So appealing

« previous post | next post »

A few days ago, (someone using the initials) C D C commented:

I get so annoyed when I hear sloppy English on the news.

Today I heard that one of the killers of that soldier in London was going to "appeal his sentence" instead of "appeal against his sentence"!

This was a free-floating peeve, completely unrelated to the content of the post ("The case of the persevering pedestrian", 4/7/2014) or to any of the previous comments — C D C apparently mis-interpreted our discussion of grammatical analysis as one of those articles meant to stir up "Angry linguistic mobs with torches" that the media, especially in Britain, features from time to time.

And as usual for peevers, C D C was not at all curious about the nature and history of the usage in question, and was therefore soon exposed as ignorant as well as intolerant.

As I and others pointed out in subsequent comments, "appeal his sentence" is the normal way to express this concept in American English. Thus in the NYT since 1/1/2000, I counted

| "appeal the sentence" | 86 |

| "appeal his sentence" | 31 |

| "appeal her sentence" | 1 |

| "appeal against the sentence" | 0 |

| "appeal against his sentence" | 0 |

| "appeal against her sentence" | 0 |

And in the Washington Post:

| "appeal the sentence" | 70 |

| "appeal his sentence" | 44 |

| "appeal her sentence" | 2 |

| "appeal against the sentence" | 2 |

| "appeal against his sentence" | 0 |

| "appeal against her sentence" | 0 |

(One of the WaPo's two "appeal against the sentence" usages is in a reprint of a Reuters wire story about a German case, written by a British journalist; the other one is in an opinion piece written by a Kenyan journalist.)

In contrast, the counts for the same period from The Times of London are:

| "appeal the sentence" | 27 |

| "appeal his sentence" | 7 |

| "appeal her sentence" | 2 |

| "appeal against the sentence" | 111 |

| "appeal against his sentence" | 49 |

| "appeal against her sentence" | 15 |

And in the Telegraph:

| "appeal the sentence" | 38 |

| "appeal his sentence" | 14 |

| "appeal her sentence" | 2 |

| "appeal against the sentence" | 61 |

| "appeal against his sentence" | 33 |

| "appeal against her sentence" | 15 |

Thus elite British usage, pace C D C, is mixed, though favoring against, while elite American usage seems to be uniformly against against.

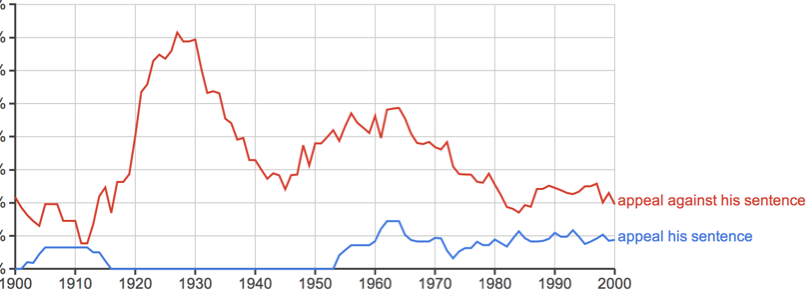

Plots from the Google Books ngram viewer suggest that

- American usage of "appeal against <SENTENCE>", never high, has recently declined;

- British books have been using "appeal <SENTENCE>" for a long time, although at a lower rate than "appeal against <SENTENCE>".

| American English: |  |

| British English: |  |

(There are all the usual reasons to take such inferences and the plots themselves with a large grain of salt — for example, American authors and quotations from American sources are published in Britain, and vice versa.)

In any case, there's clearly a trans-Atlantic difference. And even in British English, the OED indicates that the pattern "appeal <SOMETHING> to <HIGHER_AUTHORITY>" goes back to 1481, and continues at least through 1900:

1481 Caxton tr. Hist. Reynard Fox (1970) 71, I appele this mater in to the court to fore our lord the kyng.

a1593 Marlowe Tragicall Hist. Faustus (1604) sig. A2, To patient Judgements we appeale our plaude.

