Poetic dynamism

« previous post | next post »

Well, the dynamic range of the amplitude of syllables in poetry readings, anyhow:

What IS that?

In the course of a discussion of other matters, Charles Bernstein asked about measuring and visualizing a poetry reader's variation in amplitude. As I understand it, he has the intuition that some readers are relatively uniform in their presentation, while others are more varied. He mentioned John Ashbery as someone whose readings are on the stable side.

I expressed my usual skepticism about amplitude as a feature. The absolute amplitude of a recording depends on microphone distance and orientation, room acoustics, gain and possible AGC in the recording and later processing, etc. Even within a single recording with no intervention by a sound engineer, a speaker's changes of position and orientation during the performance can have a significant effect. And anyhow, what we perceive as amplitude variations are in most cases really variations in vocal effort, which no one knows how to measure.

But Charles countered that in the circumstances of most poetry readings, there are variations in simple acoustic amplitude that correlate both with the reader's production and the audience's perception. And it ought to be possible to calculate some sort of dynamic range that could be compared across readers and readings.

He's right, and so I thought I'd try it.

What I did:

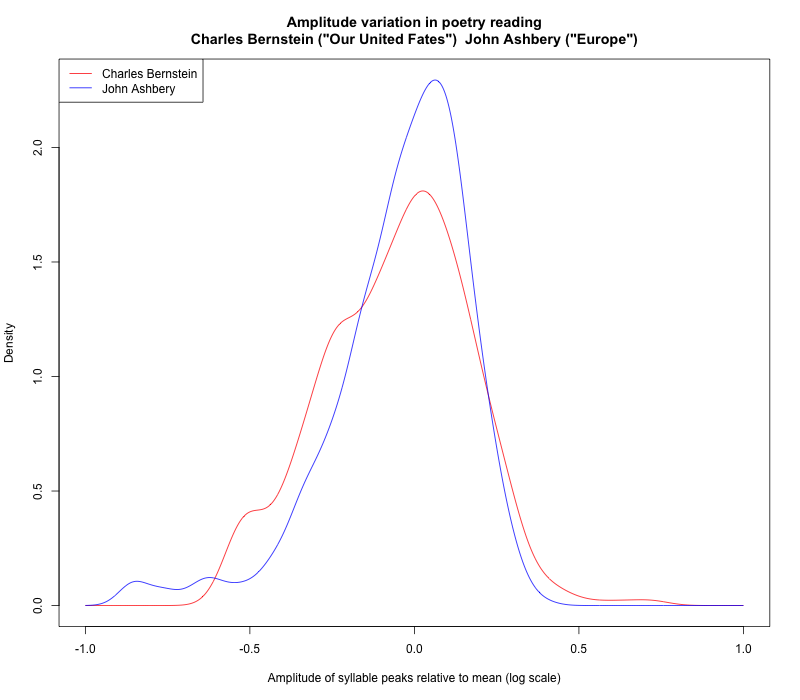

- I took two readings from PennSound: John Ashbery reading "Europe" from The Tennis Court Oath, Sections 1-25, 11/19/2015; and Charles Bernstein reading "Our United Fates", 9/21/2017.

- I trimmed the intro and the outro, leaving just the poems themselves.

- I filtered the audio to roughly the frequency region of vowel sounds, 200-2500 Hz; calculated the RMS amplitude every 5 msec, and smoothed the result with a time constant of about half a syllable; and took all the local maxima above an empirically-estimated noise threshold. The result is a decent syllable-detector, following a simplified version of the recipe in Mermelstein 1975. The result was 1142 pseudo-syllables in the Ashbery reading and 819 in the Bernstein reading and

- To get a normalized version of the "dynamic range" in each recording, I transformed the set of peak amplitude values from that recording to differences on a log scale relative to the set's mean value (log10 of the ratio to the mean value).

- I then graphed kernel density estimates (basically smoothed histograms) of those distributions, as shown above.

(This may not be a great case for contrast; Charles didn't present himself as an especially dynamic reader, but …)

The results:

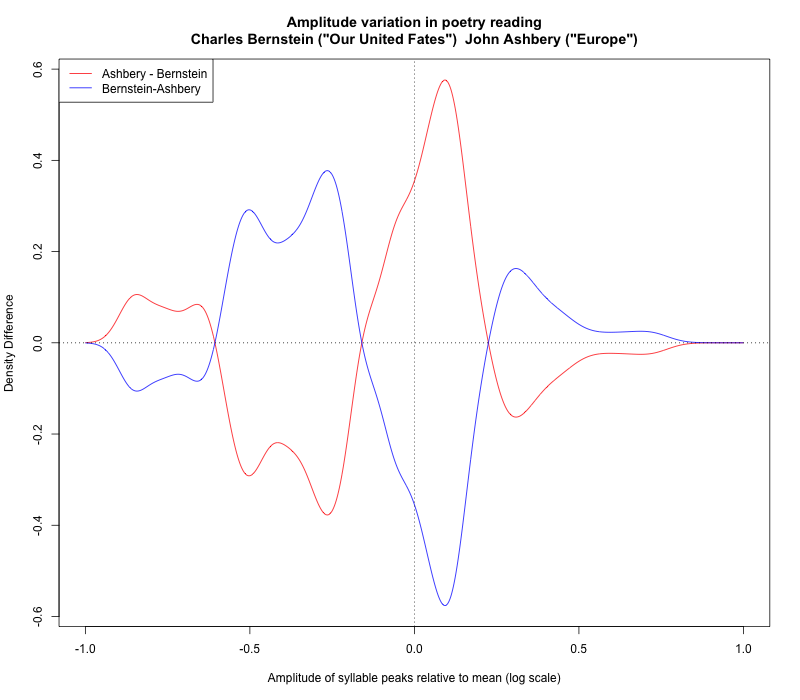

Or we could focus on the contrast, by plotting the difference between the density estimates:

