Soon to be lost in translation

« previous post | next post »

In an Op-Ed piece for the New York Times published on May 14 ("Search Engine of the Song Dynasty"), Ruiyan Xu laments that Baidu (Roman letter name of the popular Chinese search engine ["the Chinese Google"]) is not as meaningful as 百度 ("hundred times," pronounced Bǎidù), which was taken from a poem written more than eight centuries ago about persistent searching amidst chaos ("Search Engine of the Song Dynasty", 5/14/2010):

BAIDU.COM, the popular search engine often called the Chinese Google, got its name from a poem written during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The poem is about a man searching for a woman at a busy festival, about the search for clarity amid chaos. Together, the Chinese characters băi and dù mean “hundreds of ways,” and come out of the last lines of the poem: “Restlessly I searched for her thousands, hundreds of ways./ Suddenly I turned, and there she was in the receding light.”

Baidu, rendered in Chinese, is rich with linguistic, aesthetic and historical meaning. But written phonetically in Latin letters (as I must do here because of the constraints of the newspaper medium and so that more American readers can understand), it is barely anchored to the two original characters; along the way, it has lost its precision and its poetry.

Finding many of Ms. Xu's claims to be highly dubious, some to be rather troublesome, and yet others to be downright annoying, I decided to try to determine what might have prompted her to make them.

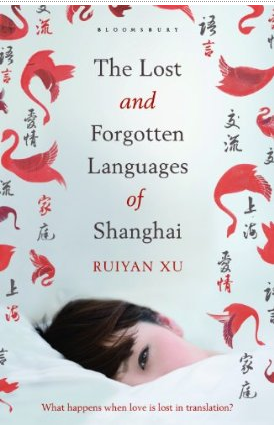

Noticing at the conclusion of her essay that Ms. Xu is the author of the forthcoming novel The Lost and Forgotten Languages of Shanghai, I became all the more intrigued. This, I thought to myself, clearly has the makings of a Language Log post. Since the novel (to be published by St. Martin's Press), won't be out until October of this year, I couldn't go out and read it at once, but I was able to find out a considerable amount about it.

First of all, the cover, pictured below, simply floored me.

Never mind that beautiful eye staring out from a white background, nor all those untranslated Chinese words ("language," "exchange, associate with, make friends," "Shanghai," "love," "family") scattered about, nor yet the red, swooning swans tumbling down the page. What really stunned me was the question at the bottom: "What happens when love is lost in translation?"

"Lost in translation" is my bread and butter, but I didn't have any good answer to the question. I was stumped. I didn't even have the beginning of an answer.

Fortunately, I was able to find a summary of the plot:

Li Jing, a high-flying financier, has just joined his father for dinner at the grand Swan Hotel in central Shanghai when, without warning, the ground begins to rumble. It shifts like a pre-historic animal, then explodes in a roar of hot, unfurling air. As Li Jing drags his unconscious father out of the collapsing building, a single shard of glass whistles through the air and neatly pierces his forehead. In an instant, Li Jing's ability to speak Chinese is obliterated. After weeks in hospital, all that emerge from his mouth are unsteady phrases of the English he spoke as a child growing up in Virginia. His wife, Zhou Meiling, whom he courted with beautiful words, finds herself on the other side of an abyss, unable to communicate with her husband and struggling to put on a brave face – for the sake of Li Jing's floundering company, and for their son, Pang Pang. A neurologist who specialises in Li Jing's condition – bilingual aphasia – arrives from the US to work with Li Jing, to coax language back onto his tongue. Rosalyn Neal is red-haired, open-hearted, recently divorced, and as lost as Li Jing in this bewitching, bewildering city. As doctor and patient sit together, sharing their loneliness along with their faltering words, feelings neither of them anticipated begin to take hold. Feelings Meiling does not need a translator to understand.

This plot does have connections to long-standing issues in language pathology. "Ribot's rule" (Théodule-Armand Ribot, Les maladies de la mémoire, 1881) asserted that the language learned earliest in life is the first to recover from brain injury. This principle was supported by Freud (Zur Auffassung der Aphasien, 1891), who argued that a lesion would never affect a native language while while sparing the "superimposed pattern of associations" in a language learned later. But Ribot's rule was challenged by Pitres (Albert Pitres, Etude sur l'aphasie des polyglottes, 1895), who cited clinical cases where the rule did not hold, and proposed instead that the language to recover first would be the one that was most familiar and most used prior to the injury, since it would have the most solidly established pattern of cortical associations. According to Loraine Obler et al., "Brain Organization of Language in Bilinguals" (in Ardila and Ramos, Eds., Speech and Language Disorders in Bilinguals, 2007), Krapf (1957) cited cases where neither Ribot's rule nor Pitres' rule applies, and suggested that "the patients' personal situation prior to lesion onset and the emotional significance of the various languages in the patients' life history would influence how patients' languages recover from aphasia". And the accumulation of case studies has continued to the present day: perhaps the fictional Rosalyn Neal will get a publication out of it, whatever happens to the feelings.