1900 Westm. Gaz. 22 Aug. 2/2 Possibly the case will be appealed.

The American usage appears in the 19th century, continuing to the present day:

1828 Webster Amer. Dict. Eng. Lang. (at cited word), We say the cause was appealed before or after trial.

1870 J. R. Lowell Among my Bks. (1873) 1st Ser. 178 To appeal a case of taste to a court of final judicature.

1932 E. Wilson Devil take Hindmost xvii. 192 The defense will appeal the case to the Supreme Court.

So perhaps the American "appeal his sentence" usage continues the original British tradition, and the British "appeal against his sentence" usage is an innovation of the past century.

If so, then C D C would not even have the excuse of complaining about an Americanism — the "sloppy English" in question is actually traditional English, as established by Caxton and Marlowe, before the reckless linguistic innovation of 20th-century British jurists.

GeorgeW said,

April 13, 2014 @ 10:10 am

I must confess (SoAmE) that I don't recall ever encountering "appeal against." However, I am sure I must have and just dismissed it as quaint Britishism. But, apparently, it is not even quaint.

CuConnachit said,

April 13, 2014 @ 10:36 am

I was once taught that the only proper form was "appeal from" (the sentence/verdict, etc).

Peter Taylor said,

April 13, 2014 @ 10:36 am

I don't quite see the relevance of the six citations from the OED. The four distinct words which are the direct object of appeal (mater, plaude, case, and cause) in these citations are roughly synonymous, and they refer to the legal proceeding or the subject of dispute. "Appeal against his/her case" has a grand total of 10 Google hits, vs about a million for "Appeal against his/her sentence".

It would be far more convincing to cite examples of appealing the outcome, judgement, result, conviction, or acquittal, which share a similar position to sentence in being the product of that legal proceeding.

[(myl) The first step is that there's a 500-year-old transitive usage, in which the object of "appeal" is a legal matter. This much the next two commenters falsely deny. Then there's the valid question you raise, of when and where the object of appeal came to be be an outcome, verdict, judgment, sentence, etc. It's clear that this has been normal in American usage at least since the middle of the last century. While British writers seem more often to use "appeal against" or "appeal from", plain transitive appeal has been used with "sentence" as an object on and off in British newspapers for quite a while (though generally in describing legal affairs outside of England), e.g.

The Attorney General's spokesman said a decision on whether or not to appeal the sentence would be made 'urgently'. [Belfast Telegraph a1990, from BNC]

Irving's lawyer Elmar Kresbach immediately announced he would appeal the sentence. [The Guardian 2/20/2006]

Dutt's lawyers announced today they will appeal the sentence to India's supreme court. [Telegraph, 7/31/2007]

He explained that the prosecution must base any appeal on the legal reasoning of the verdict. It may not appeal the sentence in and of itself. [Telegraph 1/18/2011]

We live in a bankrupt state that pays the political authors of our misfortunes annual pensions of €150,000; the biggest processor in our beef industry still cannot explain how horse meat got into his beef burgers; a local council wants to introduce special permits that would allow rural dwellers to drink and drive; a senator reveals he tries to avoid getting into a taxi in Ireland if it is driven by a foreigner; one of the country’s leading judges gives bail to a sex offender, who admitted raping his daughter over a 10-year period, in the expectation that somebody might appeal the sentence. [Sunday Times 1/27/2013]

The New South Wales director of public prosecutions will appeal the sentence handed to Kieran Loveridge for the death of Thomas Kelly, on the grounds that it is manifestly inadequate. [The Guardian 11/14/2013]

]

chris y said,

April 13, 2014 @ 10:50 am

As a native speaker of British English, I regard "appeal" as an intransitive verb in any context. I am also aware that this isn't the case in American English, which is just one of those things. If I were a pedant, I would correct a British writer for using it transitively, but not an American. Since I'm not, I honestly don't care.

Stephen said,

April 13, 2014 @ 11:10 am

As a BrE speaker in his 50s 'appeal his sentence' sounds totally wrong.

You 'appeal to' someone (e.g. a judge for mercy) or you 'appeal against' something (e.g. a verdict, sentence or both).

Echoing Peter Taylor, I don't think the OED citations support the point made. The first two are, IMO, examples of 'appeal to' someone.

In the third appeal is, it seems to me, being used in a different manner. I think that appeal here is a contraction of 'lodge an appeal', with the necessary restructuring needed after that contraction.

