High-altitude ejectives

« previous post | next post »

Caleb Everett, "Evidence for Direct Geographic Influences on Linguistic Sounds: The Case of Ejectives", PLoS ONE, 2013:

We examined the geographic coordinates and elevations of 567 language locations represented in a worldwide phonetic database. Languages with phonemic ejective consonants were found to occur closer to inhabitable regions of high elevation, when contrasted to languages without this class of sounds. In addition, the mean and median elevations of the locations of languages with ejectives were found to be comparatively high.

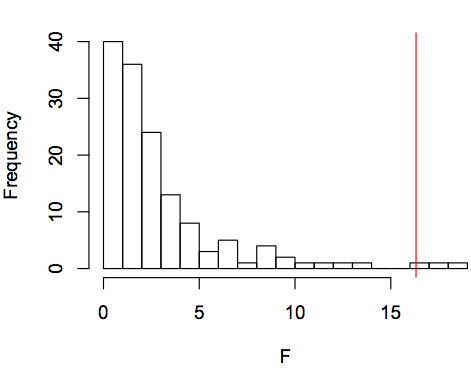

Sean Roberts does some of the statistical checks that Everett should have done and didn't ("Altitude and Ejectives: Hypotheses up in the air", replicated typo 6/13/2013), and the connection between altitude and ejectives hold up fairly well. Thus only two linguistic variables ( Order of Object and Verb and the Relationship between the Order of Object and Verb and the Order of Adjective and Noun) have a stronger connection with altitude than the ejectives feature (red vertical line) does:

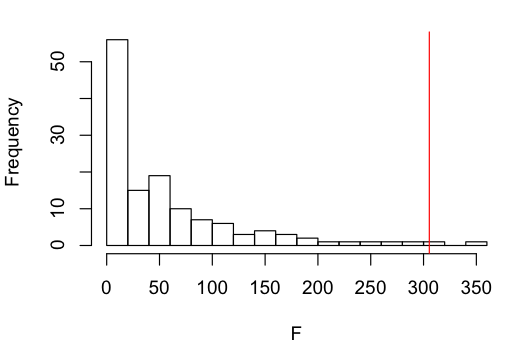

In comparison, here's Sean's check on Keith Chen's association of the future-tense variable with savings rates ("Whorfian economics reconsidered: Residuals and Causal Graphs", 2/28/2013):

Still, the (presumably) spurious correlations of the two word-order variables with altitude remind us of the possibility for false findings here. Some past posts on similar issues from the same source: "Most important paper on cultural evolution that includes acacia trees published", 1/17/2013; "Spurious correlation bonanza to mark Replicated Typo 2.0 reaching 100,000 hits", 11/30/2011; and a published paper, Sean Roberts and James Winters, "Social Structure and Language Structure: The New Nomothetic Approach", Psychology of Language and Communication 2012.

Whether or not the altitude/ejective correlation reveals a causal connection, we can expect the near future to bring us a large number of spurious correlational analyses, along with a few meaningful ones. There are three reasons for this:

(1) The existence of digital datasets makes it increasingly easy to perform quantitative checks on hypotheses about possible relationships between linguistic and non-linguistic variables;

(2) The astronomically large number of such possible relationships guarantees that many of them should exhibit a strong pair-wise connection by chance, even if all of the distributions were statistically independent;

(3) The distributions are not statistically independent, due to factors such as cultural and geographical diffusion.

Note that the "file drawer effect" strongly undermines the often-made argument "But I/we made the hypothesis before we checked, we didn't just dredge for correlations and then try to explain them". The data-dredging (and the associated multiple comparisons) can (and do) occur across many unconnected investigations, with only the "significant" ones getting published.

As a result, responsible journal editors ought to insist on at least one simple thing: comparison of the asserted relationship with the full distribution of logically-possible relationships in the dataset(s) being analyzed. This check was absent from Everett's paper, but was supplied by Sean Roberts with a few minutes of work done while waiting for a plane in Singapore airport.

