Sinographs written differently on the Mainland, in Hong Kong, and on Taiwan

« previous post | next post »

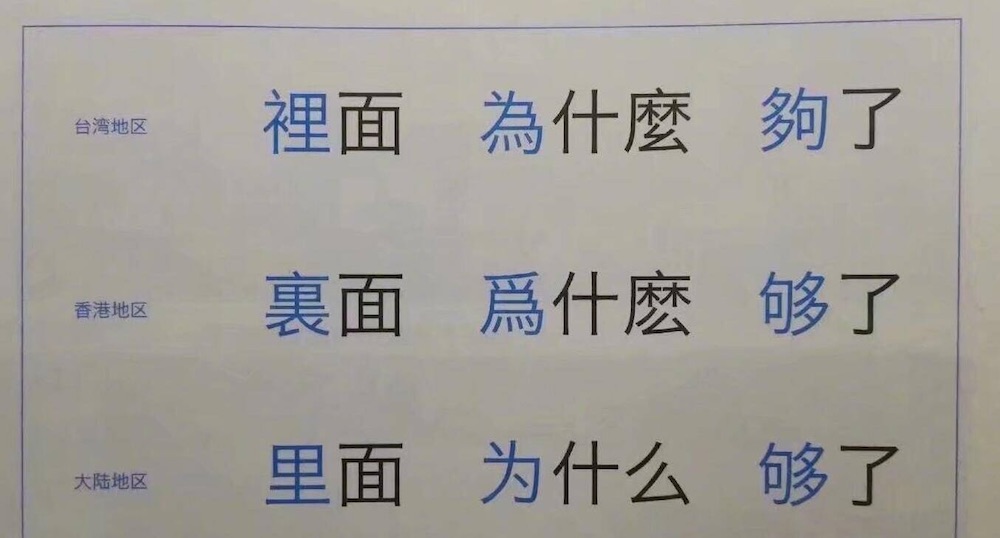

Zeyo Wu spotted this table of variants on the microblogging site Sina Weibo:

This plethora of different Sinographic ways for writing the same words is something that bedeviled me during the very first year of my Chinese language studies half a century ago. I won't get into how kanji are written differently in Japan.

Anyway, even if you don't know Chinese, you can readily see the differences among the characters in blue in the three lines, respectively Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the PRC.

They read (in MSM):

lǐmiàn ("inside")

wèishéme ("why")

gòule ("enough")

Actually, it gets even more perplexing. For example, some Chinese would write miàn 面 ("surface; face; aspect") as 靣, and 面 stands both for miàn ("surface; face; aspect") and the official simplified form of miàn ("noodles; pasta; dough; flour; floury"), whose traditional form is 麵, but was originally written 麪.

This causes lots of problems when one tries to convert automatically from simplified to traditional or vice versa. This is also a major cause of Chinglish mistranslations, especially when you consider that such a common character as that used to write one of the words for "say" is also used to write another common homophonous word, "cloud". In the simplified set of Chinese characters, such instances are legion. This is one reason why I dislike books and articles that cite early Chinese texts extensively but are printed in simplified characters. My Sinology students from the PRC, who grew up knowing only simplified characters, are quite willing to learn traditional characters when writing papers on premodern topiics.

As for the Chinese word for "why", I was first taught to write it as 為甚麼, not 為什麼, and to pronounce it as "wèishénme", not "wèishéme". And my teachers wrangled among themselves over how to write such common characters as xué 學 ("study; learn; imitate") and huì 會 ("meet; can; be able to; conference; association; party"). Consequently, I often just threw up my hands and wrote the requisite morphemes in Romanization.

Antonio L. Banderas said,

March 21, 2019 @ 9:35 pm

Then one must add the issue of different fonts or cursive and simplified handwriting.

Victor Mair said,

March 21, 2019 @ 10:41 pm

@Antonio L. Banderas:

In the case described in the o.p., the different ways of writing particular characters prescribed in different places and by different teachers are considered to be normative, and if you don't write them that way you are wrong. In the cases you mention, those are stylistic, descriptive differences, not prescriptive. They are optional.

Michael Watts said,

March 21, 2019 @ 11:47 pm

Do we know what happened with 够/夠? I thought the mainland simplified characters were intended to reduce characters' stroke counts, but obviously you'll have the same number of strokes whether you put 多 on the left and 句 on the right or the other way around.

The 够 version swaps the halves of the character around so the phonophore is on the left and the semantophore is on the right… which seems weird, because a "regular" character of this form has the semantophore on the left. I think fondly of 切 specifically because it's "backwards" from the norm.