Viseguy said,

April 13, 2014 @ 6:45 pm

For what it's worth, the normal usage among New York lawyers is "appeal from". Also, as a matter of interest to NY lawyers (and probably nobody else), the only juridical acts that are appealable as a matter of state practice are judgments and orders. You can't appeal a decision, verdict, or sentence per se. An appeal from a judgment or order "brings up for review" the decision leading to (or constituting) the order, the verdict underlying the judgment (to the extent, often limited or nonexistent, that the appellate court has the power to review factual determinations), the sentence imposed (which is part of the final judgment in a criminal case), etc., etc.

David Morris said,

April 13, 2014 @ 7:42 pm

In Australia's two most populous states, at least, the official terminology is 'appeal against conviction/sentence' and 'appeal to [a higher court]'. Transitive 'appeal' is used by the media. I noticed one instance last week regarding a recent high-profile case. To me (last 40-ish, AusEng speaker), 'appeal' is intransitive. 'Appeal the sentence' is as 'wrong' as 'appeal the judge'.

D.O. said,

April 13, 2014 @ 7:42 pm

As an avowed non-linguist and non-lawyer, it seems to me reasonable to consult formal legal documents from which lawyers take their language, then reporters learn from lawyers, and the public follows the press. A search of the US Code shows 224 instances of "appeal the" (actually, not instances, but sections) some of which are spurious, but most are real. For example, 8 USC 1228 (c )(3)(iii) "Upon execution by the defendant of a valid waiver of the right to appeal the conviction on which the order of removal is based, etc." "Appeal from" finds 202 instances, but some of them are nouns. So, roughly speaking, it's a mixed bag.

QuiteContrary said,

April 13, 2014 @ 8:20 pm

Viseguy, here's a counter-example from the New York Court of Appeals in January:

"Defendant timely appealed the resentence and was assigned counsel, who reviewed the file…" https://www.nycourts.gov/ctapps/Decisions/2014/Jan14/SSM27opn14-Decision.pdf

(But I think that's atypical for the Court of Appeals; they're generally more precise in their wording.)

I'm actually not so sure we take particular care in ordinary conversation to refer precisely and correctly to "the order [or judgment] appealed from" or "an appeal from the order [or judgment]"… But I'm curious now, and will certainly start listening more closely from now on.

A bit of a tangent, but the verbal quirk that stood out for me when I was first admitted to practice was that everyone would say that Lawyer X "is on trial." (E.g., I can't do a conference call next week, I'm on trial.) To me, this always sounded like Lawyer X was being tried for a crime (as a defendant), although in context it was clear that Lawyer X must be appearing at the trial in a representative capacity… Is this usage specific to lawyers in NYC? I don't know, but would be curious to hear from attorneys in other states or upstate New York.

Mark Liberman said,

April 13, 2014 @ 9:29 pm

A quick search of California's state codes turns up many examples of transitive appeal where the direct object is an outcome, e.g.

The applicant or other affected person may appeal the decision.

If the person upon whom the sealer levied a civil penalty requested and appeared at a hearing, the person may appeal the sealer’s decision to the secretary within 30 days of the date of receiving a copy of the sealer’s decision.

A license of a licensee or a certificate of a registrant shall be suspended automatically during any time that the licensee or registrant is incarcerated after conviction of a felony, regardless of whether the conviction has been appealed.

The city may appeal any measures or fees imposed by the district to the state board within 30 days of the adoption of the measures or fees.

An applicant or licensee may appeal the commission’s denial, suspension, or revocation of a license under this section.

However, if consent is withheld, any party may appeal the withholding of consent to the board, which may determine that consent is not required.

For purposes of this section, “to advocate for medically appropriate health care” means to appeal a payor’s decision to deny payment for a service pursuant to the reasonable grievance or appeal procedure established by a medical group, independent practice association, preferred provider organization, foundation, hospital medical staff and governing body

Viseguy said,

April 13, 2014 @ 10:44 pm

@QuiteContrary ("here's a counter-example from the New York Court of Appeals in January"):

The procedural distinction between judgments/orders and everything else is, granted, a precept more honored in the breach, even among judges and lawyers, and even, no doubt, in judicial opinions. It's the kind of esoteric rule that court clerks thrive on, and that everyone else more or less ignores. But I got my start, 36 years ago, as an Appellate Division clerk, so the distinction was seared on my brain at an impressionable age.

