Nontrivial script fail

« previous post | next post »

We have recently encountered an "Epic Dictionary Fail". Today, I should like to consider what happens when a script fails.

The following signs are affixed to a dentist's office in Taiwan. The one in vertical orientation reads

Shìmín yáyī 世旻牙醫 (Shimin Dentist):

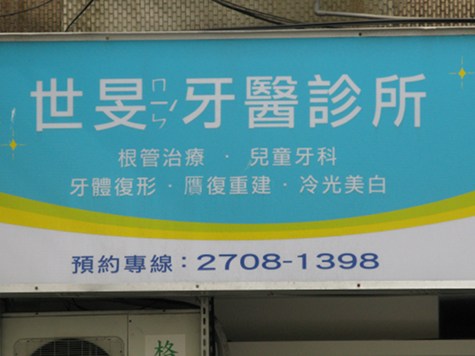

The sign in horizontal orientation reads

Shìmín yáyī zhěnsuǒ 世旻牙醫診所 (Shimin Dental Clinic)

(Underneath are listed the services provided by the clinic)

The person in charge of the clinic is Lǐ Pèiyǐng 李佩穎, and the office is located at Dà'ān District, Fùxīng South Road, Section 2, Alley 151, No. 7 in Taibei 台北市大安區復興南路二段151巷7號.

What attracted me to the signs on this clinic are the little marks next to the character mín 旻 ("sky; autumn"). These are informally called "bopomofo" after the first four sounds of this phonetic system (a semisyllabary plus tonal diacritics), which is somewhat more formally referred to as Zhùyīn fúhào 注音符號 (Phonetic Symbols). More complete and exact designations for the system in Chinese and English are given here.

While such symbols are by no means ubiquitous in Taiwan, one encounters them often enough that they begin to have an impact. One wonders why the Chinese writing system so often needs a separate script for phonetic annotation.

The reason seems to be that readers often have little or no idea how to pronounce particular characters. The owner of this business, for whatever reason, wants to use the character 旻 in the name of their clinic. At the same time, they are keenly aware that many, if not most, potential patients do not know how to pronounce the character 旻 (and probably don't know the meaning either). Hence, they have resorted to Zhùyīn fúhào (bopomofo) to make the pronunciation clear.

I find this situation to be extremely thought-provoking. After all, Chinese characters are supposed to be able to represent speech, so it seems odd that users need to resort to a separate writing system (bopomofo) to clarify how a word should be pronounced. I refer to this as the "furiganaization" of the Chinese script, and have written about it in "Pinyin as Furigana" (3/23/2011) and elsewhere. Furigana are the ruby symbols used in Japanese for the phonetic annotation of texts for learners, and also often for low frequency words, proper names, and unusual pronunciations of kanji (Chinese characters).

As a learner of Chinese in Taiwan four decades ago, I was deeply grateful for the existence of extensive reading materials at all levels that were phonetically annotated with bopomofo. That saved me endless hours of dictionary drudgery and frustration. There was (and still is) an excellent newspaper called Guóyǔ rìbào 國語日報 (Mandarin Daily) that had (and still has) all of its articles phonetically annotated with bopomofo. There are also the wonderful series of literary supplements (periodically collected into books) entitled Gǔjīn wénxuǎn 古今文選 (Anthology of Ancient and Modern Texts) and Shū hàn rén 書和人 (Books and People). Moreover, bookstores in Taiwan are stocked with hundreds of premodern texts, both classical and literary, that are not only annotated with bopomofo, but accompanied by translations into Mandarin and extensive commentaries and notes to assist the reader. My favorite series of this sort is published by Sānmín shūjú 三民書局 (with aquamarine covers and white lettering). Táiwān yìn shūguǎn 臺灣印書館 (the Jīn zhù jīn yì 今註今譯 [modern notes and translations] series, with dark blue pseudo-threadbound covers and white lettering) has excellent commentaries and translations, but unfortunately no phonetic annotations. These two series are of very high quality and are prepared by the top scholars in Taiwan. There are many other similar series in Taiwan, not a few with complete phonetic annotations, which shows how seriously people there take reading and understanding classical and literary texts. Presently, I do not know of anything comparable in the whole of China. There are some Mandarin translations of classical and literary texts on the mainland, but none that have phonetic annotations throughout.

Time and again, I have urged the educational and cultural authorities in China to use Pinyin for the same purposes, although they have been very reluctant to do so, partially because of technical difficulties of setting the ruby symbols in an orthographically correct and esthetically pleasing manner. Now that these technical problems are being solved by computer programmers and software experts, I expect that we will see more and more instances of Pinyin being used as phonetic annotation in the PRC. This is particularly the case because character amnesia is definitely on the rise.

In the thirty-five or so years that I have been teaching Mandarin and Literary Sinitic (Classical Chinese) to hundreds of native and non-native speakers, I have encountered (among others) the following categories of failure on the part of students to read and write the characters:

READING

a. has nary a clue as to the meaning and pronunciation of the character — draws a complete blank

b. has only a vague idea about the meaning and / or pronunciation of the character

c. can guess the rough, probable meaning of the character from context, but cannot pronounce it at all or can only make a stab at the pronunciation (often missing completely)

WRITING

a. knows more or less well the pronunciation and meaning of the character he / she wishes to write, but cannot put down even the first stroke for it

b. knows more or less well the pronunciation and meaning of the character he / she wishes to write, but can only sketch out parts of it without being able to complete the whole character is such a fashion that it would be recognized by others

c. knows more or less well the pronunciation and meaning of the character he / she wishes to write, and can almost write the entire character, but makes one or more errors, some of which are capable of causing the character to be misread or not / barely recognized by others

All of these types of errors are of a very different nature from those that are encountered in languages that use alphabets as their writing systems, since the reader of a text written with an alphabet can — with rare exceptions like the infamous made-up word "ghoti" — more or less accurately sound out the words with which they are confronted, and the writer who uses an alphabet to write a text can always approximate the sounds of the words he / she has in mind. Even though he or she may misspell some of the words more or less badly, the reader can usually make out what he / she intended.

The good news is that the phonetic annotation of Chinese texts, dictionaries, and online or software resources, whether relying on pinyin or bopomofo, can help substantially to alleviate all of these types of errors. Consequently, as someone who is committed to making Chinese languages better known throughout the world, I am a strong advocate of the widespread utilization of phonetic annotation of Chinese characters.

