Multiscriptal graffiti in Berlin

« previous post | next post »

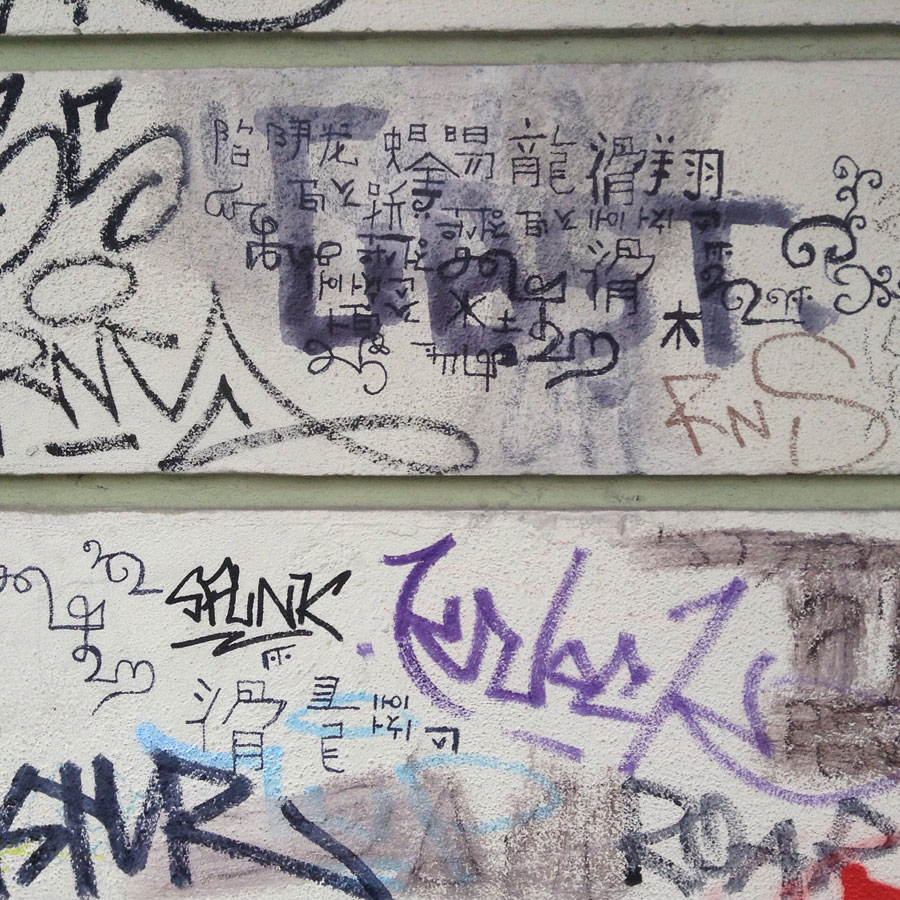

Gábor Ugray took this photo last week outside a Turkish-run Italian restaurant in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district, a diverse mix between run-down and hip:

We have often encountered multiscript writing in East Asia, e.g.,: "Multiscript Taiwan advertisement " (12/28/13). In such instances, the multiple scripts are seamlessly integrated in advertisements, announcements, notes, articles, and so forth for the purpose of conveying a more or less coherent message, i.e., they are reflections of digraphia, trigraphia, and so on — whether emerging or functioning.

This Berlin example is of a different sort. I would put it in the category of practice writing. The author is clearly a novice at Chinese writing, but, at the same time, he / she is intent upon trying to get the strokes and shapes of the characters right.

The most obvious characters that leap off the wall are xiáng huá lóng 翔滑龍, which can actually be read as "soaring, slippery dragon", or, going in the other direction, lóng huá xiáng 龍滑翔 ("the dragon is slippery and soaring"). In part or in whole, these three characters are repeated on the wall, so they seem to form the centerpiece of his / her scribal activity in this iteration. My surmise is that the author is trying to work the phrase up into a signature, and it may also be a tattoo that he / she sports. It is interesting that the artist tries out both the traditional 龍 and the simplified 龙 forms of lóng ("dragon").

Other identifiable characters on the wall are:

mù 木 ("wood")

shuǐ 水 ("water")

tǔ 土 ("earth")

quán 全 ("complete")

yīn 阴 ("shade; femininity")

yáng 暘 ("rising sun; sunshine")

xiàn 陷 ("trap; sink; cave in; sink down")

I think there's little doubt that, aside from the soaring, slippery dragon, another major theme of the artist are the wǔ xíng 五行 ("Five Elements / Five Phases / Five Agents / Five Movements / Five Processes / Five Steps / Five Stages") of Chinese cosmology. These are wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. Wood, water, and earth are clearly present, and it's possible that the quán 全 ("complete") may be a garbled attempt to write jīn 金 ("metal"), and there may even be a huǒ 火 ("fire") lurking in there somewhere.