Neal Goldfarb said,

April 13, 2014 @ 11:34 pm

@QuiteContrary:

Down here in D.C., when a lawyer is trying a case as counsel, as opposed to being tried as a defendant, we say that they are "in trial."

Chris said,

April 14, 2014 @ 2:48 am

In Britain in the mid-20th century, "appeal" was exclusively intransitive. Anyone heard using it transitively would immediately have been recognised as American. As Prof. Liberman shows, things are different now, and young journalists even on conservative papers such as the Times and the Telegraph have adopted the American style. But to an older Brit like me that usage still jars.

Andrew McCarthy said,

April 14, 2014 @ 2:49 am

I am inclined to suspect that "appeal against" in BrE is, like so many pieces of English-language legal jargon, a Frenchism deriving from the use of Law French in medieval English courts.

In French the verb "appeler" usually means "to call," but "faire appel" means "to appeal" in the legal sense. The most commonly used phrasing, judging by Google, is "faire appel du jugement" (to make an appeal of the verdict) but "faire appel contre le jugement" is also fairly frequent, if less common.

It also seems to me that French generally inserts prepositions between verbs and their predicate nouns more often than English does. For example, you don't telephone John, you telephone to him.

Andrew McCarthy said,

April 14, 2014 @ 2:52 am

Forgive my misuse of the term "predicate noun" in the above post–it's 3 AM and I'm tired. I obviously meant the object of an action verb.

Martin said,

April 14, 2014 @ 5:43 am

@QuiteContrary Australian lawyers, at least, will say "I did my first murder at 25…" and the like (Sydney Morning Herald?)

Phil Jennings said,

April 14, 2014 @ 6:41 am

The British go around agreeing things instead of agreeing on things or agreeing about things. Two can play at this game. Hah.

Terry Collmann said,

April 14, 2014 @ 8:09 am

My job these days involves a great deal of reading regional/local British newspapers, and my impression is that "appeal the sentence" and the like would have been non-existent in British journalism in my own youth (I'm 61) but is certainly becoming increasingly common in British newspapers generally today: I don't think this is the "recency illusion" on my part, but a genuine move by young Britons towards the American usage. Why, however, I can't imagine: I would have thought that young British journalists today would have been just as much or more exposed to the older British "appeal against" in their reading than to the simpler American form, and I have not noticed any increase in other American forms, e.g. British newspapers saying "write your MP" instead of "write to your MP".

un malpaso said,

April 14, 2014 @ 8:53 am

I have never once heard "appeal against…" used in this context… only "appeal". This is truly a strange peeve. Maybe it's my USA-ness?

Eric P Smith said,

April 14, 2014 @ 9:57 am

@Terry Collmann: I would guess that young British journalists are drawn to "appeal the sentence" rather than "appeal against the sentence" because it is shorter and sounds snappier. They are less likely to abandon "write to your MP" because the latter construction is everyday English in the UK.

Eric P Smith said,

April 14, 2014 @ 10:02 am

I should like to thank C D C for his (or her) comment. Yes, he was mistaken, and he appears to be unfashionably prescriptivist. But he loves his language, and he cares about correct and incorrect usage, and he is genuine and not a troll (so far as I can judge), and he has triggered a fascinating discussion.

Treesong said,

April 14, 2014 @ 10:12 am

@QuiteContrary,Neil Goldfarb: perhaps

NYC – be on trial, stand on line

rest of universe – be in trial, stand in line

?

Lauren said,

April 14, 2014 @ 10:55 am

Well, it seems like the Center For Disease Control's apparent error was simply in not knowing that American English had different standards for that construction. In my experience it's quite a common thing to mistake an unusual phrasing for a simple grammatical error, only to later have it turn out to be perfectly normal in a different dialect (American vs. British English especially), so perhaps it's not quite so ignorant. I've been both the accused and the accuser in that kind of situation.

