Please be careful

« previous post | next post »

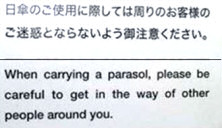

Not only are the stereotypical Japanese fastidiously clean, they are also extraordinarily polite. They will not just tell you to be careful not to endanger yourself. They will be sure to preface the warning with a "please" (actually the word for "please" in Japanese, KUDASAI, comes at the end of the sentence).

In today's Japan mail (from Kathryn Hemmann) come two signs, one warning, "Please Be Careful to Strong Sunlight" and the other, "Please be careful to traffic."

The first example utilizes the intriguing device of a sign within a sign, and it is all in English.

The second example in Japanese reads KURUMA NI GO-SHUGI KUDASAI (car with-regard-to [honorific]-pay-attention please; please pay attention to the cars / traffic).

The consistency of usage leads me to suspect that this may be an established pattern in Japanese translations into English. And using "be careful to" in order to mean "be aware of the dangers of" can create odd results, even when what follows is a verb phrase rather than a noun phrase (from here):

Indeed, "Please be careful to forget valuables" won the 2005 Sign Language Award of the English-Speaking Union of Japan.

And there are many web site warnings along the lines of "This is a scratch site, then please be careful to lose your way."

Chris Kern said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:26 pm

注意 is actually "chuui" in Japanese, but I think your point is good — generally prepositions are a big problem for Japanese studying English (and probably for many studying English), so the difference between "of" and "to" is not so apparent. Especially since the particle に maps to a number of different English prepositions depending on the exact context (just off the top of my head, it can be "to", "for", "on", "onto", "of", "under", "towards", "from", and probably many others.)

kuri said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:30 pm

"The second example in Japanese reads KURUMA NI GO-SHUGI KUDASAI "

That should be "go-chuui."

"The consistency of usage leads me to suspect that this may be an established pattern in Japanese translations into English."

"Ni" is correctly translated as "to" in some usages (e.g., "ni iku" — "go to" or "ni ageru" — "give to"), so the translators probably extrapolated that it can always be translated that way.

Jongseong Park said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:34 pm

I think it's a bit misleading to think of kudasai as merely 'please'. In English, 'please' is a word you can add optionally to requests. Leaving it out will preserve the meaning of the request.

But in Japanese, the standard form of a request will use a conjugation of the verb 'give', and one automatically has to make a choice of speech level to use. By convention, the humble form kudasai seems to be used. Kudasai can't be simply left out; one can only choose to use a different form, like kureyo, which will appear less polite. Note that I'm guessing based on similar usage in Korean; those who actually speak Japanese can correct me if I'm wrong.

mae said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:35 pm

I have also observed a confusion between "put" and "get" in idioms like "get something in your eye" vs. "put something in your eye." Combined with the problems about "be careful" it results in some scary advice.

Chris Kern said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:44 pm

Jongseong: In many cases you can leave out kudasai to simply make the request more direct and less polite (i.e. "kore wo shite kudasai" vs. "kore wo shite"; both mean the same thing but the former is more polite).

In this case, it's not a literal request but just a polite way of framing a warning; I believe that dropping the kudasai here would preserve the meaning in a more clipped/casual form but I'm not 100% sure of that.

fs said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:49 pm

注意 = ちゅうい = "tyuui" or "chuui", not "shugi", which I'd parse as 主義 (principle / doctrine). 「Xに注意ください」 might be translated as "please use caution when dealing with X". Thus whether X is something the occurrence of which is desired but with which much care must be taken or whether X is something the occurrence of which is undesirable and which care must be taken to avoid, the Japanese sentence would be approximately the same; thus the mistranslations.

Jongseong Park said,

August 25, 2009 @ 12:56 pm

Chris Kern: Thanks for pointing that out. I stand corrected. Now that I think of it, that makes perfect sense in analogy to Korean as well; the whole 'give' ending can be left out for a clipped, direct request.

Jason said,

August 25, 2009 @ 1:05 pm

The standard "please take care" polite request "ご注意下さい" ("go-chuui kudasai") uses go-chuui (with "go" being a polite prefix) as a noun, with "kudasai" being (literally) "I give up to you" and (meaningfully) "I politely request." It's the only verb in the sentence so it's quite necessary to complete the statement.

Chris: You can drop the "kudasai" in your example because the -te form of a verb also happens to be a command by itself (though not a linguistic imperative). Here, "chuui" is just a noun and dropping the kudasai means you have no verb and thus a sentence fragment.

Victor Mair said,

August 25, 2009 @ 1:11 pm

Thanks to everybody who pointed out my slip with 注意 and 主義. The first is ZHU4YI4 in Mandarin and the second is ZHU3YI4. I often experience this sort of interference when going back and forth between Chinese and Japanese. Should have checked.

Greg Morrow said,

August 25, 2009 @ 1:30 pm

It would seem that the problem is that go-chuui is being translated as "be careful", rather than "pay attention". Everything else can remain intact.

Does English have an unusually large preposition inventory? I recall being surprised that French à, covered a wide range of English prepositions. When I found that Japanese ni had virtually the same scope, it seemed to make generalizing how to use both of them a lot easier.

Carl said,

August 25, 2009 @ 2:01 pm

In the example of the sign about the parasol, the translator simply omitted a "not" that *was* in the original. 日傘のご使用に際しては周りのお客様のご迷惑とならないように御注意ください is literally, "In the event that you use (honorific) a sun parasol, please be careful (honorific) *not* to become a disturbance (honorific) to surrounding guests (honorific)." Whoever wrote down their translation may have just left out the "not" by accident.