Those of you who are not interested in dry statistics can stop here. What follows (below the double rule) is merely my attempt to determine the frequency of mín 旻 among all characters in the Chinese writing system. I shall close this section by noting merely that structurally mín 旻 is actually a relatively simple character, with only 8 strokes in total. The average number of strokes for the top 10,000 characters is around 12. The frequency-weighted average number of strokes:

* For the most frequently used 2,965 characters: 9.10;

* For the most frequently used 1,253 characters: 8.91;

* For the most frequently used 733 characters: 8.65.

These statistics are drawn from Chih-Hao Tsai's [sic] "Frequency and Stroke Counts of Chinese Characters."

Mín 旻 consists of two simple components, rì 日 ("sun; day") and wén 文 ("pattern; character; script; writing; culture"), either one of which might serve as a semantic classifier ("radical") in various characters, but in mín 旻 it is rì 日 that is the semantic classifier and wén 文 that is the phonophore (N.B.: Cantonese man4 man6; Taiwanese bun [in a disyllabic word] or buun [by itself]).

Judging from the simple construction and medium frequency of mín 旻 among the top 20,000 or so characters, it is apparent that even literate Chinese do not know the pronunciation (much less the meaning) of the overwhelming majority of Chinese characters, which generally have more strokes and more components than mín 旻, and are much less frequent than mín 旻 as well. Indeed, I have had highly educated Chinese friends and colleagues tell me that they are uncertain of the pronunciation, meaning, and how to write many characters in Xīnhuá zìdiǎn 新華字典 (Xinhua Character Dictionary), the standard single character dictionary (see next paragraph below) for the PRC, which has sold well over 300,000,000 copies. In short, simple and innocent though it may appear, mín 旻 — together with the three phonetic symbols (ㄇ ㄧ ㄣ) and the 2nd tone diacritical ´ next to the ㄧalongside it — speaks volumes about the nature of the Chinese writing system and the challenges it poses for its users.

Mín 旻 does not occur among 9,933 characters on this list, but it does occur in the Xīnhuá zìdiǎn 新華字典 (Xinhua Character Dictionary), my favorite portable character dictionary (zìdiǎn 字典), which has a little over 10,000 characters.

Mín 旻 occurs about 1/4 of the way down on this list of 13,060 characters, and is cited as occurring 860 times in a data base of 171,882,493 total characters, which is about 5 per million characters.

In the Linguistic Data Consortium's Chinese news corpus, it occurs 1,088 times in 605 documents, in a collection containing 1,368,064,442 characters in 3,087,084 documents, for a frequency of about 0.8 per million characters (where punctuation and some formatting characters are included in the total).

Finally, the Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì 汉语水平考试 (HSK / Chinese Proficiency Test) Vocabulary Guideline, 5th printing Beijing, 2008), which contains 8,000 characters, has completely dropped mín 旻. The HSK is based on the Xīnhuá zìdiǎn (see above) and is a very important standard for character usage, especially for learners of Hànyǔ pǔtōnghuà 汉语普通话 (Modern Standard Mandarin), but it has phased out 2,000 characters that are considered unnecessary to learn.

In the data bases that I have consulted, some of the discrepancies may have to do with different ways of counting characters (e.g., does punctuation get counted or not?), and some are no doubt due to genre or subject matter. Mín 旻 is far more likely to occur in "bookish" corpora than in general or news corpora.

Some words in English that are roughly comparable in terms of frequency, with their frequencies (per million words) in different sections of COCA, are:

| Spoken | Fiction | Academic | |

| fudge | 1.17 | 3.27 | 0.28 |

| snail | 0.37 | 2.93 | 1.82 |

| lobe | 0.62 | 2.58 | 3.29 |

| apex | 0.39 | 1.47 | 3.88 |

| scarlet | 0.98 | 11.95 | 1.69 |

Conclusion: Among the top 8,000-10,000 characters (which cover the vast majority of instances in most contemporary texts), mín 旻 is of low frequency. Among the top 20,000 or so characters (which cover nearly all instances in most modern texts), mín 旻 is of medium frequency. Among the top 60,000-80,000 characters (which cover virtually all [but not quite all] instances in the totality of premodern and modern texts), mín 旻 is of moderately high frequency.

[Thanks are due to Peter Leimbigler and Mark Liberman for statistical data, to Melvin Lee and Sophie Wei for Taiwanese pronunciation, and to Neil Kubler for sending me the photographs]

kktkkr said,

May 18, 2011 @ 8:18 am

I know a friend with this character in his name. Perhaps the frequent occurrence of characters in names may make up for their relative infrequency in running text (are names included in those corpora counts?) in helping people to pronounce them.

cameron said,

May 18, 2011 @ 8:19 am

If you took a Mandarin text fully annotated with bopomofo, and removed the actual characters, would a native speaker be able to read and understand the text? That is, can the bopomofo stand alone as a writing system?

T said,

May 18, 2011 @ 8:57 am

@cameron: depends on the text. I've seen lots of first grade children's books entirely written in bopomofo and as long as you use it for transcribing modern vernacular speech and you have some context, it's pretty accurate in capturing the sounds. But if you want to get formal … good luck!

Trimegistus said,

May 18, 2011 @ 9:30 am

Okay, this is a potentially offensive question, but if the Chinese themselves can't even read their writing system, why not quietly abandon it and switch to a phonetic alphabet already in use?

language hat said,

May 18, 2011 @ 10:12 am

Heh. You've just poked the hornet's nest, my friend; duck and cover! (I myself agree with you, but you're about to get all the contrary arguments expressed with great vehemence, if past experience is anything to go by.)

John said,

May 18, 2011 @ 10:28 am

@cameron: If it's a classical Chinese text, no. If it's a reasonably contemporary text, yes but with great effort (it will be a little bit like rendering an English text in IPA–people who have learned IPA will be able to understand every word, but reading it will be completely unlike reading a text in the standardized script.)

Could we avoid ridiculously hyperbolic assertions that Chinese people "can't read their writing system" based on the fact that people can't pronounce a character that only ever occurs in names nowadays? Do people say that English users can't write their own language because so many people can't spell definitely?