Brett said,

April 14, 2014 @ 11:02 am

"Write to your Senator" is everyday American English as well. It's probably more common than "Write your Senator." There is probably minimal pressure to change the usage pattern when the one used in Britain is also unremarkable in America.

Keith M Ellis said,

April 14, 2014 @ 3:22 pm

There's implicitly a larger discussion here, that of descriptivism versus prescriptivism with regard to technical language vis a vis popular usage.

Personally, I find that a principle of moderation is useful here, as it so often is in these arguments about prescriptivism/descriptivism. After all, we descriptivists entirely agree with the prescriptivists about "appropriateness", which they confuse with "correctness". They tend to argue as if the descriptivist position is one that disregards register and "standards" when, of course, this isn't true at all. We're all using standard written English here, more or less.

So my view is that to the degree to which a usage occurs within a technical context, is the degree to which a usage ought to conform to that technical meaning and convention. While sometimes this context is entirely unambiguous, such as within a court judgment or a scientific paper, very often the context is something that straddles the technical and popular worlds — this is especially true in journalism, where a story may be written for a popular audience about a technical subject. And doubly so when it's only incidentally about a technical subject (as opposed to primarily).

Per the above comments, I'm unclear on whether there's within even the limited American or British contexts some judicial standard on the technical usage of appeal [against] the sentence. But even supposing there is, it's unclear whether casual, common speech or journalistic usage should be strictly limited to the technical.

Similarly, while I am fascinated by Pullum's and (less frequent) Liberman's complaints against the supposed misuse of passive voice, I'm inclined to see this as special pleading by linguists, defending a prescriptivism about popular (mis)use of a technical term within their bailiwick — a defense they don't allow many others with similar concerns.

Granted, my rule-of-thumb is to ask just how very specifically is this popular usage intended to conform to the technical usage (or, alternatively, how much does the speaker seem to believe that they are speaking technically), and by that standard passive voice by writers about language, albeit non-linguists journalists, seem to be pretending to be writing authoritatively about a technical subject. So in many of these examples, I agree with the criticism.

In this case, though, there very much does seem to be a popular discussion about legal proceedings that involve a vague, largely uninformed notion about the law, strongly influenced by popular fictional narratives, which may mimic technical usage in some respects, but is otherwise independent. If so, then it matters very little what the technical usages are; how regular people discuss legal appeals is largely a matter of popular convention, full stop. And so there can be no refuge from the usual descriptivist analysis.

Levantine said,

April 14, 2014 @ 3:40 pm

Phil Jennings, I'm British, and I'm not familiar with the construction you're referring to. Can you give an example?

Levantine said,

April 14, 2014 @ 4:57 pm

Sorry, an example just came to mind: "They agreed a compromise."

D.O. said,

April 14, 2014 @ 6:47 pm

@Keith M Ellis. I think the situation is more complicated here. Expression "appeal (against, from) the conviction" does not exist outside the legal context. Natural conjecture, then would be that official usage from legislatures and the courts will influence usage downstream by lawyers, journalists, and the public. Apparently, this is not the case. In AmE official usage is mixed, but journalistic is (almost) exclusively transitive and in BrE official usage is exclusively intransitive, but journalistic is mixed. Maybe it means that "natural pull" of the language is to the intransitive usage, but that officialdom for some (maybe, very good) reason decided that intransitive is more appropriate. Of course, that's a pure speculation…

Lindsay Costelloe said,

April 14, 2014 @ 6:58 pm

As an older Australian, I am most used to "appeal against the sentence/conviction" as David Morris mentions. It does seem, also as DM says that journalists are using the American transitive form more frequently. I think that this parallels the usage of "protest" versus "protest against", the latter of which I was most used to hearing in the past, but which is being supplanted by the transitive form.

What fascinates me about these two usages is that they seem to run contrary to patterns of usage in AmE and BrE where AmE favours more phrasal verbs. I am old enough to recall the first time I heard an Australian say "listen up" as opposed to "listen", and "meet up with" rather than "meet". I even hear them on British TV shows now.

Viseguy said,

April 14, 2014 @ 7:26 pm

If you want a phrasal verb for "appeal", New York lawyers have one: "take (it) up". As when a lawyer says to his or her adversary, "If you don't like the judge's ruling, take it up!" ("… on appeal" being understood).

