Peeving and changes in relative frequency

« previous post | next post »

What follows is a guest post by Bob Ladd.

When I lived in Germany in the early 1980s, I bought a few style guides in the hope of improving my written German. One of them turned out to consist primarily of what I would now (as a long-time Language Log reader) recognize as ‘peeving’ – short essays about clichés, neologisms, and trendy new expressions that drove the author crazy. Among many other supposed novelties, the guy hated the expression ich gehe davon aus, which (as I had noticed myself) is used to mean ‘I assume’. Literally, ich gehe von X aus just means ‘I go from X out’, i.e. ‘I start from X’, but the grammar of German is such that X can be a clause. The ‘assume’ meaning comes from ‘I start from [the assumption that] CLAUSE’.

In my German mental lexicon I took note that this was a new-fangled expression that annoyed people, and thought no more about it until yesterday, when (for reasons that made sense yesterday) I was reading what Otto Jespersen said about stress in his 1912 Elementarbuch der Phonetik. To my surprise, Jespersen noted that the ‘weak stress’ mark can be omitted in transcription, because we assume – wir gehen davon aus – that a syllable unmarked for any level of stress is weak. This took me back to my German style guides to make sure that I was remembering this right, then I fired up Google. One of the first things I found was a piece in a language column (‘Redensarten’) in Die Zeit in 1983, complaining light-heartedly about ich gehe davon aus in terms very similar to my style guide’s. So clearly, in the early 1980s, this was an expression that people – or peevers, anyway – loved to hate. But it wasn’t new. From reading Jespersen I now knew that it had been around at least since the early 20th century, and a little further googling even got me back to a clear example from 1839.

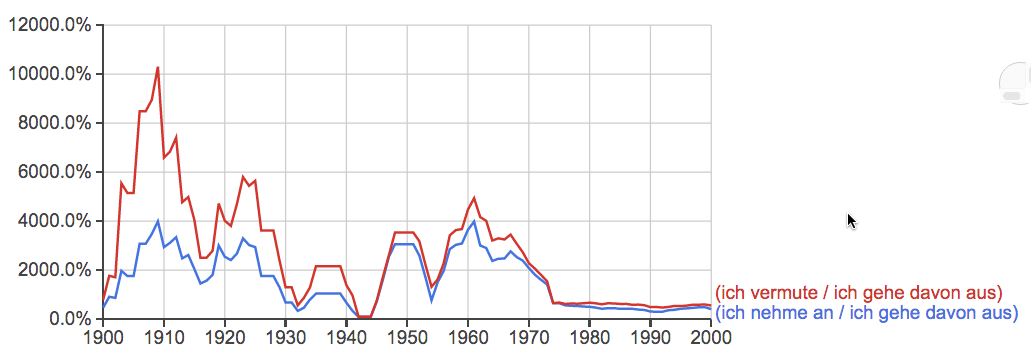

And yet: turning to Google n-grams, I found that there really was something new about the expression in the early 1980s. Until about 1965, the expressions ich nehme an (‘I assume’) and ich vermute (‘I suspect’) were both more than ten times as common as ich gehe davon aus. But then the graph for ich gehe davon aus suddenly heads skywards, so that by 1982, the middle of my time in Germany, the gap between it and its more established competitors had narrowed to a factor of only three. It must be this shift that drew the attention of the peevers.

Language Log has often talked about the ‘recency illusion’, where you think an expression is new but it’s been around for ages. In a sense, it’s fair to call this an illusion – but like a lot of real illusions, it may be based on misinterpreting something that we do perceive accurately: changes in relative frequency. The same thing probably applies to complaints about English hopefully as a modal adjunct or sentence adverb, which drove purists in the 1960s and 1970s to distraction and implausible etymologizing. An article by Stan Whitley in American Speech in 1983, written long before the existence of Google n-grams, made a good case that this was actually an old usage that somehow, abruptly, became much more common starting in the late 1950s. A Google n-gram (do a case-sensitive search for sentence-initial ‘Hopefully’, which is unlikely to be a manner adverb) seems to show that Whitley’s conjecture was correct.