Dan T. said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:12 am

I remember a few occasions where, even in the Latin/English alphabet, somebody using a word or name judged likely to be unfamiliar to the reader added parenthetical pronunciation notes. An album from singer Sade adds (Shar-day), while some fast-food chain that once experimented with adding gyros to the menu noted beneath it to "say Year-O".

vanya said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:13 am

"why not quietly abandon it and switch to a phonetic alphabet already in use"

Because it just doesn't matter that much. Most Chinese can read what they feel like reading, and especially in a world of electronic media the inability to decipher an obscure character in a specialized, pretentious or archaic text just doesn't bother most people most of the time. The purely pragmatic argument against abolishing characters is that China and Taiwan (and Japan and even South Korea) seem to be doing a lot better at educating their populaces and creating economic value than most countries that use only phonetic scripts, so what's the problem? Characters do create a real "barrier to entry" for foreigners who want to learn Chinese, but to many Chinese (and to foreigners who have invested significant time in learning characters), that's a feature, not a bug.

Brendan said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:18 am

Interesting — 旻 is not exactly a common character on the mainland, but I can think of about four or five acquaintances who have it in their names, so I'd assume most people would know how to pronounce it.

The Zhuyin ruby brings to mind the immortal George Sansom quote, which unfortunately I don't have in front of me — something along the lines of, "as an avenue of study it may interest some, but as a practical instrument it is surely without inferiors."

Vladimir Menkov said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:20 am

Sure, I've seen pronunciation of rare characters annotated with Pinyin (and/or by reference to a common character with the same pronunciation). This is especially common in history books (e.g.., when they name the Six Dynasties emperors) or in museums (when they have items from such an era on display). However, I don't think that this phenomenon (having to explain pronunciation of words that are written in an unusual way) is any more common in Chinese than in a language like English, where foreign words are usually reproduced using the foreign language's (Latin) orthography, instead of being respelled. Thus, you often have parenthesized explanations like this: pianist Haochen Zhang (pronounced "Howshen Jhang").

Of course, educated Americans are sort of supposed to know that e.g. "ch" in the name of the German composer J.S. Bach is supposed to be pronounced differently from that in the more Americanized name of New York mayor Edward Koch…. but then, some Kochs would have it differently. Similarly, country names like "Iran", "Iraq", and at some point at time even "Italy" would have alternative pronunciations in some varieties of English.

This is less of an issue in languages such as Albanian, Azeri, or (Latinized) Serbian, where foreign words are typically respelled using the host language's spelling conventions, so you have "Medlin Olbrajt" or "Hillari Klinton"… but you don't see anyone promoting such a transcription system in English.

Victor Mair said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:06 pm

@John

definitly, definiteley, defanately, deaffunately….

I covered this in my post.

John Cowan said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:07 pm

The romanization problem is not so much with classical texts, which will need to be translated anyway to make sense to modern readers. It's that modern texts often have bits of classical Chinese embedded in them, and you can't just pinyinize the bits, as they will be unintelligible. What you need is a (necessarily imperfect) romanization system for Classical Chinese that allows the reasonably well-educated reader to reconstruct what was written. Needless to say, this is not as easy as reading bopomofo or pinyin off the page and consulting your native-speaker knowledge of what it means, but it's going to be much easier than learning zillions of hanzi.

Bob Violence said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:12 pm

I know Y.R. Chao came up with a romanization that supposedly worked with Classical Chinese ("General Chinese"), but I've never been able to find a detailed treatment of the system online. Does one even exist?

J. W. Brewer said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:48 pm

To expand on Vladimir Menkov's point, even domestic proper names are an area where spelling often fails to reliably cue pronunciation for native AmE speakers and/or different instances of what appears to be the same name will have different pronunciations. The difference between Houston, Tex. and Houston St., N.Y. simply needs to be learned. Proper names that came from non-English sources but have been subjected in different uses to differing degrees of Anglicization in pronunciation without being respelled are another source of such confusion/ambiguity.

That said, in the U.S., unusual surnames which fail to cue pronunciation sometimes get changed or respelled over time so that they will be more user-friendly. Is there an absolute taboo in Taiwanese society against respelling a family name or place name to substitute in a more widely-known / higher-frequency character with the same pronunciation and/or meaning?

That said, I quite like bopomofo (perhaps because of my youthful exposure to kana in Japan, although for all I know the Japanese parallel is actually a negative in China for political/historical reasons), and would be happy if Prof. Mair could convince the Communist regime on the mainland to scrap the ungainly Hanyu Pinyin in favor of an elegant phonetic-script solution that was actually custom-designed to fit the phonology of Mandarin.

xyzzyva said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:48 pm

Bob,

As always, I would start with Wikipedia.

xyzzyva said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:52 pm

J. W. Brewer,

If I were custom-designing a phonetic script for Mandarin, I would look to Korean hangul for inspiration, not Japanese kana.

Greg said,

May 18, 2011 @ 12:55 pm

why not quietly abandon it and switch to a phonetic alphabet already in use?

Actually we can see what happens when a language abandons Chinese characters in favor of a phonetic script. This is the difference between Korean and Japanese. North Korea abandoned the Chinese characters early on and South Korea has abandoned them gradually over the decades. What you find is, Koreans who've grown up learning just the phonetic script may not have a good understanding of Chinese-based words. This leads to eggcorns, which is to say holes in their understanding of the true meanings of words, because they don't know the Chinese characters that constitute a given, now purely phonetic, Korean word. The Japanese don't have this problem.

IMO the Japanese have a better understanding than Koreans do of the etymologies of the (very large) Chinese-based vocabulary in their respective languages. This despite the fact that Korean, compared to Japanese, has a richer phonology that better approximates Chinese pronunciations, and makes more frequent use of Sino-Korean pronunciations as opposed to native-language calques.

(I'm less sure that there's much benefit in Japanese to using Kanji to represent all native Japanese words, and indeed there has been a gradual trend toward the phoneticization of such words over the decades, for whatever reason.)

As a thought experiment, imagine if in English we switched to a purely phonetic alphabet. As an adult it would be extremely difficult to read (just as it is difficult to read a page of Japanese written only in Hiragana). I don't think it's an exaggeration to say it'd be like learning to read all over again.

This means that for the people who already know how to read (the adults), there is a large switching cost involved in moving to a purely phonetic system. Meanwhile, the switch really only benefits young learners, but those young learners aren't the "deciders".

