"I don't have any R's at all. That proves I belong here."

« previous post | next post »

Last night, Connecticut beat Kentucky 56-55 and advanced to the NCAA title game in men's basketball. As a hoops fan who grew up near UConn's campus, I was paying attention. And I already knew that the two coaches, UConn's Jim Calhoun and Kentucky's John Calipari, had a long-standing personal rivalry. What I didn't know, until I read about in during the run-up to the game, was that the rivalry has a linguistic dimension. According to Greg Bishop, "Coaches Calhoun and Calipari share a genuine dislike", NYT 4/1/2011:

Last night, Connecticut beat Kentucky 56-55 and advanced to the NCAA title game in men's basketball. As a hoops fan who grew up near UConn's campus, I was paying attention. And I already knew that the two coaches, UConn's Jim Calhoun and Kentucky's John Calipari, had a long-standing personal rivalry. What I didn't know, until I read about in during the run-up to the game, was that the rivalry has a linguistic dimension. According to Greg Bishop, "Coaches Calhoun and Calipari share a genuine dislike", NYT 4/1/2011:

The contentious relationship between Connecticut’s Jim Calhoun and Kentucky’s John Calipari is perhaps the longest and most entertaining coaching feud in college basketball. It started so long ago that Calipari has held five jobs since. […]

[T]heir first major act of competition […] went to Calipari, then a young, brash hotshot at the University of Massachusetts who in 1993 went to Calhoun’s state and plucked a high school center from Hartford named Marcus Camby. […]

Calhoun considered Calipari an outsider with no background to talk about basketball in New England. He mocked Calipari, calling him Johnny Clam Chowder — pronounced with an “er” at the end, not an “ah” — and not behind his back.

At this point, many readers will need some background on chowders and rhoticity.

The Wikipedia article on clam chowder tells us that

New England clam chowder is a milk- or cream-based chowder, traditionally made with potatoes, onion, bacon or salt pork, flour or hardtack, and clams. Adding tomatoes to clam chowder was shunned, to the point that a 1939 bill making tomatoes in clam chowder illegal was introduced in the Maine legislature. […]

Manhattan clam chowder has clear broth, plus tomato for red color and flavor. In the 1890s, this chowder was called "New York clam chowder" and "Fulton Fish Market clam chowder." […]

The addition of tomatoes in place of milk was initially the work of Portuguese immigrants in Rhode Island, as tomato-based stews were already a traditional part of Portuguese cuisine. Scornful New Englanders called this modified version "Manhattan-style" clam chowder because, in their view, calling someone a New Yorker was an insult.

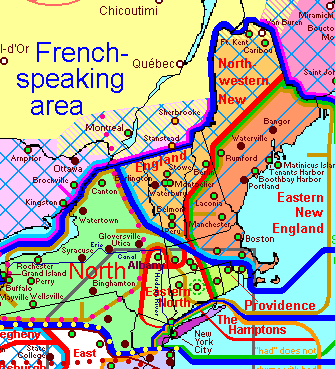

This culinary divide is reinforced by a linguistic one. Speakers in eastern New England share the loss of syllable-final /r/ that took place in southeastern England during the 18th century. The approximate boundary of the r-less region in the northeastern U.S. is indicated by a green line in this map:

The r-less region includes eastern Massachusetts, with the boundary comfortably to the west of Framingham, Massachusetts, where Jim Calhoun was born and raised. The r-less region doesn't come close to including Moon Township, Pennsylvania — in western Pennsylvania near Pittsburgh — where John Calipari was born.

But neither does the r-less region extend as far west as Storrs, where the main UConn campus is located. And Calhoun recruits his players from all over the world — among the contributors to last night's win were Kemba Walker from New York City, Jeremy Lamb from Georgia, and Charles Okwandu from Nigeria. (And rhoticity among African-Americans has a different geography…) So why would Calhoun tease Calipari about his pronunciation of chowder?

We can find a more elaborated version of the story in "The John Calipari vs. Jim Calhoun Clam Chowder Feud", Lost Lettermen 3/29/2011:

There are plenty of reasons Calhoun still holds a grudge against Calipari dating back to Coach Cal’s days at UMass from 1988 to 1996: his sideline theatrics, snagging recruit Marcus Camby from Calhoun’s backyard of Hartford, CT, and preening for the cameras, just to name a few.

But there’s no bigger reason Calhoun can’t stand Calipari than the goading Calipari did when UConn refused to play UMass in a yearly series once the Minutemen landed Camby.