Philip Taylor said,

March 22, 2019 @ 2:25 am

I too thought that "why" was "wèishénme" in Pinyin, and was surprised to see it written otherwise in the article. Thinking that "wèishéme" might be a typo., I asked Google translate and it assured me that "wèishéme" was correct. I will look in Kan Qian's Colloquial Chinese later, but I am fairly sure that it is printed as "wèishénme" there.

Michael Watts said,

March 22, 2019 @ 3:23 am

Yes, weishenme is the standard spelling, but it doesn't reflect the pronunciation.

Chinese appears to have a strong urge towards contractions; there is an even more contracted form of 什么 spelled 啥 shá.

Justin Lo said,

March 22, 2019 @ 3:24 am

As someone from Hong Kong, I don’t think I’ve ever encountered anyone from the city who wrote 為甚麼 and 夠了 in the way shown in the second row. What did baffle me was how all three characters in 為甚麼 there were non-standard.

Chris Button said,

March 22, 2019 @ 5:26 am

I would put the 里/裡/裏 one in a separate category from the other two. The others are essentially variant ways of writing the same thing. Writing 裡/裏 as 里 is taking an orthographic distinction (裡/裏 being but variants again) and merging it as one.

Avinor said,

March 22, 2019 @ 6:00 am

How come Taiwan and Hong Kong have different characters? I thought that the "traditional" ones of both were based on those in the Kāngxī Zìdiǎn?

David Marjanović said,

March 22, 2019 @ 7:23 am

That's what I took away from being taught the spelling and the pronunciation, with no comment on the discrepancy, in the 1990s. (Of course this also holds for shénme "what", where you can at least hear the rising tone that completely disappears in wèishénme.)

Victor Mair said,

March 22, 2019 @ 7:24 am

As mainland norms are being prescribed for education and officialdom in post-1997 Hong Kong, the older forms of the characters previously used in the colony / region will gradually be replaced by mainland standards.

David Marjanović said,

March 22, 2019 @ 7:27 am

(…Of course that, too, is not so simple. The rising tone is in place in contexts like shénme shíhou, "when", literally "what time"; but in zhè shi shénme "what's that", the rising tone is distributed over the whole word, so that -me will simply have a higher pitch than the very reduced shén-.

Pīnyīn generally prefers consistent spellings for morphemes.)

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

March 22, 2019 @ 7:43 am

I have a somewhat tangential question, if that's what you'd call it.

The title of your article is "Sinographs written differently on the Mainland, in Hong Kong, and on Taiwan". The "on Taiwan" part struck me as unusual, as I'm used to locative readings such as "in the U.S.", "in Pennsylvania", "in Allegheny County", "in Pittsburgh", "in the Swisshelm Park neighborhood", and "at my house".

So, I'm wondering if the word choice was a "political" one, i.e., akin to the highly-charged "на Украине" versus "в Украине". If so, the political content of the statement went sailing above my under-informed head. What did I miss?

Ellen K. said,

March 22, 2019 @ 9:09 am

Seems to me "on Taiwan" could be a simply case of not thinking politically, but geographically. Which pairs with "on the Mainland", which is a geographic rather than political description. ("in Hong Kong" can be either.) Taiwan is an island, so "on".

Tom davidson said,

March 22, 2019 @ 9:26 am

And then there are cases in which a father/mother creates a unique character for their offspring, such as 三点水 + 敏 and 女 +美

~flow said,

March 22, 2019 @ 11:05 am

@Michael Watts "what happened with 够/夠? I thought the mainland simplified characters were intended to reduce characters' stroke counts"—that's but one of the objectives of the reform; two more are to reduce the overall number of characters in common use, and to reduce the number of variants. For whatever reason, usage in pre-reform days vacillated between 够 and 夠, so the reformers chose one over the other (maybe the more common form, or maybe the committee did a raise of hands). And yes, unfortunately they opted for the more opaque of the two.

Success Washington said,

March 22, 2019 @ 11:11 am

Actually, for me, a mainland Chinese, I could understand all the three types because that might be the characters in different time, and I feel that mainland might simplify the traditional one (Hong Kong) into simplified one (Mainland) now. For Taiwan type, I did not see it before.

Ouen said,

March 22, 2019 @ 1:26 pm

Like 夠了 to 够了, another confusing simplification is 強 to 强, in this case the simplified character has one stroke more than the standard traditional character. This case is probably as flow explained the case to be with 夠. I think both 強 and 强 are in use in Taiwan.