But in every pair of datasets, for each variable in one of the datasets, we'll see a distribution like those shown in the plots above, showing an especially strong statistical connection to a few of the variables in the other dataset. And sometimes these connections won't make any sense — verb-object order and altitude, or velar nasals and savings rates, or lexical tone and acacia trees — while others will suggest a plausible causal story in one direction or the other — ejectives and altitude, future tense and savings rate, or lexical tone and haplogroups of ASPM and MCPH. So plots of this kind doesn't guarantee that the connections in the high-significance tails are directly meaningful ones. Still, it's a start.

A pioneering (and plausible) effort to correlate linguistic and geographical variables was John Fought et al., "Sonority and Climate in a World Sample of Language: Findings and Prospects", Cross-Cultural Research 2004:

In a world sample (N = 60), the indigenous languages of tropical and subtropical climates in contrast to the languages spoken in temperate and cold zones manifested high levels of sonority. High sonority in phonetic segments, as found for example in vowels (versus consonants), increases the carrying power of speech sounds and, hence, audibility at a distance. We assume that in the course of daily activities, the speakers in warm/hot climates (a) are often outdoors due to equable ambient temperatures, (b) thereby frequently transmit messages distally, and (c) transmit such messages relatively intelligibly due to the acoustic and functional advantages of high sonority.

But Fought et al. had to do a lot more work to test their hypothesis than they could have managed while waiting for a plane at Singapore Airport. They started by choosing a sample of 60 societies from the HRAF Probability Sample Files, geographically stratified and "chosen to represent the 60 macrocultural areas of the world". Then they had to devise and implement a method for coding these societies for "climate"; and they also had obtain a 200-word vocabulary for each society's language, and to devise and implement a method for coding "sonority" in the pronunciations of those words. Both of these involved extensive expert re-interpretation of previous literature.

In contrast, a decade later, many relevant linguistic and non-linguistic datasets are now pre-compiled and available for easy download, and the software needed for fitting various sorts of statistical models can easily be run on your laptop. So if you have a bright idea — maybe alcohol consumption correlates with phonotactic complexity? really, it could — the chances are that you test a model within a few hours. If it doesn't work out, there are plenty more to try — maybe coffee consumption helps to preserve morphological inflection?

Some previous Language Log discussions of similar things: "Corpus-Wide Association Studies", 3/11/2012; "Cultural Diffusion and the Whorfian Hypothesis", 2/12/2012; "Typological progress", 5/11/2008; "Dediu and Ladd again", 5/30/2007.

Also, everyone should be aware of the path-breaking work on this topic by Mark Dingemanse, "The Hidbap language of PNG", 5/7/2008:

Mt. Iso in PNG, 12 miles southwest of Sumo, east of the Catalina River. Diuwe is spoken between sea level and the first isoline at 100m, Hidbap between the first and the second isolines.

This week, the language of the week at Anggarrgoon is DIY, also known as Diuwe. Claire Bowern, noting that the only comment in the Ethnologue entry of the language is the terse and rather mysterious ‘Below 100 meters’, claims that the phonology of DIY shows an effect of altitude on air stream mechanisms. I thought I would shed some light on this curious situation by profiling Hidbap, a language related to Diuwe.

Hidbap is Diuwe’s closest neighbour both geographically and phylogenetically. It is a language spoken above 100m but below 200m in the same area as Diuwe, that is, 12 miles southwest of Sumo, east of the Catalina River. Like Diuwe, it has exactly 100 speakers. The languages are quite closely related, though there is no mutual intelligibility due to the presence of a large bundle of isoglosses at the 100m isoline. Speakers of either language avoid crossing into each other’s territories at all cost (see below).

Sean Roberts said,

June 14, 2013 @ 10:22 am

Thanks for the links! I agree that we're at a potentially dangerous period where large-scale statistics are easy to perform, but not widely understood. I think there's another factor, though – the pressure for studies to have wider impact and to engage with the general public. While this is generally a good thing, it does tempt authors to explicitly extend their findings to aspects such as public policy, even when the extension might not be warranted. For example, a recent working paper shows a link between linguistic gender systems and female economic and political empowerment (see here). The authors suggest that :

"The direct and possibly cognitive influence of a language on its speakers and on economic life may have important policy implications. For instance, understanding this connection would facilitate the debate regarding the need to implement quotas or to opt for market forces to drive women economic participation up and thereby increase overall economic prosperity."