Since Ms. Xu (who was born in Shanghai) came to the United States at the age of ten, graduated from Brown University, and chose to write her first novel in English, the language loss of the main male character in her novel is in some ways a reverse modeling of what happened to her, except that his loss of Chinese was instantaneous, whereas hers would have been gradual. Ms. Xu states here that she has forgotten how to read Chinese.

This is as far as I got on this post when I became distracted by other pressing matters. It was always my intention to go back and spell out all of the problems I had with Ms. Xu's Op-Ed piece in the New York Times. Now I am relieved that I no longer have to, since Mark Swofford, over at pinyin.info, has just written a masterful dissection: "Chinese characters: Like, wow", 7/2/2010.

Mark has said everything that I wanted to say about Ms. Xu's linguistic point of view, but in a much clearer and more thorough fashion. If you're interested in the Chinese character domain name situation, comparative writing systems, the difference between language and writing, and morphemic homonymy (Mark's treatment of bi, bi-, buy, by, bye and dew, do, due is astonishingly impressive), I invite you to read his essay on Ms. Xu's Op-Ed piece. Oh, by the way, it is long, but there is a wonderful surprise ending.

language hat said,

July 11, 2010 @ 10:44 am

I do not understand the big guns being hauled out to blast this little op-ed by a novelist who makes no claim to being a linguist; I have written about it here. Surely there are more worthy objects of attack out there in the wide world.

Daniel von Brighoff said,

July 11, 2010 @ 11:46 am

I do find Swofford's piece somewhat mean-spirited and nitpicky in spots. (Particular on such issues as the proper rendition of Hanyu Pinyin, since for all we know this was the work of an editor rather than Xu herself.) But on the subject of authority, it does rub me the wrong way that quite a few of the op-ed's readers will be more inclined to believe Xu's claims about Chinese than Swofford's or Mair's simply because she was born with a Chinese surname and they weren't.

It's clear that we have different journalistic standards for the treatment of foreign languages in English-language media. Even so, do you really think it's reasonable for a paper that so clearly aspires to be the American paper of record to publish an op-ed on Chinese characters by someone who can't even read them? And shouldn't the author who presumes to write about a subject so far outside her competence be taken to task for it?

We don't need the big guns for that. But what calibre would you suggest?

TB said,

July 11, 2010 @ 12:31 pm

As usual when Chinese characters are discussed on LL, I am made to feel like a sentimental fool. I suppose these experiences teach me a valuable humility for those times when I feel superior for actually knowing what the passive voice is. I certainly roll my eyes when people act like Chinese characters have a deep mystical meaning that Latin characters lack, and I suppose this kind of annoyance boils over sometimes if you hear it too many times. But I agree with Language Hat that this seems like a pretty harmless op-ed to me.

ShadowFox said,

July 11, 2010 @ 12:51 pm

"It shifts like a pre-historic animal, then explodes in a roar of hot, unfurling air."

This is almost Dan Brown-worthy. It seems doubtful Ms. Xu was ever in an earthquake or is familiar with exploding buildings. But even aside from that, what does it have to do with a "pre-historic animal"?

Gary said,

July 11, 2010 @ 6:24 pm

To the outsider this seems to be a 暴风雨中的茶杯. (That's how google translates tempest in teacup.)

Urban Garlic said,

July 11, 2010 @ 7:58 pm

I recently ran across a related issue arising from a kind of fetishization of Chinese characters — apparently the idea that these characters somehow convey meaning "more directly" than alphabetic systems was the inspiration for various symbolic-language systems. (I ran across this in Arika Okrent's "In the Land of Invented Languages", highly recommended.)

I'm quite taken by Xu's assertion about Baidu having this marvelous cultural resonance — I didn't know that, and I think ti's pretty cool. But it also seems to me that the Pinyin News article is basically correct in pointing out, from several different directions, that this really is a cultural knowledge issue, not really connected to writing systems as such.

I don't think it's a trivial issue, I think trying to convey implied cultural context is valuable, and is of course the central challenge of quality translation efforts. Think about culturally loaded phrases in English, and how much depth and resonance is easily lost by transliteration — "final solution", say for instance, or "irrational exuberance".

J. Goard said,

July 11, 2010 @ 9:54 pm

@Daniel:

it does rub me the wrong way that quite a few of the op-ed's readers will be more inclined to believe Xu's claims about Chinese than Swofford's or Mair's simply because she was born with a Chinese surname and they weren't.

Not me. I trust her because she's way hotter than they are.