Interpretation:

- Ashbery's syllable amplitudes are more concentrated around the average value, though there are a few lower-amplitude syllables, probably his section numbers

- Bernstein in comparison has a larger number of both softer and louder syllables, relative to his average value

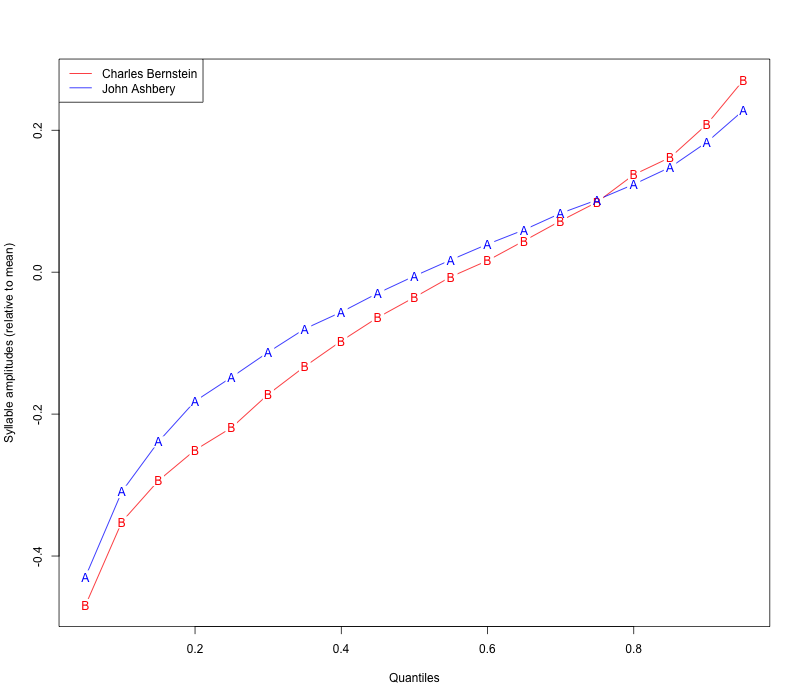

We could also look at the quantiles of the syllable-peak amplitudes, normalized in the same (questionable) way:

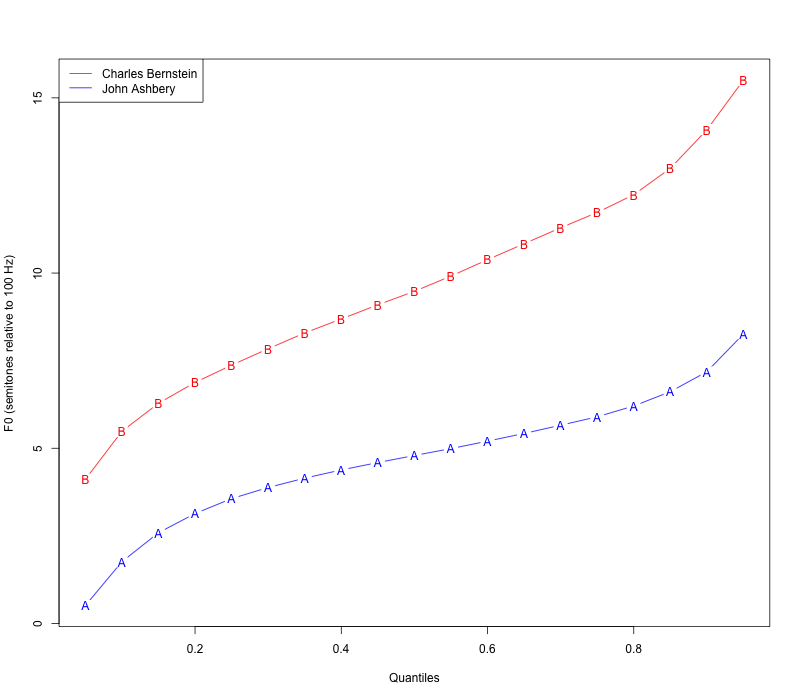

There's an analogous (but more striking) difference in pitch range:

Bernstein's reading has a range (95th percentile – 5th percentile) of 11.4 semitones (across 27726 f0 estimates) — just under an octave. Ashbery's reading has a range of 7.7 semitones (across 47327 f0 estimates) — a bit more than a fifth.

Vance Maverick said,

January 25, 2018 @ 10:22 am

Glad to see this! Ashbery (RIP, a genuinely great poet) indeed had a reputation as a dull reader — and Bernstein, I know from live experience, is not. I was prepared, though, not to see this contrast show up in such basic measurements.

[(myl) It's a gift to be simple — in the sense that simple methods often work surprisingly well.]

Penny H said,

January 25, 2018 @ 12:26 pm

The mention of Ashbery's "reputation as a dull reader" surprises me, as does the recording linked here, because when I was going to a lot of poetry readings in the early 1970s, he was one of the better readers of his own work, and certainly not dull (as well as having a reputation for being quite good-looking).