This kind of generalisation goes too far, in my opinion, given the weak explanatory power that this kind of study has.

Daniel Ezra Johnson said,

June 14, 2013 @ 11:25 am

"The force required to produce [an idealized ejective] gesture at 2500 m would be roughly 26% less than the force required at sea level."

Possible objection: "The salience of [the] burst of air would be reduced in cases of lower atmospheric air pressure… [The] lower pressure differential would…make ejectives easier to produce but also less perceptually salient at higher altitudes."

Supposed counter-argument: "Given that one of the key acoustic characteristics of ejectives is their impact on the acoustic structure of adjacent vowels, it seems quite possible that they are preponderant at high altitudes due in part to articulatory ease, even though lower atmospheric pressure might reduce the salience of their associated burst of air."

OK, so why don't the people at sea level just make an ejective with 26% less compression, 26% less effort, 26% less air burst, and apparently still perfectly distinguishable effects on neighboring vowels?

Caleb said,

June 14, 2013 @ 11:50 am

Hey guys,

Author here. Thanks to Mark and Sean for bringing up these points, which are not entirely unexpected in the light of previous discussions of "spurious correlations", but are well taken nonetheless. Sean's analysis of the data is interesting, and I'm pleased though not surprised to see that my claim regarding absolute elevation holds up. I am surprised though that you both chose to focus on that, rather than the main variable I claim to be central in my article–distance from high elevation zones. (I mention why these data are more reliable in the article.) I just want to be clear that the word order relationship doesn't hold up in the same manner for the distance variable.

While I recognize that this will only get me so far with some (as Mark alluded to), let me be clear: I went looking for this correlation only after basic physical modeling of the vocal tract led me to it. And unlike some of the other correlations out there, this at least has some plausible physical motivations that can be tested. I hope others will in fact test them, just as I hope others reanalyze the distribution of the data points in ways more refined than I did or than Sean hurriedly did.

Admittedly, I didn't expect this to blow up quite like this, given that this was somewhat of a side-project of mine. (Most of my work relates to language and cognition.) The media interest I'm getting is a bit surprising, and please don't hold me responsible for some of the off-base media reports I've seen. I should mention that one of the recurring questions I've gotten from interviewers is something along the lines of, "how have linguists missed this before?" (The association between altitude and ejectives is there after all, whether one thinks it's historical accident or not. The exceptionless distribution of clusters of languages with ejectives in high elevation zones goes unmentioned by you both.) Any thoughts? Is it because many of the languages in question are on plateaus?

Thanks again for your thoughts, and for Sean's reanalysis. For those of you who remain skeptical, my only hope is that you actually read the entire article. If the motivations I suggest for the association turn out to be wrong after future experimentation, so be it. But unlike some other correlations, there are in fact testable physiologically grounded motivations suggested in this case.

Best, Caleb

Kenny Easwaran said,

June 14, 2013 @ 1:08 pm

The rise of big data in linguistics makes Ioannides et al. on medicine quite relevant: http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124

Sean Roberts said,

June 14, 2013 @ 1:58 pm

Hi,

Yes, I should have been clearer in my response: The study differs from many others in that the proposed mechanism behind the link is explicit and precise, and it doesn't directly involve social variables that are attached to values that have the potential to be re-interpreted in ways that might suit particular political or ideological agendas (as opposed to studies that consider economic or political variables).

However, I think the media interest in this study is of the same kind as the media interest in the studies on economics and future tense or chocolate consumption and IQ. Perhaps because there's a perception of these studies as involving an 'eureka' moment where a mystery is resolved, and that anyone could have discovered it. The temptation for onlookers is to go hunting for these relationships for the sake of discovery, sort of like amateur fossil collectors in the early days of palaeontology. As Hay & Bauer state in their 2007 paper "We couldn't resist checking this apparent link … the correlation seemed intriguing enough that it was worth simply publishing the result." I worry that this temptation could lead to less well motivated studies being published.