Victor Mair said,

July 12, 2010 @ 12:38 am

Mark Swofford may be a bit of a curmudgeon, but don't we need public consciences to protect us from those who romanticize, exoticize, and distort what they don't understand? And, when it comes to linguistics, are we to let sentiment rule over science?

Comment from one of my graduate students: My response to Language Hat's comments might be that it is fine not to know, but not fine to pontificate at length as if you do on the pages of the NY Times (who should really share some of the blame). The description of the novel's plot, incidentally, was also nausea-inducing.

(Because some of the participants in this debate have commented on two or more of the relevant sites [LL, LH, and Pinyin News; i.e., there is a triangular discussion going on], I am cross-posting this comment to all three sites.)

Steve Harris said,

July 12, 2010 @ 5:45 am

Has no one realized the mystical clarity and precision in the word "google"? 10^100 and all that!

With that off my chest: Am I right in understanding Xu's point (however badly put and inaccurately written) to be the following? There are associations (literary and linguistic) with many uses of Chinese characters that are concealed by use of romanization, so there is Good Cultural Reason to encourage the preservation of Chinese characters in electronic communication of all sorts.

However, accepting the truth of that–which seems eminently sensible–doesn't seem to me to argue much for domain names (though there are surely other good arguments for that, ranging from "this is how I write naturally" to "this is my nationalistic pride"). After all, speaking doesn't induce those literary and linguistic associations any more than using romanization does, and domain names don't strike me as more worthy of serious preservation than ephemeral speech.

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 9:09 am

It's all mostly Greek to me, but readers should note that Mark Swofford blogs out of free and democtratic Taiwan, not communist China. He is well known here.

re: ….. since Mark Swofford, over at pinyin.info, has just written a masterful dissection: "Chinese characters: Like, wow",

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 9:19 am

One thing readers here should note and be aware of: this NYTimes oped piece was assigned to Ms Xu because her agent told the Times oped desk that Xu has a new novel coming out in Octobe and sure would be cool to get a kind of free, unpaid advertorial mentioning the novel's title in the author's ID in the print edition of the Times as a good way to spread news of the upcoming novel's pub date. Capice? This is how the Times does business. Xu wrote that piece for the Times because the Times commissioned it because her book agent asked for it and there it is. These opeds don't just appear magically out of the blue. It is all agenting and marketing behind it all. I know. The Times pretends these pieces are sent in cold, they are not. Every oped in the Times was assigned and commissioned, ask David Shipley there, he will dish. And this oped was not even about her new novel, so why in the world was it assigned to her? Guess. Name awareness. She is now a star, as "published in the New York Times" the early reviews will say. The Times should be more transparent, one, and the public should be more aware of how these oped shenanigans work.

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 9:58 am

@ Daniel von Brighoff …."…..

1. "do you really think it's reasonable for a newspaper like the NYTIMES that so clearly aspires to be the American paper of record to publish an op-ed on Chinese characters by someone who can't even read them?

2. And shouldn't the author who presumes to write about a subject so far outside her competence be taken to task for it?"

1. No.

2. Yes.

The reason the Times assigned the oped had nothing to do with Chinese characters or competence in reading them. As noted above, it was all an inside job, friends helping friends. Some who knows someone at the Times oped desk also knows Ms Xu in NYC and at some party it all came together, probably at her agent's instigation, which means she has a good agent! But this kind of oped assignment ends up dumbing down the Times. Sigh.

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 9:59 am

But hey, the novel might the good, really good, the next JOY LUCK CLUB, so let's give it a chance. As a novelist, I have a feeling Ms Xu soars….

Cleo said,

July 12, 2010 @ 3:01 pm

I've been thinking about what gets lost as Chinese become more international because as an Overseas Chinese, I have firsthand experience with losing components of Chinese heritage with the passing away of Chinese elders who were born at the beginning of the 20th Century but I think it's not too late and it's more important than my great grandmother's recipe for persimmon stuffed mochi. I think that instead of talented energetic people with spare time volunteering at Church soup kitchens, those same talented people like food bloggers can just go out in teams of twenty and influence and spread and continue our complex linguistic traditions. It's not hard and it's a fun project. We just need to conscientiously feed our environment.

C. Scott Ananian said,

July 12, 2010 @ 11:18 pm

@Steve Harris: "google" conveys not just 10^100, but also the vison-related word "goggle". That similarity would also be lost by any transliteration or translation, I bet.

Ultimately you lost something in translation. Thank goodness there are erudite articles you can google to fill in the missing context!