Aside from that, with Chinese you have this rich history in the characters spanning millennia — does a country want to throw all that away because a seven-year-old doesn't want to study his reader?

I actually like the mainland China approach of simplifying the characters. This makes them easier to learn, but does not throw away the entire system.

blahedo said,

May 18, 2011 @ 1:44 pm

@J. W. Brewer "even domestic proper names are an area where spelling often fails to reliably cue pronunciation for native AmE speakers and/or different instances of what appears to be the same name will have different pronunciations.":

The big difference is that when that happens, we aren't totally stuck. We can "sound it out", we can write down or read out something that we can be confident is likely to be a reasonable approximation of the correct answer, if perhaps not exactly right. There are some exceptions, of course, and sometimes people will freeze up even if they know they could make a good guess because of the social consequences of getting an answer that was at all wrong. But the fact that these are even problems is a step up from the situation with Hanzi.

Rivers4 said,

May 18, 2011 @ 1:55 pm

Yet another rant from a foreigner who wants China to abandon its writing system because he finds it too difficult. Gosh, how will China ever become the world's second largest economy with such a cumbersome an inefficient writing system?

Oh, wait…

michael farris said,

May 18, 2011 @ 1:55 pm

Greg: "Actually we can see what happens when a language abandons Chinese characters in favor of a phonetic script."

Well nothing very drastic happened to Vietnamese… (besides a rapid increase in literacy). But alphabetic Vietnamese flourishes as a written language across a broader spectrum of the public than Chinese character Vietnamese ever did (AFAICT).

It's maybe not the best example because quốc ngữ in it's present form isn't a transciption of a particular dialect but a compromise orthography desgined to be accessible by most native speakers to a similar degree more like Italian or German orthography.

Some people complain that modern literate Vietnamese speakers lack a deep understanding of the etymology of the very large Chinese component in their vocabulary and this might well be true but it doesn't seem to stop them from reading or writing.

J. W. Brewer said,

May 18, 2011 @ 2:22 pm

My primary point was that dealing with unusual proper names is a sufficiently tangential issue that one can imagine ways to tweak the system to deal with it without abandoning the system as a whole, so that this is not a particularly good example for Prof. Mair's overall scrap-hanzi-for-pinyin agenda. The wacky/variable results that occur when rendering foreign names into hanzi, for example (subject of a prior post about "Iowa"), could be avoided by transcribing them into bopomofo the way the Japanese use katakana rather than kanji for that purpose. Just visually, the bopomofo characters look more kana-like than hanjul-like to me, but I don't know the history in terms of which (if either) of those systems was an inspiration. I have previously wondered whether the survival of bopomofo on Taiwan was enhanced by the population's pre-existing familarity with kana from the Japanese colonial period, as opposed to being a randomly politicized issue where the PRC did the opposite of whatever the ROC was doing (and/or vice versa) just to be contrary. But I don't know the answer.

Victor Mair said,

May 18, 2011 @ 2:57 pm

As Language Hat predicted.

@Rivers4

"Yet another rant from a foreigner who wants China to abandon its writing system because he finds it too difficult."

Who's the foreigner? Who's ranting? Are you talking about one of the commenters?

@J. W. Brewer

"…Prof. Mair's overall scrap-hanzi-for-pinyin agenda…."

You must be talking about some other Prof. Mair. I am an advocate of phonetic annotation for educational purposes and for digraphia as appropriate in other contexts. So that you and others do not continue to misrepresent my position, I wish to state emphatically that I do not advocate the abolition of characters.

J. W. Brewer said,

May 18, 2011 @ 3:30 pm

I regret mischaracterizing Prof. Mair's position. Would reduce-current-level-of-hanzi-dominance-while-increasing-pinyin-usage agenda be fairer? It may be that when someone is pushing against the status quo it is sometimes more obvious which direction they are pushing in than how far in that direction they intend to go before stopping.

And as to rivers4, Prof. Mair is obviously one of the subset of foreigners who have already incurred massive sunk costs and successfully mastered a vast number of hanzi, which (in the appropriate professional field) gives them a quite considerable advantage over other foreigners dealing with matters Sinitic. So it ought to be noted to his credit that his reform proposals may cut against his own narrow self-interest.

minus273 said,

May 18, 2011 @ 3:54 pm

>> The owner of this business, for whatever reason, wants to use the character 旻 in the name of their clinic.

Either the owner thinks that there is a particular beauty/sense that doesn't exist in homophones ( 民、珉 and whatnot), either that is his/her own name, which comes from a similarly conscious choice of their parents. Frankly I can't see why it's a script fail here, as it's obviously more enabling than disabling.

Joshua said,

May 18, 2011 @ 9:40 pm

Dan T.: I note that Sade's record company failed to take into account the fact that most U.S. speakers have rhotic accents, and, consequently, many of them (including myself) wound up pronouncing the "r" sound in "shar-day", which was never meant to have been pronounced. For the American market, they should have said "pronounced shah-day" instead.

bryan said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:26 pm

Mín 旻 consists of two simple components, rì 日 ("sun; day") and wén 文 ("pattern; character; script; writing; culture"), either one of which might serve as a semantic classifier ("radical") in various characters, but in mín 旻 it is rì 日 that is the semantic classifier and wén 文 that is the phonophore (N.B.: Cantonese man4 man6; Taiwanese bun [in a disyllabic word] or buun [by itself]).

What is the phonetic here? Is the dictionary pronunciation of 玟 wen or min?

In Cantonese, 文 & 民 are pronounced the same. So in Middle Chinese, the pronounciation might have had 文 / 民 as a phonetic, but in Mandarin, they're pronounced differently: 文, wen vs. 民, min

bryan said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:30 pm

why not quietly abandon it and switch to a phonetic alphabet already in use?

Actually we can see what happens when a language abandons Chinese characters in favor of a phonetic script. This is the difference between Korean and Japanese.

Totally wrong. Ever thought about what happened to Vietnam? Most of the words are now untraceable to its Chinese origins if the incorrect accent in Vietnamese is used via the useless Latin alphabet.