I think, for many studies of correlations between cultural phenomena, applying a wide battery of tests to a hypothesis is a good idea, and some explicit control for common descent should be included (I should have used the distance from high-altitude regions, though, and I didn't control for geographic relatedness). I guess the main point of my post was to show that this kind of analysis was relatively easy to perform, so there's no excuse not to do it. On the other hand, the factors that make large-scale statistical tests possible also allow other researchers to rapidly engage with the data and analyses – I know that several others have been looking into the statistics – so maybe the model of a single publication that covers all bases is becoming less effective.

I think it's obvious that environmental features affect language evolution, and this paper is a really interesting case study. It's certainly shown that geographic features should be controlled for when doing typological studies. As Everett has pointed out above – this hypothesis can be tested by more direct experiments, and I'll be interested to see what transpires.

Andrew McKenzie said,

June 14, 2013 @ 2:44 pm

Caleb, since you're here: I was curious about the definition of "high-altitude" in this article as being within 200km of a 1500m or higher zone. What led you to select that distance? It leaves a lot of room for languages with ejectives spoken far lower than 1500m— for one thing, almost every cluster is within 200 km of sea level or lower.

Looking at the table of ejective languages you provided, I find that 78% of them are spoken under 1500m altitude… most of them well under it.

So my question about your 'derivation' is: I can see why you'd suggest an evolutionary account of ejective use in high altitudes, but how would an air-pressure difference at altitude have an effect on language speakers 200 km away?

Daniel Barkalow said,

June 14, 2013 @ 4:46 pm

It seems to me that comparative linguistics is direly in need of an equivalent to Bennett, Baird, Miller, and Wolford 2010. Unfortunately, it's hard to come up with anything in linguistics quite as picturesque as the brain activity of a dead fish. Or, for that matter, anything crazy that people won't tend to believe is actually true.

marie-lucie said,

June 14, 2013 @ 9:44 pm

Languages are not totally independent entities but most of them are part of genetically related groups (within the linguistic definition of "genetic" and "related"). If location, especially altitude, influences phonology and especially the presence/development/disappearance of certain consonants (still an undemonstrated hypothesis at this time), then one would expect not just differences but gradients within language families where several related languages are spoken at different altitudes, with the higher ones more likely to include ejective consonants, or more of them than at lower altitudes (many languages have ejective stops, a few more also have ejective affricates, and only a few also have ejective fricatives).

Another problem is that mountainous areas are often refuge areas (eg Johanna Nichols), where part of a population that used to live lower down has been pushed up (by invaders, for example, or through persecution forcing a portion of the population to flee into the mountains), while another part that originally lived lower down is still there but has switched to the invaders' or persecutors' language. On the other hand, an ejective-rich language adopted by a population whose original language did not have ejectives (or had fewer of them) may lose them in the process, while remaining a member of a language family which has continued to exist and whose other members have kept the ejectives. The presence or absence of ejectives then would have as much to do with the history of the speech communities as with the altitude at which they settled.

Have such possibilities been taken into consideration as potential explanations for the (often, though not always) observed correlation?

Daniel Ezra Johnson said,

June 15, 2013 @ 3:12 am

1) when you give a press release, how can you claim surprise at media interest?

2) am i missing something with my point about the physics (above)? couldn't someone at low altitude produce a less compressed ejective with the same force and effort as the high-altitude ejective? and moreover a similar effect?

Dan Everett said,

June 15, 2013 @ 5:14 am

Daniel Ezra Johnson – Since I have some experience with surprise at media interest le me respond to one of your points. The author isn't the one in these cases to make the press release. This is done routinely be presses, journals, and university pr depts. The vast majority are ignored by the media. Hence the author's surprise when suddenly the media comes calling.

Daniel Ezra Johnson said,

June 15, 2013 @ 6:30 am

OK, fair point. Indeed, I've been pleasantly surprised to have research covered by a popular blog, without any forewarning. Although in this case, the author is interviewed (that is to say, there's a sound file of him explaining the basics of the paper) in the release by U. Miami. But that doesn't mean he knew it would be a sensation.

