Supreme Court steps away from fetishization of dictionaries, strikes a blow for usage and practice

« previous post | next post »

Below is a guest post by Jason Merchant:

Yesterday, the US Supreme Court announced its decision in the case NLRB v. Noel Canning, a case that turns on the interpretation of the Recess Appointments clause, Art. II sec. 2, cl. 3 of the US Constitution:

"The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session."

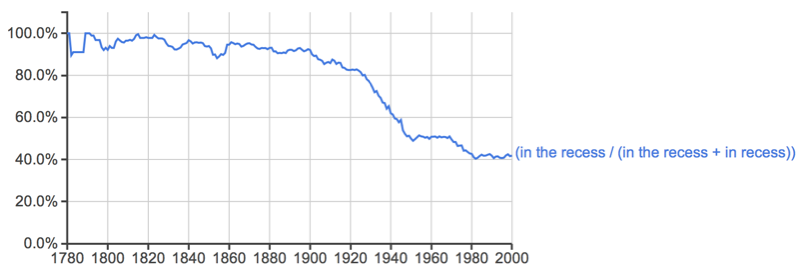

Alison LaCroix and I have argued ("Why the Supreme Court Should Stop Fetishizing Dictionaries and Start Caring About Words", Balkinization 6/20/2014) that the D.C. Circuit Court's ruling in favor of Noel Canning was based on a too narrow reliance on dictionary definitions of the word "the", and that it overlooked the fact that "the" has a range of uses that allow us to take "during the recess of the Senate" to refer to more than just the inter-session recesses, but is also consistent with its use for intra-session recesses (and others): in short, the Circuit Court's analysis of "the" (as imposing uniqueness) is wrong, and fails to allow for generic uses, a point made particularly clearly and with excellent contemporary examples by Neal Goldfarb in "The Recess Appointsment Clause (Part 1)", LAWnLinguistics 2/19/2013). Worse, 18th century usage of the definite article with such nouns shows significant differences from current usage, a fact that must inform constitutional interpretation (particularly for originalist interpreters), but which has gone entirely unremarked upon in the Court's opinion. Using the Google n-gram corpus, we examined the use of "the" with a number of singular nouns with possibly generic usage, such as "the recess" in prepositional phrases, and found that 18th c. usage vastly preferred the inclusion of the article over its omission. For example:

This means, in practical terms, that our modern intuition about the appropriateness of use of the definite article in such constructions is misleading at best, and cannot be taken at face value for an understanding of the Framers' usage.

Fuller details are in our blog post, but the short news for linguists is that the Court has in essence agreed with us: the recesses in question need not be inter-session ones, "the" can be used generically, and may well be so used here, and the vacancies need not have arisen during the recess. (Despite this, the Court ruled unanimously to uphold the Circuit Court's judgment in favor of Noel Canning, but not on the grounds given in the DC Circuit opinion: rather, the Court ruled that the recess in question was too short to allow the President to exercise this power.) But more important, the Court put its foot down and refused to elevate the slavish, narrow-minded reading urged by Scalia et al in their concurring opinion but instead put "significant weight upon historical practice", a direct broadside aimed at the originalist camp, and in line with the argument presented by Eric Posner, "Forget the Framers", 1/8/2014. (More news coverage here.)

There is also much more of interest to linguists in the opinions themselves (and more generally, particularly the rather pointed debate between the two wings of the Court: Scalia calls the majority's decision a "tragedy"), including the nature of restrictive quantification with universals, where the minority opinion authored by Scalia excoriates the majority for essentially ignoring the phrase "that may happen" and accuses the majority of "sweep[ing] away the key textual limitations on the recess-appointment power" (a move that will remind many of Scalia's own strategy in Heller v. DC, where the reason adjunct clause of the 2nd Amendment was reduced to little more than rhetorical throat-clearing, and swept away; see also "The New Yorker finds the U.S. Constitution ungrammatical", 12/18/2012).

Above is a guest post by Jason Merchant.

Bloix said,

June 27, 2014 @ 4:10 pm

So "if you're not careful you'll wind up in the hospital" and "we like going to the beach" are vestigial remnants of 18th C usage?

Mark Stephenson said,

June 27, 2014 @ 6:44 pm

Re "… wind up in the hospital": In British usage, one would say "… wind up in hospital", as a patient; parallel to "in prison", as an inmate.

Mark Mandel said,

June 28, 2014 @ 1:31 am

And also parallel to "in school", as a pupil / student.

John Shutt said,

June 28, 2014 @ 6:29 am

But an unwise investor may end up in the poor house (not, in poor house). Perhaps it has to do with how specific the individual places in the collection are perceived to be?

Dan H said,

July 4, 2014 @ 11:26 am

For modern examples, one might also consider usages like "in the absence of" or "in the event of". These clearly don't refer to *specific, unique* absences or events.