[(myl) The ratio of content to invective in your comments is dangerously close to zero. This one contains a small factual claim (that Vietnamese orthographic reform led to loss of knowledge of Chinese etymology — presumably among the tiny fraction of Vietnamese who ever learned the Hanzi-based system), but several of your other comments contain nothing but insults, and I've therefore deleted them in accordance with our comments policy.]

bryan said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:34 pm

That said, I quite like bopomofo (perhaps because of my youthful exposure to kana in Japan, although for all I know the Japanese parallel is actually a negative in China for political/historical reasons), and would be happy if Prof. Mair could convince the Communist regime on the mainland to scrap the ungainly Hanyu Pinyin in favor of an elegant phonetic-script solution that was actually custom-designed to fit the phonology of Mandarin.

Why ask anyone else to do your dirty work? Do it yourself!

Pinyin, like Wade-Giles and Yale, and bopomofo, which appropriately as you don't know is called Zhuyin Fuhao, are just that: approximations via the Latin alphabet. It could never be exact: The Chinese script wasn't made to be romanized or used like an alphabet from the start!

[(myl) You obviously feel strongly about this matter, but that doesn't excuse your failure to read the post that you're criticizing.

You write: "…bopomofo, which appropriately as you don't know is called Zhuyin Fuhao".

The post: "These are informally called "bopomofo" after the first four sounds of this phonetic system (a semisyllabary plus tonal diacritics), which is somewhat more formally referred to as Zhùyīn fúhào 注音符號 (Phonetic Symbols)."

Neither does your passion excuse your ignorance of the nature of writing systems and their relationship to languages.

You write: "Pinyin, like Wade-Giles and Yale, and bopomofo, … are just … approximations via the Latin alphabet. It could never be exact: The Chinese script wasn't made to be romanized or used like an alphabet from the start!"

But all writing systems, including logographic systems like Hanzi, are approximations of spoken language that "can never be exact". Different choices are inexact in different ways.]

Bathrobe said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:42 pm

>>Ever thought about what happened to Vietnam? Most of the words are now untraceable to its Chinese origins if the incorrect accent in Vietnamese is used via the useless Latin alphabet.<

Well, the bigger picture is, has it done the Vietnamese any harm? When they ditched Chinese characters, there was obviously a component of choosing to cut off Vietnam's links to the glorious Chinese tradition. Obviously there are trade-offs, since being tied to Chinese characters to understand or create vocabulary has its pros and cons.

Victor Mair said,

May 18, 2011 @ 11:56 pm

@bryan

"…bopomofo, which appropriately as you don't know is called Zhuyin Fuhao…."

Read my post.

YT said,

May 19, 2011 @ 2:44 am

I didn't recognize the character 旻. My first thought was that the 注音符號 may be for the Taiwanese pronunciation of the character.

I looked up 旻 in my 國語曰報辭典. It's in there, but there aren't any 辭, just one sentence explaining that 旻天 is the same as autumn day.

I wanted to add that 國語曰報 is geared towards schoolchildren. 注音符號 is used only in elementary school as a tool to learn characters, so in that case it is like furigana.

minus273 said,

May 19, 2011 @ 4:16 am

@Bathrobe: As a usual defender for the Chinese characters, I nevertheless heartily welcome our Vietnamese overlords to take over our character usage. With a super-distinctive Romanization like Vietnamese pronunciation of Chinese characters, the beloved current literary language with its piles of Classical borrowings and initialisms.

minus273 said,

May 19, 2011 @ 4:17 am

can be kept intact.

Bathrobe said,

May 19, 2011 @ 4:44 am

I think that bryan is coming from a completely different angle on this.

>>"Pinyin, like Wade-Giles and Yale, and bopomofo, which appropriately as you don't know is called Zhuyin Fuhao, are just that: approximations via the Latin alphabet. It could never be exact: The Chinese script wasn't made to be romanized or used like an alphabet from the start!"<

In a theoretical sense, pinyin or Zhuyin Fuhao can be regarded as independent writing systems for representing Chinese. In this sense they are not inexact at all. They represent the sounds perfectly well and could be used without problem to write Chinese.

But in fact, this is not how pinyin or Zhuyin Fuhao are used. In reality they are used not as a means of representing Chinese, but as a means of representing sentences as written in the current Chinese script. The last part should be emphasised. In that sense pinyin and Zhuyin Fuhao ARE inexact, because they lose information that is carried by the current script.

Current written Chinese is in many ways a product of the script it is written in. Change the script and in the long run the written language will gradually change, too. Whether you would regard this as being for the better or for the worse would depend on your values. But change it would. And in this sense, a writing system cannot be described in neutral terms as an approximation of the spoken language. It is more than just an approximation of spoken language; the script itself shapes the form of what it is supposedly "representing".

So in a way, bryan is not really ignorant of the nature of writing systems and their relationship to language at all. He just has different assumptions, and those assumptions are not necessarily incorrect.

Victor Mair said,

May 19, 2011 @ 5:40 am

@bryan

"What is the phonetic here?"

I had already answered that in my post: "…in mín 旻 it is rì 日 that is the semantic classifier and wén 文 that is the phonophore (N.B.: Cantonese man4 man6; Taiwanese bun [in a disyllabic word] or buun [by itself])."

I've been reading through your numerous comments on this post and on my various posts in the past, and I've discovered that most of what you have to say demonstrates that:

a. you do not read what I've written

b. you say a lot that is totally irrelevant to what is being discussed in the post

Bob Violence said,

May 19, 2011 @ 6:03 am

As a sort of follow-up to Bathrobe's comment: South Korea (unlike the North) never had a top-down script reform abolishing or otherwise limiting the use of characters — the process happened more organically and really took off in the '80s, when there was a growing literary trend towards more colloquial writing incorporating fewer formal Sinitic terms, along with the desire to reach a working-class audience that was never particularly literate in characters to begin with (the excellent film A Single Spark has a pointed scene where a worker has trouble reading the national labor law because of all the hanja). In other words a shift in writing style resulted in a shift in script (from a mixed script with numerous characters to a nearly all-hangul orthography) and that shift in script simultaneously reinforces the new style — of course one can write a formal text in hangul, but it's a different style of formality than one might see in a mixed text from the 1940s or even the '70s.

Victor Mair said,

May 19, 2011 @ 6:28 am

@bryan

This is a typical comment from you:

"Why ask anyone else to do your dirty work? Do it yourself!

Pinyin, like Wade-Giles and Yale, and bopomofo, which appropriately as you don't know is called Zhuyin Fuhao, are just that: approximations via the Latin alphabet."