Complementing the Five Elements / Phases are yīnyáng 阴阳 (trad. 陰陽), the dynamic forces respectively of shade and femininity and of brightness and masculinity. The artist wrote yáng 暘 ("rising sun; sunshine") instead of yáng 陽, but I suppose that he / she meant the latter.

As for the last recognizable character, xiàn 陷 ("trap; sink; cave in; sink down"), this is something that dragons do when they're not soaring.

On the wall, there are also fragments of other characters and characters that are so ill-formed as to be difficult to decipher definitively.

Gábor says that he also espies some Korean Hangul on the wall, as well as:

…a script that looks Indian to me; and one more script, or perhaps just random floral patterns. Plus some usual graffiti noise.

One thing is certain: the artist is working on a number of themes that he / she repeats and develops. While several of these may be purely decorative, some appear to be derived from other scripts. Perhaps Language Log readers will be able to discern what they are.

[Thanks to Fangyi Cheng and Xiuyuan Mi]

Jongseong Park said,

June 30, 2015 @ 9:36 am

There is definitely some attempt to mimic Korean hangul there, but it is much less successful in producing anything that is readable. Both the upper and lower sections have what look like upside-downㅣ처 and ㅣ에 , which is curious because it looks like whoever drew this considered the vertical stroke (which I wrote as the disembodied vowel letter ㅣ) was part of the syllabic unit, which it can't be. There is also something that looks like an upside-down 정 except with extraneous strokes appended (an elongated ㅗ?), though it could be a really badly mangled attempt to produce something like 정신은 with the stroke connections mis-analysed. There are other bits that look sort of like vowel-less combinations of ㄱ and ㅅ. I wonder if whoever did this tried to reproduce something that looked like hangul syllables only from looking at an upside-down text (the Chinese characters are right-side up) and with no knowledge of what makes a well-formed hangul syllable.

Jonathan said,

June 30, 2015 @ 10:08 am

Isn't that Tamil mixed in there?

Keith said,

June 30, 2015 @ 11:30 am

There definitely seem to be some letters from Indic scripts in there, such as ஹ (U+0BB9, Tamil Letter Ha) but with the left-hand half a but rotated to look more like a digit 2. Then again, it could be a Tamil digit 2 followed by a letter Rra ௨ற run together.

Victor Mair said,

June 30, 2015 @ 1:53 pm

From a Korean language teacher:

I am not sure if this person can read/write in Korean or not. All the Korean letters were written upside down and I also see some unconventional letter formation (e.g. 신체에 is written as ㄴ시 ㅣ처ㅣ에 and 깃든 is written as something that looks like 깃문). Maybe this person tried to copy a Hangul phrase in stylish way? I am not sure. Anyways, I read the following phrase:

신 체에 깃든 정신은: (신체 body + 에 (to) + 깃든 (be woven into) + 정신 (mind, soul) + 은 (topic particle)

sinchee gitdeun jeongsineun

shinch'ee gittŭn jŏngshinŭn

A mind/spirit/soul embodied in a body

This phrase seems to be from:

건전 한 신체에 건전한 정신이 깃든다

geonjeonhan sinchee geonjeonhan jeongsini gitdeunda

kŏnjŏnhan shinch'ee gŏnjŏnhan jŏngshini gittŭnda

A sound mind in a sound body

From a colleague who knows Chinese, Japanese, and Korean:

Ha. I see something that people who apparently didn’t know Chinese tried to make look like “Chinese characters”. Same for the “Korean” —except the imitations were even poorer. Looks like the graffiti artists may have been looking at some Korean that was upside down…

All this scribbling reminds me a little of some of the “art” I saw last weekend at the new Whitney Museum of American Art. (The new building is in the meatpacking district on the West Side.) Here’s an image of one of the works exhibited there by that famous pop artist Edward Ruscha:

[[image omitted]]

There were several other such examples of silliness by that “artist”, who seems to have had a certain amount of fascination with “Oriental” writing, but not enough to actually learn any of it.

On a tangent, Victor, I have to admit to being something of what I remember the Germans calling a Kunstbanause—that is, a boor with no appreciation of “Kunst”. But to me, so much—maybe even a majority—of what the Whitney had on display there looked like pure hucksterism to me. I mean, good Lord, I listened in on some of the information the tour guides there were giving their little crowds of listeners, and they were going into raptures about—and I kid you not—what were literally nothing but huge monochrome canvases. One masterpiece was a solid matte black canvas in a black frame; another was solid burnt umber. There was no texture or brush marks; the artists must have used rollers from Home Depot! Nearby masterpieces were like that, too, except for, in one case, a white corner, another had a green stripe. These were apparently priceless treasures! Really, why is the art world such a scam!?!

At least Ruscha was trying to paint something.