Above is a guest post by Bob Ladd.

(myl) There have been several earlier LLOG posts about cases where peeving seems to have been spurred by changes in usage frequency, e.g. "In this day of slack style", 9/2/2012, and "Regardless whether Prudes will sneer", 12/10/2012. See also these reflections on prescriptivism in continental Europe — "Ask Language Log: Prescriptivism in Europe", 8/21/2009.

And Google Ngram viewer's picture of the relative frequencies of the cited phrases seems not quite as Bob describes it, though perhaps this is due to gaps in the publishing record during WWI, the early years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and WWII:

Andreas Johansson said,

March 24, 2018 @ 10:33 am

Did the book explain what was supposed to be wrong with the expression?

Swedish has a similar expression jag utgår från att … "I go out from that …" meaning "I assume that …". Funnily enough, it affixes the particle to the verb, whereas a physical leaving would be expressed with a separated particle : jag går ut från … "I go out from …".

Robert Coren said,

March 24, 2018 @ 10:35 am

Am I correct in assuming that when you say "such that X can be a clause" you mean that a common form of this usage is "Ich gehe davon aus, daß…"?

~flow said,

March 24, 2018 @ 11:45 am

This reminds me of the of TV show "Was bin ich" with popular host, Robert Lembke, and a jury of four personalities. The rules of the game were utterly simply, the atmosphere was cheerful, and all you could win was ten times five deutschmarks, which even at that time was not a lot. Which brings to me to the consistently and persistently repeated proceedings of that show. "Welches Schweinderl hättens denn gern?" was a household expression back then; back then, you could totally use it to stand in for "which one do you like?", and you'd be sure of the smiling faces and the jocular remarks. These rituals got so famous in the culture Wikipedia has a chapter on them as I just discovered: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Was_bin_ich%3F#Ritualisierte_Spr%C3%BCche. Now, Wikipedia does have "Gehe ich recht in der Annahme, dass Sie nicht…?" (am I right in assuming you do not…?"); it does not list "Kann ich davon ausgehen, dass…?". Yet in my memory the words conjure up this show, and maybe similar ones from the period like "Dalli-Dalli" all of which were invariably highly ritualized and used lots of set expressions of which many found their way into daily usage.

David Marjanović said,

March 24, 2018 @ 4:22 pm

Heh. The expression is indeed common. I never thought it was new or saw anyone complaining about it – but I've only read one style guide ever, and, as it happens, I was born in 1982! Die Gnade der späten Geburt ("the mercy of late birth").

Yes.

(Except that the spelling reform of 1998–2005 has restricted the ß to the positions following long vowels and diphthongs and has therefore turned daß into dass.)

Frans said,

March 24, 2018 @ 4:22 pm

@Andreas Johansson And in Dutch: "Ik ga ervan uit dat…" I go therefrom out that, same as in German. Or better phrased in English: I depart from [the assumption] that…

With a quick search I wasn't able to uncover any attestations from before 1894, so now I'm left wondering if this could secretly be a Germanism.

Frans said,

March 24, 2018 @ 4:31 pm

I just noticed I mistyped the year. I meant 1893. A distinction of no importance of course, but I suppose adding a link to the source might nevertheless be worthwhile as an addition.

Geoff said,

March 24, 2018 @ 5:22 pm

Ich gehe davon aus – mmm, sounds pretty good to me.

An advantage of being an L2 learner is that you can take the language as you find it without being bothered by the careful native speaker's lifetime of idiosyncratic peeves.

Bart said,

March 24, 2018 @ 7:54 pm

As a non-native speaker of German and Dutch I have an idea of a slight difference of strength between

(1) Ich gehe davon aus dass.. / Ik ga ervan uit dat..

and

(2) Ich nehme an dass .. / Ik neem aan dat ..

as a way of saying I assume that ..