It didn’t matter who was around, Calipari always took an opportunity to call out Calhoun for ending the series. When Calipari came up with the season slogan “Refuse To Lose,” another batch of t-shirts in Connecticut colors read “Refuse To Play.” Students wore shirts that said “UScared.”

Calipari took to the airwaves whenever he got a chance to publicly beg Calhoun to play. But Coach Cal crossed the line in Calhoun’s book when he claimed a Connecticut-Massachusetts series “would be good for New England basketball.”

A big mistake for someone originally from Pittsburgh. To Calhoun, a Braintree, Mass. native, Calipari had no idea what was good for New England. The Massachusetts coach was an outsider who wore expensive suits and his neatly combed hair.

When the press brought up Calipari’s crusade to help New England basketball, Calhoun would quip: “Yeah, Johnny Clam Chowder. Telling us all about New England basketball.”

Johnny Clam Chowder? Yes, you heard Calhoun right.

To a guy from South Boston, there was nothing worse than a fake and that’s what Calhoun thought of Calipari and his forced Boston accent now that he was in nearby Amherst.

Said Calhoun in a sarcastic tone: “He sounded just like a New Englander to me. You could see that clam chowder just dripping off his lips. He never said cah [car] in his life. He used to have an R. I don’t have any R’s at all. That proves I belong here.”

This is a nice illustration of the scale from indicator to marker to stereotype discussed by Bill Labov, e.g. in Sociolinguistic Patterns, 1972. A linguistic change "first appears as a characteristic feature of a specific subgroup", and therefore is objectively an indicator of group identity whether or not anyone pays attention to it. Then "as the original change acquires greater complexity, scope, and range, it comes to acquire more systematic social value" and becomes a marker, which locals recognize at least unconsciously. "Eventually, it may be labeled as a stereotype, discussed and remarked by everyone", including college basketball coaches.

A more complex theory of the same process can found in Michael Silverstein, "Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life", Language and Communication 23(3-4): 193-229, 2003. On Silverstein's theory, if I understand it (as I probably don't), r-lessness has reached at least third-order indexicality in this case.

[I haven't found any independent evidence for the accusation that Calipari accommodated to r-lessness during his time at UMass. And this would have been a bit surprising, I think, since Amherst is in western Massachusetts and (as far as I know) to the west of the relevant isogloss. Does anyone know anything more about this?]

Update — as SteveT points out in the comics below, the chowder-pronunciation issue (like most other aspects of linguistics) has been explored by The Simpsons:

Philip Spaelti said,

April 3, 2011 @ 8:11 am

Yes, Amherst is definitely to the west of the isogloss. But during the school term on campus, eastern dialect pretty much takes over.

Ralph Hickok said,

April 3, 2011 @ 9:00 am

Just for the culinary record, there's also Rhode Island clam chowder, which is simply made with clam broth, no milk or tomato.

[(myl) From a historical point of view, I think that this is probably just a variant of the New England recipe. If we turn to chapter XV, "Chowder", in Herman Melville's Moby Dick, we read that

This takes place in Nantucket, and as you can see, the recipe includes butter but not any other dairy substance.

As for the earlier history, the OED gives this etymology:

]

Anon321 said,

April 3, 2011 @ 9:50 am

I might be misinterpreting Lost Lettermen's account of the "Johnny Clam Chowder" story, but it seems that the two versions disagree over Calhoun's pronunciation of "chowder" when delivering his quip. The Times story says that Calhoun pronounced the final /r/. But the Lost Lettermen story seems to suggest that Calhoun was mocking Calipari for his fake Boston accent — for dropping his final /r/s as a newly adopted affect — and therefore might have pronounced chowder with a sarcastically exaggerated New England accent.

Has anyone here ever heard Calhoun deliver this line?

[(myl) I certainly don't expect accurate quotes from journalists, especially in sports reporting, but I think there's a consistent possibility, namely that Calhoun is accusing Calipari of turning his syllable-final r's on and off to suit the occasion — that is, of being sometimes insincerely non-rhotic.]

GeorgeW said,

April 3, 2011 @ 11:28 am

The important question is, which chowders did the UConn and Kentucky players eat during training? There could be a one-point advantage on the court. Or maybe the rhoticity of the coaches was the difference.