Eric P Smith said,

April 14, 2014 @ 7:37 pm

@Lindsay Costelloe: I'm not sure that "appeal the conviction" runs contrary to AmE favouring phrasal verbs. As I understand it, a phrasal verb is a verb + preposition acting as a syntactic constituent (on one theory) or acting as a semantic unit (on another theory). "Listen up" and "meet up with" would be classed as phrasal verbs by those who admit the concept. But in "appeal against the conviction", "against the conviction" is a straightforward prepositional phrase: there is no phrasal verb.

chris said,

April 14, 2014 @ 8:06 pm

I thought one of the distinguishing characteristics of phrasal verbs was the following difference in word order:

I heard a word I didn't know, so I looked it up.

When I chased the cat around the corner, I found a staircase, so I looked up it.

Only a true phrasal verb allows postponing the "preposition"; "I looked the staircase up" suggests that you're consulting a blueprint or something.

Of course this is not much help with "listen up", which is intransitive. But it suggests that "meet up with" doesn't qualify: "with" is acting as an ordinary preposition and refuses to be moved after its object. "I met up Jim with" and "I met Jim up with" would rarely, if ever, be uttered by a native speaker of any dialect of English I am aware of.

P.S. In some cases the postponement seems practically mandatory: nobody would climb the Top 40 with "I'm Gonna Knock Out You".

David Morris said,

April 15, 2014 @ 5:50 am

Rickroll! Never gonna give up you …

Lindsay Costelloe said,

April 15, 2014 @ 9:24 am

Looks like a terminological snafu on my part. The observations on usage in my experience still stand, though.

Ted said,

April 16, 2014 @ 1:37 pm

I think the technical "appeal from a judgment of conviction" becomes the colloquial "appeal the conviction." Which, technically, requires a petition to have the judgment reversed.

Someone more learned than I will have to enlighten me on when, if ever, it might be correct to say that a judgment is overturned rather than reversed.

Adrian said,

April 17, 2014 @ 8:19 am

I have noticed this recent change in British news media towards using appeal/protest without "against", i.e. adopting the American usage, and assumed that editors have decided it's one way they can make their output more uniform, since English-language journalism is becoming more transatlantic. Of course, it also saves time and space.

James Wimberley said,

April 17, 2014 @ 1:26 pm

Like many English legal terms, the word comes from the French, viz. modern appel (n), appeler (vt). Although the verb is transitive, the object is a person, the police, etc, not a court or decision. Current French has appeler d'un jugement / d'une sentence. Can anybody shed light on whether usage was different in 1200 in Norman and Angevin courts?

ohwilleke said,

April 21, 2014 @ 4:04 pm

"appeal the sentence" isn't really sloppy. Indeed, the phrase is more specific, as one is making clear by saying so that the conviction itself is not disputed, just the sentence imposed as a result of the conviction. In that context, sloppy would be simply saying "he will appeal the decision."

Rather than being sloppy, this is more of an omission of words that are necessarily implied "appeal [the portion of the judgment in the criminal case setting] the sentence [but not the conviction]", because a sentence can't be imposed in the absence of a judgment of conviction together with a sentence imposed in connection with that conviction.

I have never seen the phrase "appeal against" in American legal usage, even in obscure English cases from law school.

J. W. Brewer said,

April 21, 2014 @ 5:36 pm

This is late, but is there any evidence of this usage of "appeal against" (as distinguished from "appeal from") in "official" AmEng legalese usage within the last century or so? Some casual and non-exhaustive googling on my part turned up only false positives, where the object of "against" was not the decision/order/whatever of the lower court, but the opposing party to the dispute, e.g. (from a 1964 dissent from denial of cert. written by Mr. Justice Black) "The natural defensive step for Bertman to take then was to file a notice of appeal against Kirsch, but notice of the Government's appeal was not served on Bertman until after the 60 days had passed—too late, both courts below held, for Bertman to take his appeal." You can see this same (quite different imho from the BrEng phenomenon at issue) usage in journalese as well, e.g. "ZapMedia Loses Appeal Against Apple in Patent Infringement Lawsuit."