The first seems stronger. Its what youd use to say that you assumed that your son was not guilty of some crime. The second is more appropriate for something trivial, eg assuming that there must be something worth watching on tv tonight, or else for something unemotional, eg stating assumptions before a mathematical proof.

If that is so, then there might once have been cause for peeving about people who use Ich gehe davon aus dass.. / Ik ga ervan uit dat.. for assumptions where the more restrained Ich nehme an dass .. / Ik neem aan dat .. is more appropriate.

Just a speculation from a non-native speaker.

Zeppelin said,

March 24, 2018 @ 8:05 pm

Interesting! I hadn't encountered that particular peeve before, but then I've never read a style guide either. The peeves I hear about most these days (as well as my personal ones) tend to be syntactic anglicisms.

Lars said,

March 24, 2018 @ 10:33 pm

As Andreas says, there are equivalent expressions in the Scandinavian languages. As a Dane, I've never considered it new, or that there could have been a recent uptick in its use.

It's in Ordbog over det Danske Sprog (which covers the years 1700-1950). The source is a dictionary dated 1859 if I'm reading the references right; there's a different one (a natural history text) a century older, but the usage there is somewhat different.

phspaelti said,

March 25, 2018 @ 3:01 am

@Frans: Or better phrased in English: I depart from [the assumption] that…

While I understand what you are trying to say here, you should be aware that while "depart" historically might mean "start from", the translation comes to pretty much the opposite.

German "ich gehe davon aus dass X" would mean that you basically accept X as true (though perhaps adding qualifications later), while English "I depart from X …" would usually be taken that you reject X.

Frans said,

March 25, 2018 @ 3:38 am

@phspaelti Of course. In English you'd simply assume, or start/begin/proceed with the assumption.

(Although I'm not sure if departing from an assumption means quite the same thing as departing from, say, your values.)

By better phrased I meant as a grammatical English sentence, to better illustrate what it is we actually say without the distraction of awkward artificial constructions.

Bob Ladd said,

March 25, 2018 @ 7:25 am

Mark suggests that there seems to be something weird with the data, but I think this is mostly an artefact of the extremely compressed y-axis in his graph, which is caused by the fact that in the first half of the 20th century ich gehe davon aus was fairly rare. If instead we plot the reverse ratios (with ich gehe davon aus in the numerator rather than denominator), we see the pattern I discussed. There’s also an issue about case-sensitivity in the Google data, because ich gehe davon aus is very frequent in sentence-initial position. To avoid clogging up the comments with this kind of stuff, I’ve put a ridiculously detailed discussion here for anyone who’s interested.

@ Andreas Johansson and others: The 1980s objections to ich gehe davon aus revolved around the idea that the expression seemed to distance the speaker from responsibility for the proposition being assumed, which (among other things) supposedly made it ideal for evasive public utterances.The style guide I bought in the 1980s (Rudolf Walter Leonhardt, “Auf gut deutsch gesagt: Ein Sprachbrevier für Fortgeschrittene”) said “Nobody assumes or presupposes or is sure that something is happening, they all just start from there.” (“Kein Redner der achtziger Jahre nimmt an, setzt voraus, ist sicher, dass etwas geschieht. Sie gehen alle immerzu davon aus.”) The article in Die Zeit that I mentioned in the post makes a similar point.

It’s interesting that the same expression exists in all the other Germanic languages except English. I suppose this is conditioned by the existence of the relevant comparable lexical and syntactic structures, which are absent in English.

Bob Ladd said,

March 25, 2018 @ 7:33 am

Sorry, here are the links in correct form. They got mangled between one platform and another, but there's no way to test them without submitting the comment, so you'll have to copy and paste.