One interesting point about Japanese is that the excessive number of honorifics can be thought to fill in the ambiguities that come from their omission of pronouns commonly used in English and other European languages. "Wait, are they talk about one of their people using a parasol? Ah, no, it's honorific, so they must mean my parasol…"

Timothy Martin said,

August 25, 2009 @ 5:25 pm

Jason: Yes, but Japanese cares far less about having "complete sentences" than English does. Regarding verbs specifically, many times they are simply implied. It's true in the set phrase for "Have a Happy New Year!" ("yoi o-toshi wo!") in which the verb "have" (in this case, "mukaeru") is implied, and it's true in sentences that Japanese speakers spontaneously elicit, such as "tadashi, hitotu dake go-chuukoku wo" ("However, there's one thing I'd like to warn you about"), in which the verb "warn," as well as the "I" and the "you" for that matter, are implied.

Regarding the "chuui" example, it would be perfectly normal to see simply "kuruma ni chuui" on a sign, without the "go" or the "kudasai." It wouldn't be as formal as the above sign, but it would serve its purpose to warn passers-by of cars, and no one would consider the language in the sign at all odd.

Carl: I think the fact that the parasol example fits the pattern of confusing "in" and "of" is a good reason to believe that that's what happened in this mistranslation. After all, a "not" is a hard thing to forget about.

wren ng thornton said,

August 25, 2009 @ 6:06 pm

@Greg Morrow: I wouldn't say that English has a particularly large (nor particularly small) inventory of prepositions. Rather, English broadly lacks the use of cases to distinguish grammatical roles.

In languages which do use case (e.g. Latin whence the romance languages, and Japanese) there are four to six cases which are most common crosslinguistically. One of these is the dative, which French à and Japanese に both fill. Naturally, the exact situations when a given case is used will vary by language and depending on what other cases are available. Thus, the French dative and the Japanese dative don't map perfectly, but they're more similar than the English equivalents (to, for, at,…).

Interestingly, Japanese has both the standard cases and also an extensive inventory of postpositions. Thus, while に covers the dative and can be challenging to translate, it can often be replaced by more specific postpositions like へ /e/ "to(wards)" or から /kara/ "from" which map better to English prepositions. (There isn't a hard and fast distinction between these categories in Japanese, though.)

TB said,

August 25, 2009 @ 7:46 pm

Prepositions, like articles, are very tricky things that are also, for me, especially unconscious. It took teaching English to Japanese students to make me realize the rather aggressive character of "at" as opposed to "to". "He threw a ball at me" vs "He threw a ball to me", or "The car came at me" vs "The car came to me". I don't think I'd ever have gotten interested in linguistics or come to Language Log if teaching hadn't revealed to me how interesting these things are.

Kenny Easwaran said,

August 25, 2009 @ 10:00 pm

I remember when I was studying math in Hungary, one of the professors was similarly polite. He seemed to have learned that when making statements in the imperative it was more polite if you use "Please". So in his lectures he would say things like "Please let n be an integer." And "Please divide by the common factor and see that…"

Axel said,

August 25, 2009 @ 11:48 pm

@Jason

You have misstaken the directionality of "kudasaru" (the dicitionary form of "kudasai"). "Kudasaru" means "to give/hand down towards me" and with the "-sai" ending it is in fact formally an imperative so the literal translation of "x kudasai" would be "give (towards me) x!".The meaning though, is as you put in your comment.

"I give upwards to you" is encoded by the verb "sashiageru".

Nanani said,

August 26, 2009 @ 1:37 am

It would appear that the basic problem is plugging "be careful" for ご注意 even in situations where "Look out" or "Beware" would be better.

Signs where a "not" was omitted are a different class of error.

Most of these signs will have been produced by non-natives, and they no doubt influence each other. Having seen many bilingual signs that go 注意->be careful it is a likely guess for the next sign maker.

Speaking as part of the industry, I can tell you that simple signs are almost certainly not sent out to professional translators and rarely, if ever, checked by native speakers.

Incidentally my dictionary does -not- give this translation, and neither does ALC.

Alex Case said,

August 26, 2009 @ 7:16 am

In my experience working in Japanese offices, the root cause is usually the impossibility of asking anyone for help (let alone saying you can't do it) when given a task like "Translate this sign". Electronic dictionaries might also share the blame

The interesting thing about "kudasai" that I can never get used to is that it is used to give street directions:

"How can I get to the post office"

"Please turn right. Go straight on and then please turn left." etc.

Graeme said,

August 28, 2009 @ 8:20 am

Mitsubishi Australia ran an ad campaign under the slogan "Please Consider".

(Indeed it launched with teaser ads containing just the slogan; I first encountered huge billboards at the cricket with only that gentle slogan.)

The campaign worked in terms of playing on stereotypes and arousing great curiosity. Company still went bust a few years later though.!

Jordan said,

February 7, 2011 @ 10:54 pm

I read a great book and really easy read called "Making Sense of Japanese" – reading this just reminded me of a section in the book where the author discusses how we often misinterpret Japanese mannerisms and gives the example of a sign he loved to keep in his office – it was essentially the equivalent of "Gone Fishing" but many people found it to be rather presumtuous because it more literally says something along the lines of "the customer forgives that we are closed today"…however, the author is quick to make a great point…how different is this from "Thank you for not smoking"?

The Stupidest Not-Very-Nice-to-Others Parasol Perambulation Prescriptions | stupidest.com said,

August 11, 2011 @ 9:13 am

[…] language log This entry was posted in stupid mistranslations, stupid signs and tagged chinglish. Bookmark the permalink. ← The Stupidest Oceanographic Rumination, Saline Explanation Subsection […]