But I'm also interested in understanding why my suggestion about air pressure, altitude, and ease of ejecting is (apparently) wrong…

Kyle Gorman said,

June 15, 2013 @ 11:07 am

The proposed mechanisms may be "explicit and precise" (as Sean says), and in that this study is superior to many other typology-correlation studies. But I cannot help but seeing them as patently silly. What is the evolutionary story for the "water-vapor saving" hypothesis? Are we really to imagine speakers of languages with only pulmonic egressive consonants dying of dehydration where speakers of languages with mixed pulmonic/glottalic inventories thrive? Is there any other way this apparent bit of teleology in consonant inventory have arisen? Sexual selection perhaps ("don't date that guy, he's a dehydration case waiting to happen")?

Y said,

June 15, 2013 @ 10:48 pm

To add to Kyle Gorman's comment:

Suppose you spend half your waking hours in conversation. So 16/2 = 8 hours, of which you (hopefully) take half, i.e 240 minutes. Say 10% of this time is spent on stop bursts, i.e. 24 minutes a day of inefficient stops. For ejective languages, some fraction of these(say a half) will be ejectives. These are 12 minutes of "more efficient" bursts. Say you are saving half the water vapor by using ejectives. That's the same effect as not talking an extra 6 minutes a day (out of the 8 hours of conversation / 24 hours of breathing). Or you can just take an extra sip of water every day.

Daniel Ezra Johnson said,

June 16, 2013 @ 1:14 pm

Of course, with a whole series of ejective consonants, words are going to be much shorter. You can say the same amount and stop talking by lunchtime.

Ejectives, High Altitudes, and Grandiose Linguistic Hypotheses | GeoCurrents said,

June 17, 2013 @ 11:53 am

[…] and social realms can be, and have been, explored; as Mark Liberman notes in his LanguageLog post, “many relevant linguistic and non-linguistic datasets are now pre-compiled and available for […]

Sean Roberts said,

June 17, 2013 @ 3:29 pm

Following a suggestion from Chris Lucas, I've looked at how population size and langauge contact effect the results. I find that population size is actually a better predictor of ejectives.

Mike Maxwell said,

June 17, 2013 @ 11:07 pm

I'm just hoping we don't see an article on why climate change may result in further endangering languages with non-sonorous sounds.

marie-lucie said,

June 18, 2013 @ 6:42 am

Sean Roberts: I find that population size is actually a better predictor of ejectives.

So what do you take from that finding? that a shrinking population causes ejectives to appear (by what mechanism?)? or that a remnant population keeps its inherited ejectives, while a population that has merged with another (ejectiveless) population loses them?

marie-lucie said,

June 18, 2013 @ 7:19 am

I have actually run into one case of ejective "creation" or spontaneous emergence.

Some years ago I had an American colleague teaching French in the same (Canadian) department I was in. His French was excellent, his pronunciation almost perfect, except for one detail: he would say dép'artement, p'artir, p'arler, P'aris, and similarly for other lexical words containing the sequence par, or perhaps more generally pVr. I think that the effort he made in anticipation of a uvular r caused him to constrict his throat. I only noticed this feature with p, and did not try to study his speech systematically at the time. He may have done the same thing with other voiceless stops but the effect may not have been as conspicuous as with p.

Caleb said,

June 21, 2013 @ 1:37 am

Someone mentioned the replicated typo update to me, so I thought I'd come back here and make a couple of points. Overall, the reanalysis added strength to my claim by taking into account familial relationships. There are a couple of problematic assumptions in the latest post, though some interesting points worth pursuing. Interestingly, though, the most crucial data in my article were ignored in the reanalysis (despite my urging above). The clustering of languages with ejectives in high elevation zones is simply not in dispute. We can choose to assume that there is simply a coincidental association between non-pulmonic egressive sounds and high elevation areas (and some like Mark seem willing to do so), or we can attempt to test the physiologically based hypotheses I offered and others, even ones relating to indirect effects of geography on population size. I opt for the latter choice. With respect to the geocurrents blog, I find so many oversimplifications and mischaracterizations I'm not sure where to begin. I'm honestly a bit tired of discussing this topic (I've lost track of the number of interviews at this point), and blogs aren't IMO the place to settle this anyhow. My hope is that someone follows up on this with relevant peer-reviewed research. Until then…

Rudy Troike said,

June 24, 2013 @ 12:14 am

Most of the discussion has involved abstract statistics. But face validity is an essential (though often overlooked) starting point.