My followup: http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/~bob/LgLogFollowup.pdf

The Zeit article: http://http://www.zeit.de/1984/01/ich-gehe-davon-aus-dass

Andrew (not the same one) said,

March 25, 2018 @ 8:58 am

I have seen people – probably not first language English speakers – writing things like 'Smith departs from the assumption that…' (meaning that he does assume that, not that he abandons the assumption), and although it's generally possible to work out from context what they mean, it's terribly confusing.

('I think 'sets out from the assumption…' would convey the same point while generating less confusion.)

Robert Coren said,

March 25, 2018 @ 9:35 am

@David Marjanović: So now I'm trying to decide whether I'll be a stubborn old man and continue to use ß in the old way, or just eschew it altogether, since there's no way at this point that I'm going to remember where it's still considered correct.

Topher Cooper said,

March 25, 2018 @ 11:35 am

"And Google Ngram viewer's picture of the relative frequencies of the cited phrases seems not quite as Bob describes it, though perhaps this is due to gaps in the publishing record during WWI, the early years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and WWII"

Any such effect would, presumably, be due to chance fluctuations resulting from higher variance, rather than a direct effect of lower publishing rates. The scores on the dependent axis of Google Ngram viewer plots have been normalized for publication volume within the year:

"Many more books are published in modern years. Doesn't this skew the results?

It would if we didn't normalize by the number of books published in each year."

from the FAQs section of .

Topher Cooper said,

March 25, 2018 @ 11:37 am

Sorry, spaced out: the citation was for slash slash books dot google dot com slash ngrams slash info.

David Marjanović said,

March 25, 2018 @ 3:07 pm

I think I agree. :-) Of course there's a broad overlap zone that leaves peevers plenty of room to have preferences.

I rather suspect it's calqued from 19th-century German academic writing. Many scientific terms, including "science" itself (Wissenschaft, Swedish vetenskap, even Dutch wetenschap…), show the same distribution.

Many native speakers have made the same decision, one way or another. :-) But, actually, it's simple. The old rule was based on writing: use ss if you can separate syllables through it, ß otherwise.* The new rule is based on the language itself: use ss behind short vowels, ß behind long ones and diphthongs. Thus, Einfluß, beeinflussen, beeinflußt ("influence, to influence, influenced") has become Fluss, beeinflussen, beeinflusst.

* Bizarrely, it wasn't taught that way. It was taught as a set of several much less intuitive rules. No wonder so few people consistently got it right.

Oliver Urs Lenz said,

March 26, 2018 @ 11:07 am

@Bart: As a native speaker of both, I agree that aannemen/annehmen seems less felicitous in the son-murder situation, and a stronger historical distinction between the two could well have motivated the peeving.

But I wonder what the dimension is along which they differ. My impression is that aannemen/annehmen is perhaps more formal, as supported by the fact that aannemen is used in formal (mathematical) reasoning and that aanname is the natural translation of hypothesis.

I also feel that in common speech, I would only use aannemen/annehmen in rethorical questions, whereas I easily use ervan uitgaan/davon ausgehen in declarative statements.

Oliver Urs Lenz said,

March 26, 2018 @ 11:20 am

Sorry, where I said 'rhetorical questions', I actually meant declarative statements used as questions, like "Ik neem aan dat …?". I now realise I do also use these simply as statements,, to convey my impression of some state of affairs ("I guess that…"). In contrast I would rather use ervan uitgaan to describe a working hypothesis that conditions my behaviour ("I am working under the assumption that…").

Andrew Usher said,

March 26, 2018 @ 9:38 pm

David Marjanovic:

I don't know if you've been told too may times before, but in English 'behind' is not used that way. It's always 'after' – a word that is common Germanic but has been lost in High German. Originally it had the temporal meaning it still retains, but has been extended to replace 'behind' in the meaning 'later in a sequence'. The opposite of 'after' is normally 'before'; of 'behind', 'in front of'.

So it is: "use ss after short vowels, ß after long ones and diphthongs." This is not just a matter of taste; it's a distinction English makes and German doesn't.