SteveT said,

April 3, 2011 @ 11:46 am

SAY IT RIGHT: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9MlYKMFl_A

Claire Bowern said,

April 3, 2011 @ 12:15 pm

Chowder, rhoticity, Sox/Yankees support and other isoglosses are *very* complex around Interstate 91 in Connecticut, especially around the coast. There is considerable r-lessness in New Haven, for example, but it's conditioned by class and ethnicity too. There's the added complication of the coastal transport network; some NY features make it to New Haven (which is at the end of the NY commuter line) but the coastal towns east of there are also connected (as far as Old Saybrook, if I remember right) by Shoreline East and I95. The line at Old Lyme reflects the difficult of traveling beyond there before the bridge was built (that was the end of the line of trains from Boston). It's one area where drawing a single middle class white line on a map is a really poor way to represent what's going on dialectally.

möngke said,

April 3, 2011 @ 12:53 pm

Silverstein's theory (IF I understand it at all – always a necessary disclaimer when discussing any of his works, as everyone with at least a little background in linguistic anthropology knows very well) states, I think, that a difference between Nth and Nplus1th-order indexicals is that Nth order ones may be an accurate description of sociolinguistic facts (pragmatics), whereas any higher ones are levels of 'meta-pragmatics'. So if pragmatics is a description of language in use (1st order indexicality), metapragmatis (2nd order indexicality) is speakers' PERCEPTION of how language is used, 3rd order is speakers' perception or evaluatıon of speakers' perceptions of language use, and so on, ad infinitum. So I would say the clam chowder debate involves something on the border between second and thırd order ındexıcalıty – between ıt beıng a pure perceptıon of one coach of lınguıstıc patterns, and hıs perceptıon of what such stereotypes MEAN ın practıce (whıch may or may not be shared by other members of the Speech Communıty).

[(myl) Well, the newspaper articles are a report of a statement about the evidentiary status of consistency of adherence to a pattern of language use. So by my count, that's somewhere between third and fourth order. And this post adds at least one more layer, right? Unless layers of talking about talking about things don't count…]

Dw said,

April 3, 2011 @ 1:09 pm

Surely a line separating Sox supporters from Yankee supporters is an isophil :). Or perhaps a heterophil.

Mark Mandel said,

April 3, 2011 @ 1:50 pm

Hey, don't drag the Phillies into this! My wife and I grew up in New York– City, that is.. After grad school at Berkeley we lived in eastern Mass. for 20 years (Brighton [part of Boston], then Marlboro, then Framingham for most of our time there). And now we live in Philadelphia.

So Sox vs. … not Yankees, but Mets, thankyouverymuch … is already complicated enough without adding our current home team into it!

Mr Punch said,

April 3, 2011 @ 3:20 pm

Though UConn does indeed recruit players from all over, this year's team includes three players from Greater Boston – very unusual for a top program.

JMS said,

April 3, 2011 @ 4:13 pm

As Philip Spaelti says, the UMass campus population includes a majority of Massachusettsians from east of the Quabbin Reservoir, so /r/lessness is appropriate for the most local isogloss.

Amherst as a whole is probably not representative of the region (nor is Northampton) because of the many people who came west within Massachusetts and stayed around.

That said, I found that a lot of my brother's friends from other parts of the state and country and globe picked up the highly local feature of using a phoneme midway between glottal stop and flap at the center of words like "mitten", "butter", and "Latin", whereas nobody who came without an r acquired one.

VHC said,

April 3, 2011 @ 4:52 pm

My family comes from Woodstock, CT, approximately 30 miles northeast of Storrs; the town was originally settled by emigrants from Roxbury MA. Until this generation, everyone dropped their R's. I'd be cautious in claiming that Storrs natives pronounce them. All of which is to say that Jim Calhoun might well be hearing real old-line Yankee accents in that part of eastern Connecticut. Geno Auriemma, on the other hand, has a clear Norristown PA accent – do you suppose that's why the two of them barely speak?

[(myl) I grew up in Mansfield Center, another village in the town that includes the village of Storrs. My neighbors and friends included descendents of the original (1692) settlers and a wide variety of more recent immigrants. As far as I can recall, the "old-line Yankees" were no more r-less than anyone else there. Apparently Woodstock had a cultural connection with eastern Mass that Mansfield generally lacked.]