Philip Taylor said,

March 22, 2019 @ 1:37 pm

Another tangential question. How many readers, on seeing a Hanzi reproduced in a contribution here, and being previously unfamiliar with that Hanzi, could accurately reproduce it without zooming-in one or more times ? I ask because, as someone who does not read Hanzi at anything beyond the absolute basics, I find that at my default magnification / resolution, almost all are too small for me to identify the individual strokes. And this observation is not confined to this forum, but to almost all online sources of Hanzi, and to many printed publications as well, Rick Harbaugh's Chinese Characters: A Genealogy and Dictionary being an extreme case in point.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

March 22, 2019 @ 2:08 pm

To: Phillip Taylor,

Seconded. I'm in a similar situation as you are, but wrt Japanese Kanji. Without previous exposure to the stroke forms, I have to press my nose to the screen to read, for example, 麵, whereas, with stroke forms that I've already had some familiarity with, my gestalt functioning "fills in" the blurry bits, and I can tell that 强, e.g., involves bow and bug and mouth.

Benjamin E. Orsatti said,

March 22, 2019 @ 2:12 pm

P.S. Mastering this infernal writing system can often be quite 鬱陶しい.

Victor Mair said,

March 22, 2019 @ 6:03 pm

With 29 strokes and several possible semantophores, 鬱 is indeed one of the more "gloomy; dismal; depressing; cheerless; miserable" Sinographs around.

pooru said,

March 22, 2019 @ 10:36 pm

a colleague in Ottawa had an interesting mnemonic for how to write the rather complicated 鬱 — he took a line through its resemblance — starry and stripey shapes — to the flag of the republic to the south, to him a source of gloom.

Andreas Johansson said,

March 23, 2019 @ 7:56 am

Regarding the prepositional tangent, to me there's a distinction between "in Taiwan (the country)" and "on Taiwan (the island)". Similarly for Cuba, Iceland, and other island nations.

(People not recognizing Taiwan as a country should not be too upset: I'd also say "in Taiwan (the province)".)

B.Ma said,

March 24, 2019 @ 1:04 am

As someone with some roots in Hong Kong, I agree with Justin Lo that I've never (or so rarely that I doubt it has happened) seen these expressions *written* in the way this Sina Weibo post purports them to be written, however they may be *printed* in this way.

I think 裏 is often used in printed text in HK, but I find it ugly compared to 裡. 裡 is easier to write because you just divide the space into a left and right half, whereas 裏 requires more mental effort, as the 衣 is unequally split (in terms of space needed) and then you have to make your 里 very flat.

I feel that 甚 is the "correct" character used in printed text, but who can be bothered to write 甚 when you can just write 什? I realize the same argument applies to 麼 and 么, but somehow I don't like the look of 么.

As for 夠 I am suffering from character amnesia as I don't recall which way is "correct" to me, both look right. After all, the last time I wrote Chinese with a pen(cil) was probably over 6 months ago.

Regarding Taiwan, the partially recognized country of the ROC does actually have a Taiwan province and Fujian province (though if the PRC were to take control of the ROC, would they merge ROC's Fujian back into PRC's Fujian???).

So "on Taiwan" disregarding the rest of the landmasses that make up Taiwan (when "Taiwan" is used to mean the ROC).

Ronald Tse said,

March 24, 2019 @ 7:32 am

As someone from Hong Kong and educated from its system, I concur with Justin Lo — I have never seen those characters written in such way here.

Sorry to say that this image was created by someone unfamiliar with Chinese usage in Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong 裏 is always taught to be written as 裏.

Everyone has a different opinion on aethetics of characters, the world would be much more peaceful to not impose one's cultural heritage and personal preference to one another.

Victor Mair said,

March 25, 2019 @ 10:39 am

From Fraser Howie:

A question cum sanity check. Surely the biggest split in Chinese lanaguage is 白话 ("vernacular") vs 文语 ("literary; classical"), as opposed to complicated vs simplified. Even with my limited language study, flipping between complicated and simplified is merely exposure, yet classical and colloquial chinese is years of study.

Ronald Tse said,

March 27, 2019 @ 2:27 am

To comment on Fraser's sanity check.

It is probably true that the largest "skill/learning gap" in the Chinese language is the difference in writing of colloquial vs classical (文言).

However, there are many colloquial styles (consider different regional vernacular instantiations throughout history), and similarly the "classical style" is not a singular one (considering how official writing styles have shifted through history).

We might not want to simplify a multi-dimensional question into a binary one.

On the other hand, the question of traditional vs simplified scripts is simpler if the topic is limited to the Modern Hanyu simplification. That said, the simplification of characters is more than just "flipping" — it also leads to conflating of concepts (pigeonhole principle), as demonstrated by Prof. Mair's original post.

Bordering on oversimplification, imagine one day "one" and "won" were written with the same alphabets because they sound similar…