As for 'depart from the assumption that', it's quite rare and doesn't seem analogous to the other Germanic languages. Further, as you can already see, English requires adding the word 'assumption' anyway in order to attach a full clause. We can't say 'depart from [CLAUSE]' which would be truly analogous.

k_over_hbarc at yahoo.com

Frans said,

March 27, 2018 @ 3:16 am

@Andrew Usher

I disagree with your last argument. Strictly speaking er is the unstressed form of daar (there), hence why I wrote "therefrom" previously. But for what it's worth, in a context like ervan it would often be more accurate to say that it means it or them.

In Dutch syntax:

"We start itfrom that…"

"We start therefrom that…"

In more English-like syntax:

"We start from it that…"

"We start from there that…"

It or there doesn't make much of a difference to the principle. What's it? Where's there? Hence I would regard these two sentences are functionally (near-)equivalent:

We gaan [er]van uit dat

We gaan uit [van de aanname] dat

The latter is certainly formal and perhaps even stilted, but you'll find it plenty in the likes of EU and medical documents.

Sarah said,

March 27, 2018 @ 1:50 pm

@Andrew Usher re: "behind" vs. "after"

Could this be an American vs. British (or other variety of English) thing? As a American English speaker, David Marjanović's use of "behind" seemed fine to me. If I had written the sentence myself I probably would have used "after", but "behind" caused me no confusion. (I think I understand the distinction you are making, but I don't think it's relevant to David's usage. "Behind" is also used spatially, e.g. "the wall behind the cabinet". If you think of a word spatially, as written on a page, then the beginning of the word is the front and the end of the word is the back, and ß is then behind the vowel.)

Samantha said,

March 28, 2018 @ 4:12 am

Interesting post! I learned "annehmen" from a dictionary and used it in my school German, but immediately dropped it in favor of "ich gehe davon aus" once I went to Germany and heard it constantly. I had no idea it was once the subject of peeving.

Andrew Usher said,

March 28, 2018 @ 5:34 pm

Sarah:

David's use of 'behind' didn't confuse me either, but instantly struck me as not English and the mistake of a foreigner that had not mastered on particular distinction in English (as mentioned, German doesn't have it). If you think and native English-speaker (esp. American) would use 'behind' like that (with no additional spatial analogy possible), you might provide a real example.

'The wall behind the cabinet' is of course normal, and illustrates my point that 'behind' and 'after' are nearly always mutually exclusive in English, as you couldn't say *'after the cabinet'.

Frans:

I can't be sure what you mean, and I wouldn't dare challenge any of your statements on Dutch, but the English equivalents you give are absolutely impossible. English really doesn't have an equivalent to 'ich gehe davon aus'.

Frans said,

March 29, 2018 @ 2:38 am

@Andrew Usher

You wrote this:

"Further, as you can already see, English requires adding the word 'assumption' anyway in order to attach a full clause. We can't say 'depart from [CLAUSE]' which would be truly analogous."

But we don't say "start from [CLAUSE]." We say "start from it [= de aanname/the assumption] that…" The phrase "we start from that apples are green" would be ungrammatical. In English such hidden antecedents occur plenty as well, albeit presumably not in contexts fully analogous to this example, but it's frowned upon in formal writing. And so it is in Dutch, except in a few idiomatic constructions like this one. You can easily imagine people peeving about it too, with the argument that you don't really know what "it" means even though everyone knows it refers to the concept of an assumption.

David Marjanović said,

March 29, 2018 @ 6:51 pm

Hm. German does offer a choice of nach vs. hinter, which seems to correspond to after vs. behind pretty well; you could absolutely use nach in my examples in German, and now that I think about it it would probably even be the more usual choice. Maybe I've read too many phonology papers that talk in all seriousness about "the right edge of a word" to mean its end, confusing language with the Latin alphabet (or IPA) in the most jarring manner.