John Cowan said,

April 3, 2011 @ 5:15 pm

Schooner Faire, a folk music group from Maine, has a comic routine about going to New York and being served Manhattan-style clam chowder. The narrator says That's not chowdah, that's spaghetti, or something., distinctly saying neither rhotic /tʃaʊdɚ/ nor ordinary non-rhotic /tʃaʊdə/, but /tʃaʊda/, with an unreduced unstressed vowel. (In an Eastern N.E. accent, [a] appears in place of the usual [ɑ] in PALM, START, and BATH words.) This, I think, is what the non-standard spelling chowdah is supposed to represent.

Ben said,

April 3, 2011 @ 7:27 pm

Another good quote from the Times article is Tim Welsh saying “John really was trying to claim New England. He never could say he parked the car in the Harvard yard. He didn’t know what clam chowder really was. He had the red stuff, not the real clam chowder.”

Hermann G Burchard said,

April 3, 2011 @ 9:07 pm

@myl: the loss of syllable-final /r/ that took place in southeastern England during the 18th century

Hate to bring this up, but this was the time when the Electors of Hannova, "Hanover or Hannover (G.: Hannover, [haˈnoːfɐ]),"* non-rhotic, had inherited the English crown. Their speech became King's English..

– – –

*) Wikipedia

J. Goard said,

April 4, 2011 @ 12:34 am

A more complex theory of the same process can found in Michael Silverstein, "Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life", Language and Communication 23(3-4): 193-229, 2003.

Too bad that so many anthropologists still insist on making their academic language a kind of obstacle course toward the prize of understanding fairly simple concepts. The ideas in this paper are really great — I can easily see their extension to the discussion of EFL, perception of the dialects and national standards of various English-speaking counties. Just this morning, in fact, I was listening to some Koreans talk about a previous teacher and her "African English" (black South African), really trying to get at what they had been noticing, and noticing that people will notice…

vanya said,

April 4, 2011 @ 9:41 am

"There is considerable r-lessness in New Haven, for example, but it's conditioned by class and ethnicity too."

Really? My mother's Italian/Irish family is from Wallingford (the next town over), and I went to college in New Haven. I've never met a native of that region who speaks with an r-less accent. Which class and ethnicity are you thinking of?

Becky said,

April 4, 2011 @ 12:46 pm

I was born and raised in MA (outside of Worcester), now residing in CT for the last 2 years. I went to UMass Amherst and can definitely say that, in my experience, the only prevalence of the "Boston accent" heavy r-lessness comes when grow up directly in Boston or one of the towns directly outside of Boston (Saugus, Reading, etc).

The farther away from Boston proper you go geographically speaking, the less r-lessness you will hear in everyday speech of the locals.

This is true for Amherst, although many people from MA "play up" their r-lessness to a certain extent in certain situations.

As for CT, I have never encountered rampant r-lessness here (near Hartford) unless speaking with a Boston native.

Alexandra said,

April 4, 2011 @ 1:52 pm

@Becky:

I used to teach in Winchendon, MA, directly north of Worcester on the NH border, and there was plenty of r-lessness there, both among the teachers and the students. I came to think of the accent there as a "North-Central Massachusetts" accent. I don't know if there's really such a thing, but it sounded different from the regular, old Boston accent to me. It involved pronouncing "odd" as though it were spelled "ard" and Ayer (a nearby town) as /ea/.

Liz said,

April 4, 2011 @ 4:01 pm

the semi-glottal stop JMS noted in Northampton extends all the way west to Pittsfield, MA. As a native, I hadn't noticed until it was pointed out to me by a transplanted Texan. It creates interesting problems when I teach ESL as I find it unnatural to teach a sound for that stop, but the stop is impossible to teach to an ESL learner.

q said,

April 4, 2011 @ 4:49 pm

SteveT, that episode's the first thing that came to my mind as well, but specifically the court room scene:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZsoPlDBldSY

(skip to 1:55)

James Kabala said,

April 4, 2011 @ 10:14 pm

Like Becky and Alexandra, I am from Worcester County, which according to the map is apparently the land where four different accents meet. (My own hometown seems to be just barely within the Providence sector of the map, which is a bit of a surprise to me, although I live in Rhode Island now.) R-lessness was not unknown, but I don't think it was the dominant accent compared to eastern Massachusetts.

Rod Johnson said,

April 4, 2011 @ 11:30 pm

I thought I was pretty familiar with the manifold varieties of the medial consonant in words like "butter", but I'm at a loss to imagine what one "midway between glottal stop and flap" would be. Are there any recordings available?

JimG said,

April 7, 2011 @ 8:33 am

This discussion reminded me of "Bert and I." See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EPGf77t9hRA