttest but didn't persist in a second test a week later. Other studies have found some evidence of lasting effects. Long-range testing is problematic not just because of intervening exposure but because of all the other things (issue knowledge, depth of processing, prior attitudes) that can affect whether a frame works its magic in the first place. There's stronger evidence of persistence in related fields like agenda-setting, in which repeated exposures are expected, but that's really a whole different fish.

If you consider frames in media accounts to be outcomes themselves, as the sociology-rooted side of framing does, then frames are assumed to be persistent (Gitlin's "The Whole World is Watching" is an explicit example). Those frames can be created or changed on short notice, as in the "war on terror," and content analysis suggests that the persistence of such a frame isn't solely tied to support for the incumbent administration. And that's not at all the sort of thing you get to manipulate in the lab, unfortunately. (Pls don't tell Gov. Palin we say "manipulate," because that's a whole different framing issue.)

Jonny Rain said,

December 20, 2009 @ 7:01 pm

Methods/results very much remind me of studies in Terror Management Theory.

Franz Bebop said,

December 20, 2009 @ 9:20 pm

@Mark: Nor was it about how an issue (e.g. immigration) was presented.

With respect to you, I disagree, that was the central point of the experiment. The topic of immigration was broached to the experiment subjects immediately after two carefully prepared texts were presented. In my book, that counts as "how immigration was presented." It was presented to the subjects' guts, not their heads.

The experiment was subtle because it was carefully designed to isolate the effects of framing itself, rather than any slogans or explicit argumentation.

But that does not imply that political operatives need to be just as subtle as psych experimenters when making use of this phenomenon. This experiment was subtle, but framing can also be pithy or blunt or direct.

[(myl) That may be what "framing" means to you, but it's not how George Lakoff uses it, or how the authors of this study use it. Lakoff's definition:

Thus (in Lakoff's example) the phrase "tax relief" frames taxation as an affliction.

What's different about the Landau et al. study is that the ideas were evoked by a process that was doubly indirect: airborne bacteria are dangerous, a nation is like a body, immigration is a danger to the nation. Neither of the pieces of the process were individually effective, and the effect was not achieved by describing immigration in language that evoked the metaphor.

This is certainly an example of the metaphorical thinking that Lakoff describes, but the details of the process are different from any example that I've read about before.

You wrote that "This effect is obvious" — maybe to you, but I was surprised by the way the experiment turned out, and so was the commenter before you. In fact, I'd be willing to bet that there are some small variations in procedure that would cause the experiment to fail. (Though such predictions are often wrong — that's why we do experiments.)

You also wrote that "Republicans have been using framing as a political tool for as long as I can remember". This is certainly true, and it's not just Republicans. But I've never heard of any cases where indirect effects of the type used in the experiment are an explicit goal — "Let's have a 'sneeze in your sleeve' campaign, accompanied by a "Get America back on its feet' campaign, because this will make the public worry about illegal immigration". (I suspect that's because it wouldn't work very well, but that's another story.]

J. Goard said,

December 20, 2009 @ 9:56 pm

Let's please be realistic about the relation of this study to Lakoff's grand claims (in his recent political books, that is). The study shows short-term priming of one frame among many. When Mark writes

my reaction is: well sure, but people have presumably reached various personal equilibria, balancing different semantic frames together with explicit reasoning. Landau et al's method temporarily destabilized those equilibria.

This is a world of difference from Lakoff's attribution of left-right politics writ large to a single frame which dominates a person's long-term thinking. Especially as the argument is mostly backed by Lakoff's own intuitions about how most people on the right and left think, with very little sociological research.

A much more plausible accomodation of this study within traditional views of left-right politics would be roughly that: (i) we all have a rich population of embodied semantic frames, plus several modes of explicit reasoning; (ii) these are differently activated at different times; the frames put pressure on one another, such that (usually) none can get too strong; and (iv) regular input from direct self-interest, coalitional alliances, genetic biases, and variation in personal experience, plus chance, causes each of us to reach different equilibria in our default politicial views. This would seem to connect centuries of political thought with lingustic semantics, not overturn it in favor of a single omnibus frame pace Lakoff.

In other words, while the short-term priming of embodied semantic frames are very important for cognitive linguistics, it does not seem to threaten any kind of revolution in political sociology.

[(myl) This analysis makes sense — it's a more coherent expression of how the study struck me — and I certainly don't see the paper as having major implications for political sociology.

But I still think that the results are striking, and I'd like to know how general they are. I doubt that there are any lessons for political operatives, but the experiment does suggest that apparently-unrelated current events might have surprising effects on public opinion. (It also suggests some techniques for exploring the dimensions of political thought, depending on how reliable and general the phenomena are.)

I also thought it was interesting that nobody else (except for the editor of the "Random Samples" section of Science) thought the paper was interesting enough to write about.]

Wednesday Round Up #96 « Neuroanthropology said,

December 30, 2009 @ 8:33 pm

[…] Liberman, Framing a Poll Metaphors are about concepts, not words, and those concepts are embodied. A great new set of […]

This Is Your Brain on Metaphors - NYTimes.com said,

November 14, 2010 @ 5:31 pm

[…] exploiting the brain’s literal-metaphorical confusions about hygiene and health is also shown in a study by Mark Landau and Daniel Sullivan of the University of Kansas and Jeff Greenberg of the University […]

Of metaphors and morals « Essays and Miscellania said,

November 16, 2010 @ 1:20 pm

[…] exploiting the brain’s literal-metaphorical confusions about hygiene and health is also shown in a study by Mark Landau and Daniel Sullivan of the University of Kansas and Jeff Greenberg of the University […]

This Is Your Brain on Metaphors « On the Human said,

December 16, 2010 @ 12:37 pm

[…] exploiting the brain’s literal/metaphorical confusions about hygiene and health is also shown in a study by Mark Landau of the University of Kansas. Subjects either did or didn’t read an article about […]

An Illness Within. | Roi Word said,

June 18, 2012 @ 7:27 am

[…] fascinating study by psychologists Mark Landau, Daniel Sullivan and Jeff Greenberg illustrates this point. Subjects […]