When I first read this, I simply could not make any sense of it. Now that I am rereading these remarks, they strike me as being motivated by some turbid and unjustified animus. To barely scratch the surface of my consternation, here are a few of the difficulties I have with just these remarks by you (your comments on my other posts are of a similar nature):

a. I have no idea what "dirty work" you're talking about. Do you?

b. Why do you shout at me to "Do it yourself!"? How can I "do it myself" when I don't even know what "dirty work" you're talking about? Moreover, I have not requested anyone to do any work for me, dirty or otherwise.

c. "…Wade-Giles and Yale, and bopomofo… are just that: approximations via the Latin alphabet." I doubt that, among the many thousands of intelligent people who regularly read Language Log, there is a single soul who can comprehend what you are saying here.

As I said at the beginning of this note, this is a typical comment from you. If you wish to continue making comments on Language Log, please be more careful and courteous in the future.

B.Ma said,

May 19, 2011 @ 7:44 am

Hanzi is not an appropriate script for Vietnamese anyway, but the Latin based script was designed to take some dialectal differences into account. This would be impossible to any meaningful extent with current Chinese variants.

The Korean backlash against using characters / mixed script was a reaction against the Japanese, but now more and more Korean youth are taking an interest in Chinese characters.

Anyway, reform of English orthography is nothing to do with reform of Chinese. As the experiment of official simplified Chinese shows, trying to create a new system just results in making a third, even more complicated system.

David Branner said,

May 19, 2011 @ 10:31 am

Certainly there are words that many people pronounce incorrectly in English and if I had the nerve I'd furiganize them phonetic underscripts to rectify things. Except most people can't read IPA.

Recently a foreign-born scholar, someone with a profound appreciation of language, asked me what the correct pronunciation of "genre" was.

I had to tell him there was none.

Bathrobe said,

May 19, 2011 @ 10:44 am

@ Victor Mair

bryan has his own axe to grind. He's basically anti Victor's stance on Chinese characters. It raises his hackles and causes him to make nasty comments.

I think it's possible to look beyond the personal remarks and see that he does have a point of sorts (as I tried to show above) — expressed horribly and illogically, but still a point. It's an emotional subject for some, so emotional comments can be expected, but matching emotion with emotion is not the way to go. The article sets out its arguments clearly and logically. If bryan can't argue his case coherently, then he is only letting himself down, and no skin off Victor's nose.

David Branner said,

May 19, 2011 @ 10:47 am

In a last-minute proofreading project on a volume dealing with language, I corrected the pronunciations of two rare characters that appear in the names of bronzes:

David Branner said,

May 19, 2011 @ 10:51 am

Sorry – this post got truncated at a high-codepoint Chinese character. It was visible in the preview but vanished in the post, taking most of my prose with it. I'm reposting now with a substitute:

*****

In a last-minute proofreading project on a volume dealing with language, I corrected the pronunciations of two rare characters that appear in the names of bronzes: [旡+可: http://www.unicode.org/cgi-bin/refglyph?24-23130%5D (Hànyǔ Dà Zìdiǎn 2/1147 "ě"; Lóngkān shǒujìng fq 無可反 actually gives "mǒ") and 琱 (琱 var. 雕).

A colleague declined to accept these. Everyone pronounces them He and Zhou, he says. (Actually, I find that "diao" is common in published sources.) What really bothers me is that he has no idea what it means for a reading to be correct or incorrect. He is an immensely learnèd and insightful scholar, but for him words are like used eggshells. So much for my Fabergé collection.

He's not alone. The whole of sinology seems to be dominated by people for whom language issues are non-existent or unimportant.

Bathrobe said,

May 19, 2011 @ 11:04 am

Sounds to me like he himself had the wrong idea about how to pronounce them and resented being enlightened by a foreigner. Tell us when you find a true gentleman and scholar among these 'learned' types you know.

army1987 said,

May 19, 2011 @ 12:31 pm

Doesn't the General Chinese orthography by Yuen Ren Chao cover all major dialects already?

David Branner said,

May 19, 2011 @ 3:37 pm

@army1987: I'm sorry to say that the major dialect groups are not representable by a single metasystem, unless you're writing a purely literary form of Chinese in them.

Nicki said,

May 19, 2011 @ 8:35 pm

About 旻: As I was choosing my Chinese name I was looking for a name character pronounced "min" (any tone was acceptable for me). I considered 旻 as it had a pleasant meaning, as well as being a character more commonly used in names. However I eventually went with 敏, as it was much more common overall and a fair few of my Chinese friends didn't know 旻.

Ethan said,

May 20, 2011 @ 1:33 am

國語日報 is definitely great for Chinese learners; at my urging, my university's East Asian Library started ordering it last year. Given the lack of interest in traditional characters on the part of today's Chinese students, however (myself included), I don't expect it to be put to much use.

I also agree with Professor Mair's comment about the excellent published materials available in Taiwan. I was given a fantastic 古文-普通話-English version of Confucius's Analects a few years ago, and I treasure it.

Colin Z said,

May 20, 2011 @ 2:48 am

"I'm sorry to say that the major dialect groups are not representable by a single metasystem, unless you're writing a purely literary form of Chinese in them."

@David Branner: Could you further explain this comment? Do you mean that you can't/shouldn't include certain dialect groups eg Min, or modern dialects have too many dialect-specific morphemes, or something else? Didn't the Jerry Norman system in your rime table book do a reasonable job of incorporating a range of dialects?

@David Branner, John Cowan, or others: How feasible is diasystemic spelling for Chinese? Has anyone out there actually succeeded in learning one of the systems that's out there and being able to decipher Modern and/or Classical Chinese passages written in it?

Ray Dillinger said,

May 20, 2011 @ 12:20 pm

The problem with substituting something else for the Sinograms is that they are used to represent several different languages (called "dialects"). Each language is represented imperfectly, however. Idiomatic phrases in particular do not have currency across dialects. Most dialects have different rules about how to construct sentences in informal speech. And of course the pronunciations of different words/characters varies across dialects in such a way that there is no consistent mapping of character to pronunciation that is valid across them.

Using the Characters, you can write something very formal, artificial, and archaic-sounding that will be read with the same meaning across dialects; but you cannot write any approximation to modern and casual idiomatic speech that will be comprehensible in more than one or at most two.