Two questions have not been answered: (1) how was distribution with respect to altitude determined? and (2) what controls were placed on genetic relatedness?

Quechua, given the Inca capital in Cuzco, can certainly be a poster child for this correlation. But (a) some Quechua speakers live in lowland areas, and there are comparative linguistic connections which suggest that Quechua speakers originally lived at a much lower altitude, and (b) it has been suggested that ejectives are not original in the language, but were borrowed from the originally higher-cultural language group, the Aymara.

And how was the exclusive association of altitude and ejectives determined? Korean certainly has a class of ejective consonants, but is hardly a high-altitude language.

Jim Scobbie said,

June 25, 2013 @ 7:14 am

Ejectives are certain to occur as phonetic variants of certain phonemes, paralinguistically, or as epiphenomena of various kinds in more languages than they occur phonemically in, yet in all these cases individual speakers are "making an effort" for production or perception reasons. Functional explanations are useful to explain the appearance of these sounds, like any others, and of non-phonemic use of sounds, as well as phonemic ones, and the issue of phonologisation itself.

A social contract is needed, a community of speakers with a consistency in the use of these sounds, and probably a set of contrasts with other sounds, in order for us to view them as / for them to be phonemic. So a phonemic /k'/ is well evidenced in a language where many speakers approximate it to IPA [k'] and it is in opposition to, say, plain /k/ and /g/. Ejectives can be approached as a family of speech sounds, not something as simple as a canonical IPA target [k'], especially a [k'] produced by a linguist in a lab. Speakers will vary in the coarticulation, timing, and intensity of ejectives in different positions, contexts and languages. As is known, "ejectives" are not all the same, even within a language.

Social factors interacting with cognitive, physiological and others make for a very complex mix, in which sometimes some factor is so powerful that there is a simple explanation for some linguistic pattern, but not often. We seem to have very little detailed or complex data to base realistic models on, is the feeling I have. The combination of factors needed to create and/or preserve ejective systems in the face of linguistic change and social movements of peoples and languages isn't something I can really comment on at all, other than to surmise it will be complex.

However, I have one comment to make, which is that it's clear that people use ejectives, and it may be that social groups adopt them, at low altitudes, at least in some word positions, in languages not reported in these databases. Not phonemically, I agree, but sub-phonemic use of ejectives might be just as important as phonemic ones for understanding functional pressures (no pun intended).

Marie-Lucie mentions an individual above, and that's what's prompting me to add something to the discussion… because in an edition of JIPA coming up, you will find papers that discuss the use and distribution of ejectives in more detail – for example in Scottish English and German. They have been noted in the past but this special issue brings together a number of papers on the topic (and other non-pulmonics in places you might not expect them), with nice references and contemporary work.

I'll just mention Scottish English here, a language in which you can anecdotally observe ejectives of /ptk/ in particular quite readily.

a. Gordeeva and Scobbie's JIPA paper analyses ejectives in an adult experiment in detail, but summarises a previous child study (semi-spontaneous play). In that group of children, 5 out of 7 used ejectives, and for those,13.5 % of all word-final obstruents involved glottalic stops. Prosodically, these ejectives appeared significantly more frequently in phrase-final positions. In terms of phonological contrast, they appeared mostly in lexemes ending with phonologically voiceless stops, but 12% of these ejectives were in items "pig" and "food" accompanied by complete de-voicing.

b. McCarthy and Stuart-Smith's JIPA paper discusses girls from Glasgow, looking at read and spontaneous speech. They look at interplaying phonetic, linguistic, interactional and social factors conditioning their appearance. A draft of the paper (stuart-smith p.c.) says "Overall, we find that using ejectives for word-final /k/ is very common for these Glaswegian girls" read speech shows 4/5 are ejectives, a bit more than in casual speech.