Thorin said,

June 30, 2015 @ 4:58 pm

The 2-M figures look like backward versions of the Georgian letters დღ, which make up most of the word for "day". But that's the best I can think of.

maidhc said,

June 30, 2015 @ 5:52 pm

If you live in any kind of a cosmopolitan place, you will constantly encounter signs written in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Hindi, etc. For the average person who doesn't know these languages, it's something you will never be able to understand. It's not like (say) Spanish, where you might be to pick out a few words here and there and eventually figure out what it is they sell in a carnicería. You move through a visual environment where there is information on display that you will never be able to comprehend, because the barriers to comprehension are too high.

As an artist, one might develop an interest in these writing systems just as a design element. They are part of our visual environment just like product trademarks, traffic signs, etc.

Certain types of graffiti are also messages that only certain people can read, such as gang signs. There is a long tradition of this going back to hobo signs. I don't know how much historical awareness there is among the people who put up such graffiti though.

I don't know what's up with this particular example, but it seems to intersect some of these concepts.

Jongseong Park said,

July 1, 2015 @ 2:02 am

A Korean language teacher is right of course that the intended phrase was 신체에 깃든 정신은 sinche-e gitdeun jeongsin-eun—now I see it. It's like that moment when you suddenly recognize that what initially appears to be random blobs actually is a picture of a dalmatian in that optical illusion image.

The first part I saw was the lower part where the 체 was split across different lines as 처 and ㅣ which threw me off, and even when I thought a part looked like 정신은 jeongsin-eun I didn't think to try to find actual phrases that this could be from. I might have caught this if I actually looked at the picture rotated 180 degrees rather than doing this in my head…

Oh, and I'm completely certain that the mangling of the hangul was a result of lack of familiarity with the script and not a deliberate stylistic choice.

nulldev said,

July 1, 2015 @ 6:39 am

Offtopic question:

A German theologian tells me that it is "common knowledge" that "many languages" have no separate word for "woman" (as distinct from "mother", presumably implying marked/unmarked semantics).

Is there even one language for which this is true?

Zeppelin said,

July 1, 2015 @ 10:21 am

nulldev: Not quite the same thing, but in Lithuanian the normal word for "woman" is moteris, (i.e. indo-european "mother", historically), implying that in the past they may have failed to make the distinction. The modern word for "mother" is motina though, so it's unambiguous these days.

In Georgian it's similar, you have the word კაცი k'aci "man, human being", and next to that მამაკაცი mama-k'aci "father-human" =man and დედაკაცი deda-k'aci "mother-human" = woman.

I can't think of a language that habitually fails to distinguish "woman" and "mother", but my horizon is limited to indo-european and some caucasian languages. It's certainly not Common Knowledge among the linguists I hang out with.

David Eddyshaw said,

July 1, 2015 @ 4:53 pm

Greenlandic says "my woman" for "my mother", and indeed "my man" for "my father", using the possessed forms of arnaq "woman" and angut "man."

Even in this case it's not really true that "there is no separate word for woman." The "woman", "man" senses are certainly the primary ones, as is clear from other Eskimo languages.

It may be relevant that Eskimo languages have had a very high rate of turnover in even basic vocabulary, because personal names are often ordinary nouns and traditionally there was a tabu on using the name of a dead person until a child had been born to take over the name again. Meantime the awesome polysynthetic word-formation powers of the language were used to create safe synonyms, and these could end up replacing the original.

In Central Alaskan Yup'ik, for example, the inherited word for "dog" has been replaced by a form which is etymologically "puller."

I hope the German theologian's theology is better than his linguistics.

David Eddyshaw said,

July 1, 2015 @ 5:11 pm

In Albanian, motër, which presumably is derived from the Indoeuropean "mother" etymon, in fact means "sister."

Speculation on how this could possibly have come about it probably bad for the brain, but I suppose an intermediate stage with the meaning "woman" is likely somewhere along the line.

Milan said,

July 2, 2015 @ 2:22 pm

I lived in Southern India for some time, but without really catching on on any of the local languages. However, I´ve got a feeling from the way many people talk when they speak English that there is a tendency in those languages to refer to women with terms referring to gender and marital status, not only to gender. So one might say: "Maidens, wives and widows" instead of just "Women." And, of course, in traditional India being wife usually means being a mother.

However, general words for adult female people, without regard to marital status, certainly do exist and maybe I am just projecting my perceptions about culture unto language.

fisheyed said,

July 5, 2015 @ 1:58 pm

I see ஈ, as well as what looks like ஊ with an extra flourish, as well as the Grantha letters ஹ and ஷ in the second image.

So one might say: "Maidens, wives and widows" instead of just "Women."

I would be fascinated to discover examples of a general audience of women being addressed as "wives and widows". Mothers, sure, but widows? I would be very interested in examples.