Now, the Chinese Government's response to this has been to bury its head in the sand and try to pretend that dialects other than Mandarin don't exist. Or to actively try to discourage the use of other dialects. Perhaps as an encore they could forbid the sun from rising in the east, and then refuse to acknowledge it when it does.

Losing the "Universality" of the Characters would be a huge loss for Chinese nationalism; if you actually had a writing system that reflected pronunciation, then you'd have to write the dialects completely differently. In so doing, you'd lose a major part of the ability to pretend that the Chinese are a unified people with a common heritage.

John Cowan said,

May 20, 2011 @ 12:34 pm

Colin Z: The other Sinitic languages do indeed have too many language-specific morphemes in them, which are not used in literary style precisely because there are no characters for them.

David Banner: With respect, that seems a tad unGricean of you. Given a bit of time, I would have looked in a few current dictionaries, and said that [ˈ(d)ʒɑnrə], [ˈʒãrə], [ˈ(d)ʒɒnrə], and [ˈʒɒ̃nrə] were equally correct. In more haste, I would have given him my own pronunciation, [ˈʒɑnrə], with the disclaimer that while it was not the correct pronunciation, it was certainly not incorrect.

John Cowan said,

May 20, 2011 @ 12:34 pm

Sorry: please ignore the [n] in the fourth transcription.

David Branner said,

May 20, 2011 @ 12:42 pm

@Colin Z: The problem is that although you can easily represent most of the morphemes that are shared by the traditional written language and the major dialect groups (I reserve "dialect" for an individual regional or social variety, regardless of its exact classification), you can't meaningfully represent words and morphemes that are local to one or another dialect group. Jerry Norman's CDC represents only morphemes of the first kind — those shared by the written language and the major dialect groups. You can't easily represent local or "characterless" words unless you can show that, in comparative terms, they can be assigned to a consistent place in the CDC or medieval systems.

Since spoken language in actual use almost never lacks local words, you would be limited to writing a highly literary form of Chinese — something that could by definition just as easily be written in standard characters. You would not be writing "dialect" — you would be writing literary Chinese or Mandarin as read in dialect pronunciation.

Earlier in the rime table book where Jerry Norman's CDC is first presented, you'll find a paper I wrote called "“Some Composite Phonological Systems in Chinese” (The Chinese Rime-tables, pp. 210-232), which addresses this issue a little — mainly, to review a number of systems that were proposed in the 150 years before Norman's CDC. I placed it right before Norman's paper in the volume so as to give some context to his work.

(Please note that there is an errata list for the book, posted at http://brannerchinese.com/dpb/Branner_Corrigenda_Rime_Tables.pdf . I see I must update its first line.)

David Branner said,

May 20, 2011 @ 1:02 pm

@John Cowan: Rē [ˈ(d)ʒɑnrə], [ˈʒãrə], [ˈ(d)ʒɒnrə], and [ˈʒɒ̃nrə], I gave my colleague the best answer I could. So I think I am well within Gricean strictures.

In all seriousness, I felt he was asking for advice on what to say, not a report on what may be acceptable to someone. The six readings you cite are indeed heard, granting the variation in vowels. And we could increase their number by dealing with the vagaries of French "rə" and syllabic "r" in English.

For myself, I avoid the word "genre" in speech because no pronunciation sounds good to me in ordinary English. I don't regard any of these as "correct" in the prescriptive sense. I would put "genre" in a class with "chimera" and "contumely", two other words I use in writing but try to avoid having to say.

Colin Z said,

May 21, 2011 @ 5:50 am

@David Branner: Thanks for your comment. Do you see the dialect-specific morpheme problem as insurmountable? Yuen Ren Chao seemed to address this problem (for Standard Mandarin-specific morphemes) in General Chinese by inserting such morphemes into his broader scheme according where it made sense to put them. (I can't remember what his actual criteria were, but I think that he implied that it wasn't hard to find a home for them even if this might require some amount of arbitrary decisions being made.)

This is not to say that I'm advocating replacing hanzi with CDC or the like. My sense is that this would be practically unfeasible. The early attempt to adopt regionally neutral Mandarin as the national standard was an utter failure, and even though it's easier to tinker with orthography than spoken language, CDC would face some of the same problems. It might be impossible to motivate the majority of Mandarin speakers to learn complex orthographic conventions on behalf of Southerners. Also, unlike moving from traditional to simplified characters, the transition would be completely intractable from the perspective of adult acquisition and thus require an extended period of digraphia.

At any rate, despite the above problems, I'm still interested in the theoretical workability of a CDC-like system. If it actually were possible to write a wide range of dialects in such a system, then my feeling would be that it would have a strong claim to being the theoretical best possible writing system for Chinese. But it sounds like you are saying that this is simply not possible?

David Branner said,

May 21, 2011 @ 12:35 pm

@Colin Z: Right. Even granting a solution to the mechanical issues (doublets etc. for phonologically incompatible forms), you'd be transcribing the regional accents of the written language, rather than the spoken languages. Think of liturgical Latin transcribed in the various Romance pronunciations, rather than the Romance languages themselves.

The characters are already basically adequate for representing the written language; that's the one thing they're pretty well suited to.

T said,

May 22, 2011 @ 9:22 am

Regarding the original topic, here's what I enjoyed with my dinner today:

https://docs.google.com/leaf?id=0B1soEFosP-OuNDU1Yjg3NzQtYzE0ZC00YmNmLThkNDEtMTFmMTEyZTBlZjlk&hl=en_US

Next to 聶 is its bopomofo pronunciation, apparently it's even part of the branding. I think this phenomenon is actually a lot more common than I first suspected!

caffeind said,

May 22, 2011 @ 1:27 pm

IPA is increasingly seen on English signs and advertisements and is of course used in dictionaries. One wonders why the English writing system so often needs a separate script for phonetic annotation. After all, English characters are supposed to be able to represent speech, so it seems odd that users need to resort to a separate writing system (IPA) to clarify how a word should be pronounced.