Both papers look at the nature and distribution of ejectives in more detail, but you can see the headline rates. Other papers by Ogden, Fuchs, and Simpson – either in that special issue or cited there – make further interesting contributions to the discussion about where the systematic use of ejectives can be found around the world. There is already a literature on different kinds of ejectives – i.e. how 'strong' they are, which also seems very relevant to the point at hand.

Correlation and causality | swphonetics said,

August 16, 2013 @ 6:20 pm

[…] Sounds: The Case of Ejectives, PLOS ONE, 2013 (accessed August 2013), reviewed and discussed on Language Log on 14 June […]

Correlation and causality: ejectives | swphonetics said,

August 29, 2013 @ 5:35 pm

[…] Sounds: The Case of Ejectives, PLOS ONE, 2013 (accessed August 2013), reviewed and discussed on Language Log on 14 June […]

Big Data Will Blind You said,

October 8, 2013 @ 10:50 pm

[…] what’s really going on? What's causing the correlation? Well, as far as the ejectives go, Mark Liberman at language log points out that there are hundreds of linguistic features, and thousands of languages; and in a […]

Caleb said,

November 1, 2013 @ 8:25 pm

If anyone would like to read more on this topic, I have posted a paper on my web site (calebeverett.weebly.com) presenting more evidence for the correlation in 3700+ languages, and addressing some common misconceptions and objections regarding the correlation, including the main one raised by Mark. FYI, there is also more forthcoming work on the topic of geography and sound patterns (unrelated to ejectives).

Jim Scobbie said,

July 5, 2014 @ 4:53 am

Another paper on this topic – Ejectives in English and German : Linguistic, sociophonetic, interactional, epiphenomenal? – by Adrian Simpson – in which he also takes the approach that you don't look at phonemic inventories as a gold standard for the initial point from which you can hope to understand functional pressures on phonemic inventories… but instead looks at phonetic behaviour directly. That means looking at coarticulatory and subphonemic behaviour.

It's in Celata, Chiara and Silvia Calamai (eds.), Advances in Sociophonetics. 2014. vi, 214 pp. (pp. 189–204)

Abstract: This paper describes the phonetic form, the distribution and the possible functions of ejectives in English and German, proposing that ejectives are on the increase in different varieties in English. The problems of teasing apart the different contributions of allophonic regularity, interactional function, sociophonetic variability and epiphenomenal inevitability in accounting for ejectives in English are discussed. Possible production mechanisms behind ejectives in both languages are explored and doubt is cast on previous epiphenomenal accounts which have ignored the importance of a pulmonic component in creating the necessary intra-oral pressure increase. This, in turn, raises questions about possible production mechanisms behind ejectives in languages in which they play a regular part in the phonological inventory.

Jim Scobbie said,

July 5, 2014 @ 5:24 am

Here is the link to the special issue of JIPA (Dec 2013) edited by Adrian Simpson on non-pulmonic sounds in European Languages

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayIssue?decade=2010&jid=IPA&volumeId=43&issueId=03&iid=9062042 with some papers on clicks and ejectives and pre-aspirated consonants at sub-phonemic or, as Helgasson calls is, non-normative, levels of systemisation.

Everett's argument about inventories is that ejective variants of otherwise pulmonic voiceless stops become more likely to be phonemicised / phonologised as a main correlate/cue when the functional value as perceptual cue or via ease of production (or both at once) relative to some category/ contrast is enhanced. Part of that story would need to be that ejectives arise naturally for certain categories/contast-members in certain sorts of contexts, but don't tend to become embedded as the most obvious phonetic variants of a phonological category. Perhaps these papers on ejectives in English or German show some of the routes in which there is either random of motivated (aka functional) reasons why there are ejective variants in the production/perception multi-dimensional phonetic space in the first place.