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 11:21 pm

Trying to get to the bottom of this, from the Oped page's viewpoint, to ascertain if editors there were aware the Ms Xu is not a speaker or reader or writer of Chinese, and yet she says she is in the oped, I asked David Shipley at the Times to email me at home. His office mail said: "I will be out of the office and away from email until Wednesday, July 14. If you have urgent Op-Ed business, please contact deputy oped page editor Mary Duenwald at Duenwald@NYTimes.com. Thank you. David Shiplay at Shipley@nytimes.com…." so I've asked her, too. Not to criticize anyone, I am sure everyone was innocent in this unvettting episode, but it's important for a paper like the Times to be aware of such things for future reference. The damage is already done, if damage it was. We shall find out.

Danny Bloom said,

July 12, 2010 @ 11:24 pm

Also, as the Times website says, Ms Xu's oped piece only appeared in the New York City edition of the Times that day, not the national edition. What does that mean? And why only in the local edition, if it was a good oped, why not national edition, as well? Maybe Shipley can explain this later. Maybe the NYC edition is for insiders, locally known, who live in Brooklyn and other nearby areas, and the national edition is for top-flight PHD oped people? The Times is a mystery to me.

Bathrobe said,

July 13, 2010 @ 2:44 am

"I think that instead of talented energetic people with spare time volunteering at Church soup kitchens, those same talented people like food bloggers can just go out in teams of twenty and influence and spread and continue our complex linguistic traditions."

Interesting, but China's complex linguistic traditions are a lot more than just Chinese characters. In fact, I have a sneaking suspicion that an obsession with the culture of the literati will only *hasten* the demise of much of Chinese culture. Much of Chinese culture is 土, that is the largely unwritten folk culture. When the high culture takes over from the low culture, there is a loss as well.

Perhaps a little off the track here, but when I was in Hainan some years ago I was in conversation with a Japanese person involved in bringing Japanese tourists to Hainan. I asked, "Are they just going to soak up the sun and sea? What about the culture?" The answer was, yes, we are also thinking of holding lessons in making jiaozi. I could only think, "Jiaozi??? Jiaozi???? Teaching people to make jiaozi in Hainan???!!!" While making jiaozi may be a nice way of introducing people to Chinese culture, it is completely divorced from the local traditions of Hainan!

In a similar way, I can't help but feel that the victory of the literate culture is a loss for the culture as a whole. The mandarins who worked for the imperial government had their own 'universal culture' that transcended local differences. They were not even supposed to stay in one province too long in case they got too attached to the place (i.e., involved in entrenched power relationships). So local colour for these people seems to have been apprehended as just that, 'local colour' — hoi polloi stuff to be enjoyed before they were whisked off to their next assignment.

Becoming literate in Chinese characters too easily means becoming immersed in one aspect of the culture. It could easily mean learning more about what people wrote in another place a thousand years ago than about your own local area. For example, literati seem to know more about the types of birds (including mythical birds) found in ancient literature than about the real birds flying around in the trees outside.

Just random thoughts.

Bathrobe said,

July 13, 2010 @ 3:19 am

Looking over my last comment, perhaps I should look at a career of writing op-ed pieces. The logic is about as fuzzy as Xu's :)

dan bloom said,

July 13, 2010 @ 8:12 am

I politely wrote a nice note to Ruiyan in NYC about her website and told her that one remark about her work had a typo and maybe correct it later and she did not reply to me or correct it.

It's not a big t*po, and I make t*pos all the time, and I just wanted to help her. But so far she ignores me. Juen should be JUNE, Ruiyan and of course you meant to type that in, but yr fingers touched the wrong notes. Fix. Page will look better that way.

re:

"Juen 28, 2010: Publishers Weekly says "The Lost and Forgotten Languages of Shanghai" is promising debut.

[Promising Fiction Debuts]"

TB said,

July 13, 2010 @ 12:50 pm

Dan Bloom, do you not realize how threatening your creepy condescending stalkery e-mailing is? Leave her alone.

Dan Bloom said,

July 14, 2010 @ 4:16 am

@TB said,

"Dan Bloom, do you not realize how threatening your creepy condescending stalkery e-mailing is? Leave her alone."

TB, I have no idea who you are but if you want to email me you can find me in the phone book at danbloom gmail acct. I see your point of view, but on the other hand, you might also look at what I did, and many people have thanked me in the past for this exact kind of proofreading help on their blogs and websites, and see that I was actually helping a fellow author present herself better on her website. Since when did friendly proofreading become stalkery? I have been thanked many more times than spanked, but I can see how you might have seen it that way. I don't mind your remarks. But email and find out that I am not creepy or condescending to anyone. Ms Xu is a colleague.

Nijma said,

July 14, 2010 @ 11:16 pm

The logic is about as fuzzy as Xu's

Not at all, Bathrobe. I enjoy cultural vignettes about language (and about medieval Chinese poetry) as much as some people enjoy leafing through the OED. Some days you need 8X10 glossy photos with circles and arrows on the back (à la Alice's restaurant); other days you just need to stop and smell the flowers.