Colin Z said,

May 23, 2011 @ 3:44 am

Thanks for your post. Sorry if I'm about to beat a dead horse here. Do you mean that characters also fail at representing spoken dialect? (I don't speak any dialects other than Mandarin, so I don't have a sense of how well characters work for southern dialects.) If this is your meaning, then I feel this issue doesn't necessarily invalidate interdialectal romanisation, because characters are no better. Could you not still theoretically achieve with an interdialectal romanization (modulo mechanical fudges) anything that you can do with characters? I do not see why one cannot take any morpheme unique to a specific dialect and romanize it a way that will result in readers pronouncing correctly in that dialect. This seems to be what Chao did with General Chinese (applied to standard Mandarin).

David Branner said,

May 23, 2011 @ 8:26 pm

@Colin Z: By all means beat the dead horse; it may yet wake up.

Characters can represent spoken language, dialect or not, as long as there is an agreed-upon way of representing it. People can also learn to read written Mandarin (written in characters) in dialect, in effect translating it as they go. People in active dialect areas usually have no trouble doing this. But there may be expressions that are not equivalent, in which case the reader has to decide whether to be faithful to the printed page or to oral norms. Classically educated Japanese people can even read wényán off the page into Japanese, with the appropriate particles and syntax. But that doesn't mean that what they are reading "is" Japanese.

The point of the Lamasse and Jasmin Interdialectal Romanisation ("RI") was to achieve a diasystemic representation of sound, regardless of the morphemes involved. Using characters for dialects represents morphemes rather than sound. Do take a look at the paper I mentioned — it covers this and other issues.

The problem with both systems is that not all Chinese dialects are perfectly parallel in syntax or lexicon. Written Chinese, even (these days) written Mandarin is pretty much standardized. There is no simple process for reducing true oral language to that form; literacy is required.

You wrote, "I do not see why one cannot take any morpheme unique to a specific dialect and romanize it a way that will result in readers pronouncing correctly in that dialect." But how will they pronounce it in other dialects? And how will speakers of those other dialects know what it means?

Victor Mair said,

May 23, 2011 @ 9:44 pm

Thanks for that great example, T. That's pretty surprising, since 聶 is not very rare. I probably knew it already in the second or third year of my study of Chinese.

Colin Z said,

May 24, 2011 @ 3:01 am

Ok, I think I understand the source of my original confusion. I wasn't trying to claim that somehow through the use of a diasystem one could write something in say Cantonese and that a Mandarin speaker would be able to read it (more than very rudimentarily). As you say, speakers of one dialect would not be able to understand morphemes from other dialects.

The angle that I was coming at this from was to say: what are the superiorities of hanzi vis-a-vis pinyin that ensure that the latter despite its potential benefits will probably never replace the former? The answers that I find most compelling are: 1. While pinyin can be used for baihua Mandarin, it isn't effective for Classical Chinese or classically-influenced formal writing. 2. Hanzi form a single writing system for all written dialects that offers some advantage in (admittedly low) mutual intelligibility over, say, each dialect using its own Romanization scheme. 3. Hanzi have value as a tradition or cultural relic. A diasystem scheme would seem to me to have distinct advantages over pinyin with respect to 1 and 2, and might almost be able to match hanzi on those scores. So my contention is not that a diasystem would be able to overcome the dialect congruence problem any better than hanzi, just that it might be able to match them. (Not having learned one of the diasystems to competency, I do not pretend to be able to back up this claim.)

I read and enjoyed your paper a few months ago at the same time that I read the Jerry Norman chapter, and looked back over it tonight. I found it very useful, but the questions I was still left with were, related to the above paragraph, about the functionality and ease of learning of a diasystem. My sense of General Chinese was that it was not more difficult than English spelling, but certainly no walk in the park. As for whether it allows the same reading speed through classical passages as hanzi, I will not even hazard a guess.

My apologies if I've been playing fast and loose with terminology. When I referred to "interdialectal Romanization" in my previous post I was trying to refer to the various proposed diasystems in general, rather than the Lamasse/Jasmin proposal specifically. Also, yes, my bad for the infelicitous use of the word "morpheme".

Simon P said,

May 24, 2011 @ 8:07 am

I speak Mandarin and Cantonese and it seems to me that Cantonese is the only non-Mandarin dialect with any real amounts of writing to its name (and it's a far, far, far cry from the amount of Standard Chinese used even in Hong Kong). Characters work very well for writing Cantonese. The lack of standardization means that some Cantonese-only syllables get their own characters whereas others borrow Standard characters with the same or similar pronunciation. Often the same syllable is represented by several different characters depending on who's writing. Some, but not many, tend to be written with Latin letters. The way they are written means that anyone who can read Standard Chinese with Cantonese pronunciation, as well as speak vernacular Cantonese, will be able to guess which character corresponds to which Cantonese-only syllable. Thus the system can be widely used despite the fact that there's no formal instruction in it.

There are books researching the original characters that the author believes the syllables originated from, but nobody uses these characters in everyday writing.

Aori said,

June 30, 2011 @ 3:15 pm

@Greg: You wrote

"IMO the Japanese have a better understanding than Koreans do of the etymologies of the (very large) Chinese-based vocabulary in their respective languages. This despite the fact that Korean, compared to Japanese, has a richer phonology that better approximates Chinese pronunciations, and makes more frequent use of Sino-Korean pronunciations as opposed to native-language calques."

I do not see how the usage of the Chinese characters lead to a better understanding of the etymology of a word. Maybe a better ability to map sounds with Chinese characters, but not etymology.

As an example, consider the word "人間", which is common in Korean and Japanese and have the same meaning in both languages. We can pose several questions as to the word's etymology: What is its origin? What is the function of 間 in this context? From which characters does it derive meaning and pronunciation? etc.

It's doubtful that an average literate Japanese is better able to answer these questions than a Korean counterpart.

Moreover, the Korean orthography is not purely phonetic. It reflects the morphology, especially for the sino-corean vocabulary. For instance, "人間" is written "인간" [ingan] despite being pronounced "잉간" [iŋgan], due to the 人-인 間-간 correspondence. Thus it is quite possible to guess the meaning of a sino-corean word, if not the Chinese characters for it. An analogue in English would be the ability to recognise the meaning of the prefix "tele-" without knowing the Greek Alphabet or that the two "e"s are rendered differently in Greek.

Speaking of eggcorns, they also occur in the opposite direction. For instance, there is a hypothesis that the native Korean word "방", meaning "room", was often substituted erroneously with "房", whose approximate sino-corean meaning is "house".